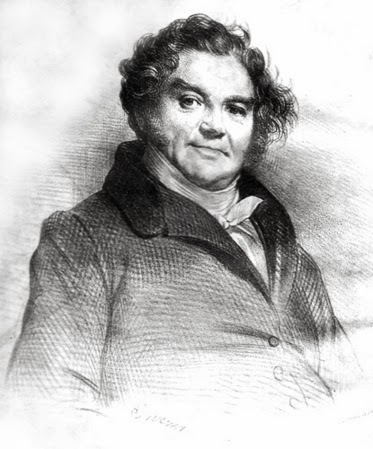

Eugène François Vidocq (1775 – 1857)

During the night of 23 to 24 July 1775, French criminal and criminalist Eugène Vidocq was born. Vidocq is considered the world’s first private detective and father of modern criminology. His life story inspired several writers, including Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac.

“I thought I could have remained an informer forever, so far from the thought of suspecting that I was a police agent. Even the door closers and the guards had no idea of the mission entrusted to me. I was almost worshipped by the thieves, the roughest bandits respected me, – even these people know a feeling that they call respect. I could always count on their devotion. They might have walked through fire for me.”

– Vidocq about his work as an informer: Hobo Life

The turbulent Youth of Eugene Vidocq

Vidocq was born as the third child of the master baker Nicolas Joseph François Vidocq (1744-1799) and his wife Henriette Françoise Vidocq (1744-1824, née Dion), in Arras, France. Little is known about Vidocq’s childhood. His father was educated and, as he was also a grain merchant, he was wealthy by the standards of the time. Surprisingly, the later criminalist had a pretty turbulent childhood and youth. He stole his parent’s silverware at the age of 13 and was sent to prison for 10 days. Just one year later, he stole more money from his parents, trying to get to America but again he was unsuccessful, wherefore he spent some time living as an entertainer on the streets of France. Vidocq later joined the French Army and fought several battles after France declared war to Austria in 1792. He became very unpopular after deserting several times and ‘hiding’ in new regiments wherefore he quit soon.

At age 18 he returned to Arras and made a reputation as a womanizer. As his seductions often ended in duels, he found himself on 9 January 1794 in Baudet’s prison, which he already knew, from which he was released on 21 January. On 8 August 1794, Vidocq, who had just turned 19, married Marie Anne Louise Chevalier, five days his senior, after she had pretended to be pregnant. The marriage was not a happy one from the start, and when Vidocq realised that his wife was cheating on him with Pierre Laurent Vallain, 14 years his senior, he swindled her out of some money and fled back to the army. It was not until 1805 that they met again on the occasion of their divorce.

The Armée Roulante

Even though Vidocq’s whole life sounds like a huge adventure, the years between 1795 and 1800 are known to be his “adventurer years”. He joined a special army called armée roulante. It consisted of a group of fake officers without regiments or even orders, who wore fake uniforms and promoted themselves. With the help of forged marching routes, ranks and uniforms they obtained shelter and rations, but remained far away from the battlefields. Vidocq alias Rousseau began as a sous lieutenant of the hunters, but gradually promoted himself to captain of the hussars. In this role he met a rich widow who took a liking to him. A superior of Vidocq’s made her believe that a young nobleman was fleeing from her. Shortly before the planned wedding, however, Vidocq got scruples and confessed. He then left the city with a generous gift of money from her.

A Foothold in the Underworld

On 2 March 1795 he reached Paris, where he was unable to gain a foothold in the underworld and lost much of his money because of a woman. He went back to the north and joined a group of Bohemian gypsies, which he in turn left for a woman – Francine Longuet – who shortly afterwards betrayed him with a soldier. He surprised and beat them both, and the soldier sued him. Vidocq was sentenced in September 1795 to three months in prison, which he was to serve in the Tour Saint-Pierre in Lille.

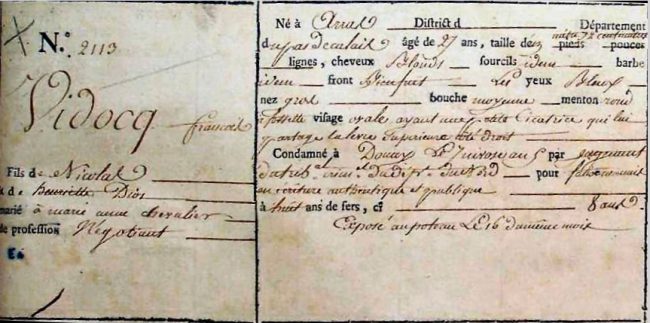

Document concerning the sentence of Eugène François Vidocq because of forgery to eight years of hard labor in the Bagno of Brest, 27th December 1796

The Bagno

Vidocq was 20 years old and quickly adapted to life in prison and the customs there. When his three months were up, he was not released. Three of his fellow prisoners had involved him in an escape and now he was suspected of forging documents and aiding and abetting escape. After a long delay, Vidocq who had always maintained his innocence, was trialed for falsification of documents in December 1796. Vidocq was found guilty and sentenced to eight years of hard labour in a bagno. Although there was no opportunity for escape on the way there, he was lucky in Bagno itself. Already in 1798 he managed to escape disguised as a sailor. He was picked up again on the way because of missing papers, but while his new identity details were being checked as Auguste Duval, he stole the habit of a nun in the prison hospital and escaped again with this disguise. In Cholet, he hired as a steersman and made his way to Paris, Arras, Brussels, Ancer and finally Rotterdam, where he was shanghaied by Dutchmen. After a brief career as a privateer, he was arrested again and taken to Douai, where he was identified as Vidocq. He was then transferred to the Bagno of Toulon, where he arrived in late August 1799. After a failed escape attempt, he finally escaped again in March 1800 with the help of a prostitute.

The Turn

After several further adventures, Vidocq was again captured in 1809 and offered the police to spy on other inmates in order to solve more crimes and to figure out their secret identities. The inmates trusted him and his mission was a great success. For a total of 21 months he interrogated his fellow prisoners and, through Annette, passed on his information on forged identities and previously unsolved crimes to the Paris police chief Jean Henry. In order not to cause distrust among his fellow prisoners, an “escape” was arranged, which took place on 25 March 1811. However, he was not free because he was now obliged to Henry. Therefore he continued his work for the Paris police as a secret agent. He used his contacts and the reputation of his name in the half- and underworld to gain trust, disguised himself as an escaped convict, dived into the network of helpers of the criminal scene and arrested, partly by his own hand, wanted criminals. His success rate was high.

The Sûrtée

“For political police means: an institution created by the desire to enrich oneself at the expense of the state, whose restlessness is constantly kept artificially in suspense. Political police is synonymous with the need to obtain secret money from the budget, with the need of certain officials to show themselves as indispensable by showing the state in alleged danger”.

– Vidocq: Hobo Life

At the end of 1811, Vidocq unofficially organized the Brigade de la Sûreté (Security Brigade). After the Ministry of Police recognized the value of civilian agents, the experiment officially became a security agency under the umbrella of the Paris police in October 1812. Vidocq was appointed its chief. Finally, on 17 December 1813, Napoleon Bonaparte signed a decree that made the brigade a state security police force, which from that day on was called the Sûreté nationale. The Sûreté initially had eight, then twelve, and finally 20 employees in 1823, and in the following year it was increased to 28 secret agents. In addition, there were eight people who worked in secret for the security authorities, but instead of a salary they received a licence for a gambling hall. Like Vidocq himself, the majority of his subordinates came from the criminal milieu. Some of them were recruited from the Bagnos for their work. Vidocq trained his agents personally, e.g. with regard to the right costume for an assignment. He still hunted down criminals himself. His memoirs contain numerous stories of how he outwitted criminals of all kinds, whether as an abandoned husband who had long since passed the prime of his years, or as a beggar. He did not even shrink from simulating his own death.

First Retirement

After 18 years of successfully leading the organisation, a few changes in the police’s headquarters occurred wherefore Vidocq decided to withdraw from his position in 1832. He then wrote his memoirs, in which he described the necessity and effectiveness of his security police and strictly opposed the political police.Several police men and journalists began to write about their adventures with the criminal and criminalist, wherefore numerous writings on Vidocq evolved. Several writers like Vidocq’s befriended Honoré de Balzac [10] also took a lot of inspiration for future works on detective stories and murder mysteries leaned on the life of the father of criminology. Vidocq, who was a rich man after his retirement, now became an entrepreneur. In Saint-Mandé, a town north of Paris, where he also married his cousin Fleuride Maniez in 1830, he set up a paper mill and hired mainly dismissed prisoners, both men and women. This constituted an outrageous scandal which led to disputes with society.

Second Retirement

Vidocq went bankrupt as a manufacturer in 1831. Police prefect Delavau and police chief Duplessis had to resign in his absence and abdicate Charles X during the July Revolution of 1830. After Vidocq provided valuable tips on how to detect a burglary, the new police prefect Henri Gisquet reinstated him as head of the Sûreté. But criticism of him and his organization grew. In 1832, his troops allegedly took a tough stance against riots that broke out during a cholera epidemic at the funeral of General Jean Maximilien Lamarque and endangered the throne of the “Citizen King” Louis-Philippe. In addition, Vidocq was suspected of having initiated the theft, the investigation of which led to his reinstatement, in order to prove his indispensability. Finally, defense attorneys increasingly claimed that he and his agents were untrustworthy as eyewitnesses because of their past as criminals. Vidocq’s position became untenable. On November 15, 1832, he resigned on the pretext of his wife’s illness. On the same day the Sûreté was dissolved and newly founded. Agents with criminal records were no longer allowed.

Death and Legacy

Vidocq was briefly imprisoned for the last time in 1849, but the charge of fraud was dropped. He withdrew more and more into private life and mostly took on only small jobs. In the last years of his life he suffered massive pain from an arm that was broken in fights and never really healed. Vidocq died on 11 May 1857 at the age of 82 in the presence of his doctor, his lawyer and a priest. Eugene Vidocq revolutionized criminology with new methods concerning the handling with criminals psychologically, concerning secret investigations and forensic methods using the latest achievements in science and even patenting a few himself.

Criminology: A Very Short Introduction | Tim Newburn | Talks at Google, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Vidocq Society

- [2] Article on Vidocq at Strand Magazine

- [3] Vidocq Biography

- [4] Vidocq – Du Bagne à la Police de Sûreté (French)

- [5] Works by or about Eugène François Vidocq at Internet Archive

- [6] Edwards, Samuel (1977). The Vidocq Dossier: The Story of the World’s First Detective (1st ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- [7] Mémoires de Vidocq, chef de la police de Sûreté, jusqu’en 1827, ghost-written autobiography, 1828

- [8] Eugene Vidocq at Wikidata

- [9] Criminology: A Very Short Introduction | Tim Newburn | Talks at Google, 2019, Talks at Google @ youtube

- [10] Honoré de Balzac and the Comédie Humaine, SciHi Blog

- [11] Timeline of Private Investigators and Detectives, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Eugène-François Vidocq, The Ex-Convict Who Revolutionized Police Work – Click That Shtick

Pingback: The Swashbuckling Tale Of Eugène-François Vidocq, The Career Criminal Who Revolutionized The French Police - The Real Facts

Pingback: The Swashbuckling Tale Of Eugène-François Vidocq, The Career Criminal Who Revolutionized The French Police - E.Y.E

Pingback: Eugène-François Vidocq, The Ex-Convict Who Revolutionized Police Work - Daily Tech Facts

Pingback: The Noteworthy Life of Eugène-François Vidocq, Inventor of Neatly-liked Detective Work - Jirnal