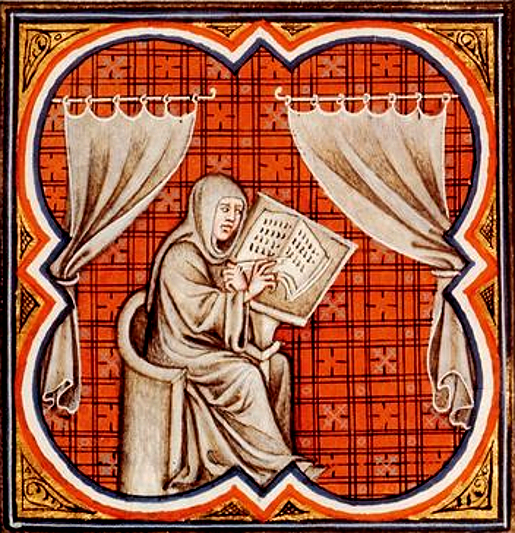

Einhard (770 – 840) in the Grandes Chroniques de France, Paris, BnF, lat. 2813, fol. 85v A, 14th century (1375-1380).

On March 14, 840, Frankish scholar and courtier Einhard passed away. A dedicated servant of Charlemagne [1] and his son Louis the Pious, Einhard’s is best known for “Vita Karoli Magni“, a biography of Charlemagne, one of the most precious literary bequests of the early Middle Ages.

Einhard’s Family Background and Education

Einhard, who came from a noble East Franconian family in the eastern German-speaking part of the Frankish Kingdom, was initially educated in the monastery of Fulda. He is documented as having written documents there between 788 and 791. In 794, Abbot Baugulf of Fulda sent him to the court school to further perfect his education, where he became a student of Alcuin and soon belonged to the inner circle around Charlemagne.[2]

On Charlemagne’s Court

Einhard oversaw the construction of many of Charlemagne’s buildings, such as the bridge at Mainz, the palaces at Ingelheim and Aachen, and the Palatine Chapel at Aachen. He also supervised the court workshops. It is unclear to what extent he himself was active in the arts or crafts, but he seems to have done at least conceptual work. What has not survived is the so-called Einhard Arch, a triumphant arch-shaped reliquary that he commissioned after 815 as a lay abbot for his abbey in Maastricht. It served as a pedestal for a cross and exhibits stylistic touches with the bronze grids of St. Mary’s Church in Aachen.

Einhard as scribe. Manuscript depiction from 1050

Rome and Charlemagne’s Heirs

His pupil Brun Candidus of Fulda was active as a biographer as well as a monumental and book painter. Einhard was Charlemagne’s companion on all his journeys, went to Rome as Charlemagne’s envoy in 806, and in 813 his advice is said to have persuaded Charlemagne to appoint his son Louis emperor. The latter also trusted Einhard and gave him as advisor to his son Lothar I in 817. In the struggles of the sons against their father, Einhard, as a representative of the idea of imperial unity, strove for a peaceful solution to the conflicts. He founded an abbey near Michelstadt in the Odenwald, the Einhard Basilica in Steinbach. There is an interesting story related to this. Einhard sent a servant, Ratleic, to Rome with an end to find relics for the new abbey. Once in Rome, Ratleic robbed a catacomb of the bones of the Martyrs Marcellinus and Peter and had them translated to Michelstadt. Once there, the relics made it known they were unhappy with their new tomb and thus had to be moved again to Mulinheim. Once established there, they proved to be miracle workers. In the course of time Muhlinheim received the name Seligenstadt because of the relics of the abbey. Einhard seems never to have been a clergyman, but, according to the custom of the time, led the above-mentioned monasteries and convents as a lay abbot.

Imma, his Wife

In 836 his wife Imma died, who, contrary to the ineradicable legends that make her a daughter of Charlemagne against all historical probability on the basis of the latest tradition, probably came from the count family of Geroldingen, which was located in the Middle Rhine region and to which Imma, the mother of Hildegard, Charlemagne’s wife, also belonged. An extensive relationship of Einhard’s wife with Hildegard and thus also with Louis the Pious seems therefore not improbable, which would sufficiently explain her being singled out by name in the deed of donation for Michelstadt of 815.

Vita Karoli Magni and other Works

Of the four works of Einhard still known today, the biography of Charlemagne, the Vita Karoli Magni, is the most important. Einhard wrote this only biography of Emperor Charlemagne by a contemporary, following Suetonius’ ancient biographies of emperors, but without slavishly following their model closely. Another important work is the Translatio et Miracula SS Marcellini et Petri, an account of the transfer of the relics of two saints from Rome to Seligenstadt, which he arranged, with the miracle narratives common to translation accounts. Finally, there is the short theological writing De adoranda cruce and a selection from the Psalms prepared for prayer purposes. In addition, a larger collection of Einhard’s letters (a total of 71, 58 of which with Einhard as the author) has survived. It has been debated whether Einhard could be the author of the Aachen Epic of Charlemagne, which has survived anonymously.

According to recent findings, Einhard was not involved in the writing of the so-called Annales Fuldenses (Fulda Annals) and the Annales regni Francorum (Annals of the Frankish Empire, Imperial Annals), which were earlier attributed to him (“Annales qui dicuntur Einhardi”, “Annales Einhardi”).

Death and Local Lore

Einhard died in Seligenstadt on March 14, 840. His epitaph, in which only his artistic works and the translation of St. Marcellinus and St. Peter are mentioned as merits, but not his literary work, was written by the Fulda abbot Hrabanus Maurus [3]. Local lore from Seligenstadt portrays Einhard as the lover of Imma, one of Charlemagne’s daughters, and has the couple elope from court. Charlemagne found them at Seligenstadt and forgave them. This account is used to explain the name “Seligenstadt” by folk etymology. The legend is handed down in the Chronicon laurishamense, the chronicle of the monastery of Lorsch, written in the 12th century and can also be found in the German sagas of the Brothers Grimm, among others.[13]

Einhard and his wife were originally buried in one sarcophagus in the choir of the church in Seligenstadt, but in 1810 the sarcophagus was presented by the Grand Duke of Hesse to the count of Erbach, who claims descent from Einhard as the husband of Imma, the reputed daughter of Charlemagne. The count put it in the famous chapel of his castle at Erbach in the Odenwald.

Paul H. Freedman, 20. The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000: Intellectuals and the Court of Charlemagne, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Charlemagne and the Birth of the European Idea, SciHi Blog

- [2] Alcuin of York – Architect of the Carolingian Renaissance, SciHi Blog

- [3] The Encyclopaedia of Rabanus Maurus, SciHi Blog

- [4] Smith, Julia (March 2003). “Einhard”. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society: 55–77

- [5] Noble, Thomas F.X. (2009). Charlemagne and Louis the Pious: Lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus, Thegan, and the Astronomer. Penn State Press.

- [6] Works by or about Einhard at Internet Archive

- [7] Vita Karoli Magni—Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne, Latin text at The Latin Library

- [8] The Einhard Way from Michelstadt to Seligenstadt

- [9] Wilhelm Wattenbach: Einhard. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 5, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1877, S. 759

- [10] Heinz Löwe: Einhard. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0, S. 396 f.

- [11] Einhard at Wikidata

- [12] Paul H. Freedman, 20. The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000: Intellectuals and the Court of Charlemagne, The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000 (HIST 210), Yale Courses @ youtube

- [13] Eginhart und Emma. In: Brüder Grimm (Hrsg.): Deutsche Sagen, Band 2. Nicolai, Berlin 1818, S. 125–128

- [14] Timeline of Frankish Historians, via DBpedia and Wikidata