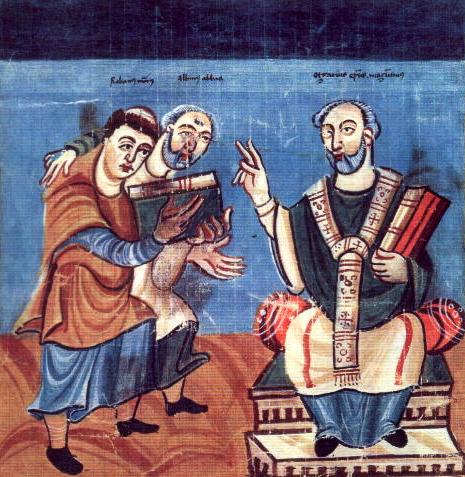

The young Hrabanus Maurus (left), supported by his teacher Alkuin, the abbot of the monastery of St. Martin of Tours (centre), presents his work De laudibus sanctae crucis to St. Martin, Archbishop of Tours, later mistakenly called Archbishop Otgar of Mainz. Representation in a manuscript from Fulda around 830/40

On February 4, 856, Frankish Benedictine monk, theologian, poet, encyclopedist and military writer Rabanus Maurus Magnentius passed away. He was the author of the encyclopaedia De rerum naturis (“On the Natures of Things“). He also wrote treatises on education and grammar and commentaries on the Bible. He was one of the most prominent teachers and writers of the Carolingian age, and was called “Praeceptor Germaniae,” or “the teacher of Germany.”

How Rabanus became Rabanus Maurus

Rabanus was born around 780, according to Eckhard Freise only “about 783”, as son of noble parents in Mainz, an old Roman city in Francia located at the confluence of the rivers Rhine and Main. Already as a child at the age of eight years at the most, he was handed over by his parents as puer oblatus into the care of the monastery of Fulda and from 788 he attended the school of the then flourishing Benedictine monastery of Fulda for religious and scientific education, but not yet at the peak of the fame he later achieved under his own leadership. After completing his education he was able to shine as a scholar at the court of Charlemagne at an early age.[1] Here he was encouraged by Alcuin,[2] the head of the Imperial Court School in Aachen. Alcuin called him “Maurus”, as the founder of the order, Benedict, had also called his favourite pupil. When Alcuin entered the canon monastery of Saint-Martin de Tours, Rabanus followed him to study the Bible, liturgy and law.

Teacher in the Fulda Monastery

In 801 he was ordained a deacon. Returning to Fulda in 803 even before Alcuin’s death he was entrusted with the principal charge of the abbey school, which under his direction became one of the most preeminent centers of scholarship and book production in Europe, and sent forth such pupils as Walafrid Strabo, Servatus Lupus of Ferrières, and Otfrid of Weissenburg. In 814 he was ordained priest. It was probably at this period that he compiled his excerpt from the grammar of Priscian, a popular textbook during the Middle Ages. Priscianus Caesariensis, commonly known as Priscian, was a Latin grammarian and the author of the Institutes of Grammar which was the standard textbook for the study of Latin during the Middle Ages. It also provided the raw material for the field of speculative grammar.

The Writings of Rabanus Maurus

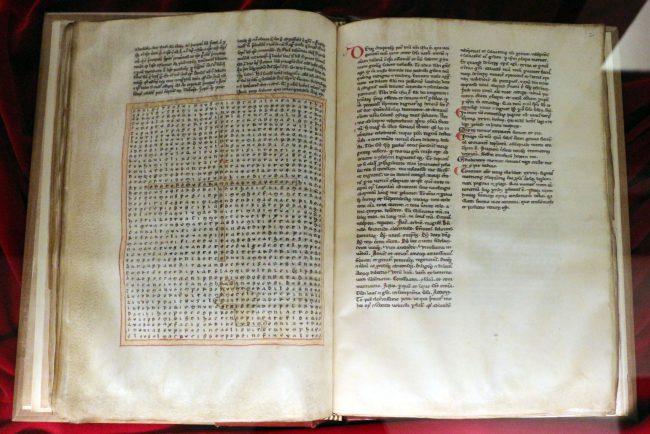

During his time as head of the monastery school (until 822) Rrabanus wrote writings of great thematic diversity. They are divided into biblical commentaries, letters, poems, hymns, sermons, doctrinal writings, dogmatic (including liturgical), canonical and hagiographical writings, as well as writings on political issues of the epoch. The most famous work is the figurative poetry cycle De laudibus sanctae crucis (“In Praise of the Holy Cross“, completed in 814), an opus geminum. It is still preserved today in copies that were probably made directly under the supervision of Rabanus; the most important copy with the author’s own entries is kept in the Vatican Library. His activity as head of the school is testified by his three-volume work De institutione clericorum (“On the formation of the clergy“), published in 819. This work was later followed by De sacris ordinibus and De ecclesiastica disciplina.

De laudibus S. Crucis, 13. Jhdt., Florenz, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 31 sin. 9, fol. 31v

Most of the work consists of Bible commentaries that cover almost the entire Old and New Testament. Apart from De laudibus sanctae crucis, Rabanus Maurus wrote numerous other metrical and accent rhythmic poems, some in rare verses, including numerous altartituli as well as epitaphs, including one for the tomb of Saint Boniface, whose stela with relief of the saint, a cross on the back and the inscription sancta crux nos salva (Holy Cross, save us) has been preserved in Mainz (so-called priest’s stone). Letters have also survived in greater numbers. Although no texts in the vernacular have survived from Hrabanus, he is regarded as a promoter of the effort to write in the vernacular for the purposes of school and pastoral care in Fulda.

The Encyclopaedy – De Rerum Naturis

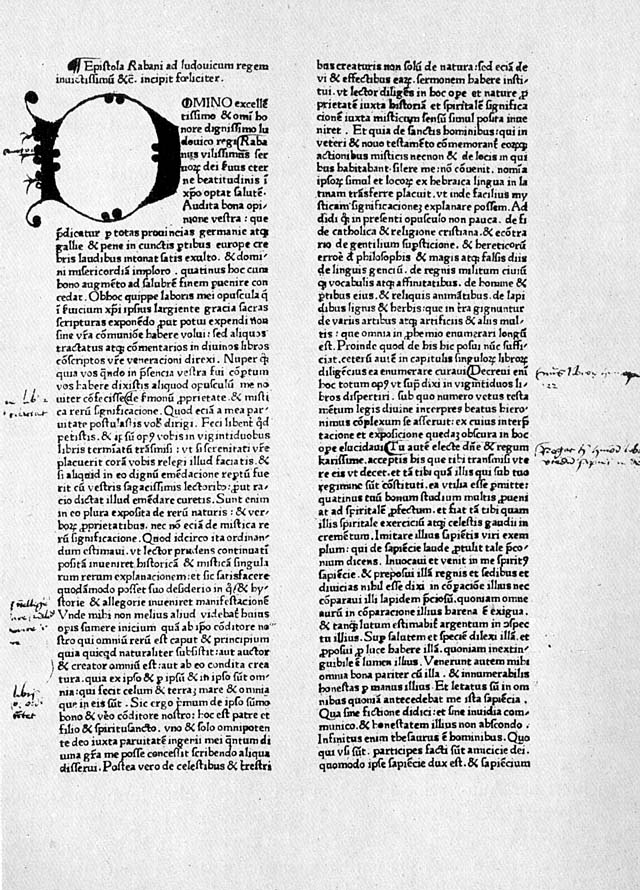

Apart from De Laudibus sanctae crucis, probably Rabanus’ most successful work was his encyclopaedia De rerum naturis in 22 books, which, based on the Etymologiae of Isidor of Seville, places man (with his anatomy and diseases), the stars and the plant kingdom in a cosmic context. Accordingly, the structure of the work is not based, like the Isidors, on the system of the septem artes liberales, but takes its starting point from the Supreme Good, the Creator God, and treats things in descending order according to their position within the hierarchy of the cosmic order. Their extensive handwritten tradition extends from the 9th to the 15th century and includes several illustrated copies, the oldest of which is the famous 11th century copy from Monte Cassino. The first incunabulum print by Adolf Rusch appeared in Strasbourg shortly before 1467. The work served primarily as an aid to Bible exegesis. Whether the illustrations can be traced back to Rabanus is disputed, but not unlikely. According to a communication from the diocese of Mainz, the Mainz scholar Franz Stephen Pelgen discovered another manuscript fragment of the 9th century from this work in the Martinus Library in Mainz at the end of June 2011.

Rabanus Maurus, De rerum naturis (after 842). Early print with handwritten marginalia.

Abbot of the Fulda Monastery

On 15 June 822 he became abbot of the monastery of Fulda for twenty years, which at that time, including the secondary monasteries, housed a total of over 600 monks. He enlarged the monastery library and developed the monastery school into one of the most renowned in the Frankish Empire. He significantly increased the church and relic treasures. He had the scattered property of the monastery recorded in a large collection of documents, an eight-volume so-called Chartular, and organized the administration of property through a hierarchical system of front courts and upper front courts. As a resolute advocate of the idea of imperial unity, he was a follower first of Emperor Louis the Pious, after whose death he was then succeeded by Emperor Lothar I, but not by Louis the German, to whose domain Fulda belonged. When he was drawn into the disputes between Louis the Pious and his sons, he resigned from his office as abbot in 842 and retired as a scholar to the provostry of St. Peter on Petersberg.

Later Years

Despite the differences of opinion, Ludwig elevated him in 847, already 67 years old, after a debate in Rasdorf, a branch of the monastery of Fulda, to archbishop of Mainz. On 16 June of the same year, Rabanus took up his office as head pastor of the largest church province in the East Franconian Empire. Shortly after assuming his office, he convened a first synod, at which bishops, choir bishops (a preform of the present auxiliary bishop) and abbots in the Mainz Abbey of St. Alban discussed the strengthening of faith and discipline. The preachers were encouraged to preach sermons that were understandable to the common people. According to tradition, Rabanus Maurus died on 4 February 856 in Winkel in the Rheingau region and was buried in St. Alban Abbey outside Mainz. He was soon venerated as a saint.According to Alban Butler’s Lives of the Saints, Rabanus ate no meat and drank no wine.

Significance and Legacy

When the so-called Carolingian Renaissance got stuck in its infancy due to the divisions of Charlemagne’s empire and the emerging Eastern France was seeking its spiritual foundations, Hrabanus Maurus acted as a collector and mediator of the entire philosophical, theological and scientific knowledge of his time. The abundance of his writings on all fields of knowledge and the large number of his important students earned him the honorary title of “First Teacher of Germania” (primus praeceptor Germaniae) in the early 19th century, the justification of which, however, is questioned by more recent historical research. In any case, it is certain that he was the first scholar from the German-speaking area to comment on almost the entire Bible and to present the entire knowledge of his epoch in his writings, and that among his numerous students, who were themselves literarily productive, were important representatives of the Carolingian Renaissance and, with Gottschalk and Walahfrid Strabo, the two probably most important poets of the ninth century. His influence extended far beyond the German-speaking area.

Paul Freedman, 20. The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000: Intellectuals and the Court of Charlemagne, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Charlemagne and the Birth of the European Idea, SciHi Blog

- [2] Alcuin of York – Architect of the Carolingian Renaissance, SciHi Blog

- [3] De rerum naturis: (lat.) in Bibliotheca Augustana

- [4] Works by and about Rabanus Maurus in the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library)

- [5] Works written by or about Rabanus Maurus at Wikisource

- [6] Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- [7] Rabanus Maurus at Wikidata

- [8] Paul Freedman, 20. The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000: Intellectuals and the Court of Charlemagne, YaleCourses @ youtube

- [9] Timeline of People from the Carolingian Empire, via DBpedia and Wikidata