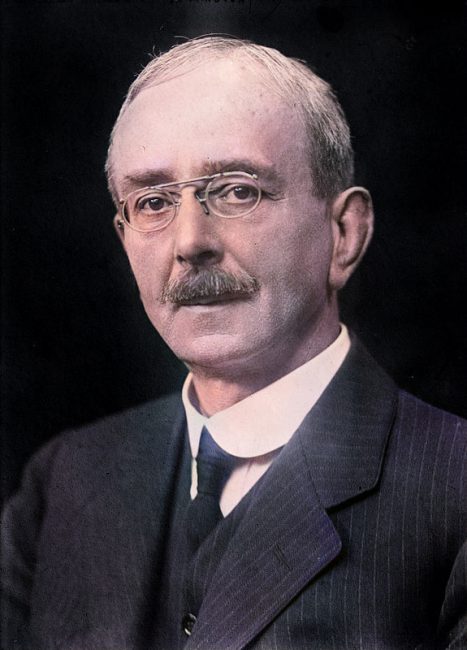

Charles Scott Sherrington (1857 – 1952)

On November 27, 1857, English neurophysiologist and Nobel Laureate Sir Charles Scott Sherrington was born. Sherrington received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Edgar Adrian in 1932 for their work on the functions of neurons. Prior to the work of Sherrington and Adrian, it was widely accepted that reflexes occurred as isolated activity within a reflex arc. Sherrington received the prize for showing that reflexes require integrated activation and demonstrated reciprocal innervation of muscles (Sherrington’s law).

“The brain is a mystery; it has been and still will be. How does the brain produce thoughts? That is the central question and we have still no answer to it.”

– Charles Scott Sherrington, as quoted in [11]

Charles Scott Sherrington – Early Years

Charles Scott Sherrington was born in Islington, London, England, on 27 November 1857, one of four sons of James Norton Sherrington, a country doctor working near Yarmouth (Isle of Wight), and his wife Anne Brookes Thurtell. It is believed that Sherrington’s academic sense of wonder was shaped by the intellectuals that frequented his home regularly. He entered Ipswich School in 1871 and was highly inspired by his teacher Thomas Ashe, a famous English poet. Through Ashe, Sherrington developed a love of classics, mainly Latin and Greek, and a desire to travel. Sherrington began to study with the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Sherrington elected to enroll at St Thomas’ Hospital in September 1876 as a “perpetual pupil”, where his studies were intertwined with studies at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. Physiology was Sherrington’s chosen major at Cambridge. There, he studied under the “father of British physiology,” Sir Michael Foster. In October 1879, Sherrington entered Cambridge as a non-collegiate student. The following year he entered Gonville and Caius College. Walter Holbrook Gaskell, one of Sherrington’s tutors, informed him in November 1881 that he had earned the highest marks for his year in botany, human anatomy, and physiology. He was second in zoology, and highest overall. Charles Scott Sherrington earned his Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons on 4 August 1884 and one year later he obtained a First Class in the Natural Science Tripos with the mark of distinction and earned the degree of M.B., Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery from Cambridge. In 1886, Sherrington added the title of L.R.C.P., Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians.

Neurophysiology

Sherrington’s interest in the nervous system was aroused at the 17th International Congress of Medicine in London in 1881 when the physiologist Friedrich Leopold Goltz of Strasbourg demonstrated his debarked dogs. Sherrington asked Goltz to allow him to examine the rest of the nervous system of his debarked animals. Goltz gave him permission to do so; with these investigations, which he carried out together with the professor of physiology, John Newport Langley, in Cambridge, his career as a neurophysiologist began. David Ferrier, who became a hero of Sherrington’s, disagreed with Goltz’s hypotheses. Ferrier maintained that there was localization of function in the brain. Ferrier’s strongest evidence was a monkey who suffered from hemiplegia, paralysis affecting one side of the body only, after a cerebral lesion. A committee was created to investigate the matter on a dog and monkey. The right hemisphere of the dog was delivered to Cambridge for examination. Sherrington performed a histological examination of the hemisphere, acting as a junior colleague to Langley. In 1884, Langley and Sherrington reported on their findings in a paper. The paper was the first for Sherrington.

Research on the Continent

During the period of his education following his state examination at Cambridge University, which he completed in 1885, Sherrington spent long periods in Germany. In Berlin, he attended the lectures of Hermann von Helmholtz,[6] for whom he felt deep admiration. On the other hand, he considered Emil Heinrich du Bois-Reymond a most fascinating lecturer.Sherrington traveled to Rudolf Virchow [7] in Berlin to work on cholera. Virchow later on sent Sherrington to Robert Koch for a six weeks’ course in technique. Sherrington ended up staying with Koch for a year to do research in bacteriology. Under these two, Sherrington parted with a good foundation in physiology, morphology, histology, and pathology.

First Appointment

His training on the Continent was followed by his first appointment as lecturer in physiology at St. Thomas Hospital; later he was appointed professor and medical director of the Brown Institute (1891). Sherrington remained here for four years. Some of his best work on the nervous system was based on research at the Brown Institute, including his monograph on peripheral distribution of fibers from posterior spinal cord roots. His studies on the reciprocal innervation of antagonistic muscles also began during this period.

Sherrington’s Law of Reciprocal Innervation

Charles Scott Sherrington’s first job of full-professorship came with his appointment as Holt Professor of Physiology at Liverpool in 1895. He found that reflexes must be considered integrated activities of the total organism, not just the result of activities of the so-called reflex-arcs, a concept then generally accepted. Sherrington continued his work on reflexes and reciprocal innervation. His papers on the subject were synthesized into the Croonian lecture of 1897. Like many young scientists, he was exploited to write a special section for Michael Foster‘s textbook of physiology. In this book, he introduced the term synapse (Greek συναψις = connection) to neurology, which was immediately adopted and has been in general use ever since. Further he showed that muscle excitation was inversely proportional to the inhibition of an opposing group of muscles. Speaking of the excitation-inhibition relationship, Sherrington said “desistence from action may be as truly active as is the taking of action.” In 1906 his book on “The Integrative Activity of the Nervous System” was published, based on the Silliman lectures. This work of Sherrington was a turning point in human experimental physiology, because it explained for the first time John Hughlings Jackson‘s concepts of the origin of function and introduced many new terms;[8] they are used today by neurophysiologists all over the world (e.g. proprioception and nociceptors).

Later Years

Oxford offered Sherrington the Waynflete Chair of Physiology in 1813. Sherrington’s teachings at Oxford were interrupted by World War I. During the war, he laboured at a shell factory to support the war and to study fatigue in general, but specifically industrial fatigue. In March 1916, Sherrington fought for women to be admitted to the medical school at Oxford. Charles Sherrington retired from Oxford in the year of 1936. Sherrington was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1932 for his research on reflex action and regenerative processes in nerve tissue. In old age, he philosophized about the meaning of his life’s work. In a 1933 address to Cambridge University on “The brain and its mechanism,” he dwelt at some length on the subject of “the brain as an organ of the mind.” He concluded that no clear relationship between body and soul could be demonstrated.

Charles Scott Sherrington died on 4 March 1952 in Eastbourne, Sussex, at age 94.

Chris Whitty, Infections and the Nerves, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Charles Scott Sherrington Biography

- [2] Charles Scott Sherrington at Famous Scientists

- [3] Gibson, W.C. (2001). Twentieth Century Neurology, The British Contribution – first chapter. Imperial College Press.

- [4] “Sir Charles Scott Sherrington’s Histology Demonstration Slides”. History of Medical Sciences. University of Oxford.

- [5] Liddell, E. G. T. (1952). “Charles Scott Sherrington. 1857-1952”. Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 8 (21): 241–270.

- [6] Hermann von Helmholtz – Physiologist and Physicist, SciHi Blog

- [7] Rudolf Virchow – the Father of Modern Pathology, SciHi Blog

- [8] John Hughlings Jackson and his studies of Epilepsy, SciHi Blog

- [9] Chris Whitty, Infections and the Nerves, Gresham College @ youtube

- [10] Charles Scott Sherrington at Wikidata

- [11] The Human Brain — Three Pounds of Mystery, in The Watchtower magazine (15 July 1978)

- [12] Timeline for Charles Scott Sherrington via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #15 | Whewell's Ghost