Charles de l’Écluse (lat. Carolus Clusius, 1526-1609)

On April 4, 1609, Flemish doctor and pioneering botanist Charles de l’Écluse, L’Escluse, or with his Latin name Carolus Clusius passed away. He is considered perhaps the most influential of all 16th-century scientific horticulturists. He travelled and collected botanical information throughout Europe, and introduced new plants from outside Europe. In the history of gardening he is remembered not only for his scholarship but also for laying the foundations of Dutch tulip breeding and the bulb industry today.

Charles de l’Ecluse – Early Years

Charles de l’Ecluse was born in Arras, in the Province of Artois in Northern France on 19 February, 1526, to his father Michel de l’Ecluse, Seigneur de Watènes, a nobleman who served as councillor at the provincial court of Artois. Charles went to university at Louvain, where he studied law under Gabriel Mudaeus. In 1546 he entered the Collegium Trilingue in Louvain, and subsequently in 1548, he was at Marburg to study law, but his protestant conviction appears to have led him to Wittenburg in 1549 where he studied with the reformer Melanchthon.[2]

Botanical Research

On the advice of Melanchthon he changed his subject to medicine and botany, and in 1551 he returned to France to study at Montpellier under the botanical professor Guillaume Rondelet.[5] It was the time when botany was becoming a discipline in its own right and no longer considered a branch of medicine, the plants of interest only for their medicinal or culinary properties. D’Ècluse was one of the first in northern Europe to recognize plants for their own sake, valuing their beauty as well as their use.[1] During his years of study he acquired no less than eight languages as well an extensive knowledge of a wide variety of subjects. His first publication was a French translation of Rembert Dodoens’ herbal, published in Antwerp in 1557.[6] In the 1560s he stayed in the Southern Netherlands and was involved in the production of the splendid series of ‘libri picturati’. His Antidotarium sive de exacta componendorum miscendorumque medicamentorum ratione (1561) initiated his fruitful collaboration with the renowned Plantin printing press at Antwerp, which permitted him to issue late-breaking discoveries in natural history and to ornament his texts with elaborate engravings.

The Imperial Medical Garden

In 1573 Charles de l’Écluse was appointed prefect of the imperial medical garden in Vienna by Emperor Maximilian II and made Gentleman of the Imperial Chamber, but he was discharged from the imperial court shortly after the accession of Rudolf II in 1576. Clusius, as he latinized his name, was also among the first to study the flora of Austria, under the auspices of Maximilian II. He was the first botanist to climb the Ötscher and the Schneeberg in Lower Austria, which was also the first documented ascent of the latter. His contribution to the study of alpine plants has led to many of them being named in his honor.

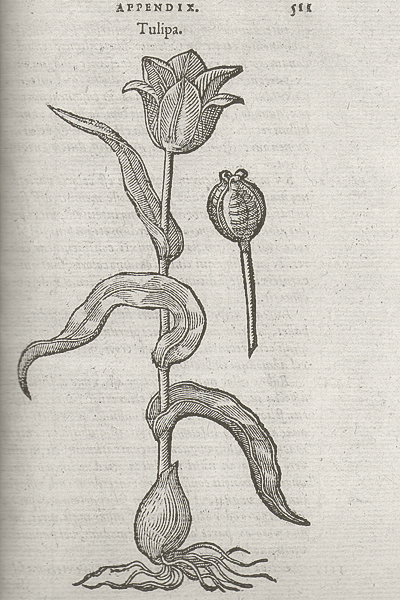

Woodcut of the tulip is from Clusius’ Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia (1576)

Tulips and Potatos

This high patronage enabled him to travel all over Europe, collecting information for his botanical studies and introducing a range of new plants from outside Europe, such as the tulip and the potato. In 1576 his Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia (Spanish Flora) was published at Antwerp, followed in 1583 by his description of the plants of Austria and neighbouring regions.[2] In the autumn of 1593, Clusius was persuaded to accept a position at the University of Leiden as honorary professor of botany where he supervised the establishment of one of the earliest formal botanical gardens of Europe, the Hortus Academicus, bringing with him his own collection of tulip bulbs which he planted that year. The next spring, in 1594, the first tulips flowered in the northern Netherlands.[1]

The Arrival of Tulips in the Netherlands

Tulips, a native of western Asia, Turkey the Balkans and Greece were first brought to Constantinople by the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire where the tulip became the favourite flower in Ottoman gardens and its image was extensively used to decorate tiles and textiles. Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, the Holy Roman Empire’s ambassador to the Court of Sulieman the Magnificent between 1555-1562, is credited with spreading the fame of tulips to Europe although his famous letters describing them were not actually published until 1580s.[3] Clusius apparently received some tulip bulbs and seeds from Busbecq when he was in Vienna establishing a botanic garden for the Emperor Maximilian II. With the arrival of the tulips in the Netherlands, Clusius unwillingly had created a new fashion hype in the Netherlands. Clusius wrote a colleague complaining that the exclusive world of the connoisseur was being cheapened by too many people becoming involved in the flower trade. Everyone was asking for flowers and, instead of free exchange among a like-minded collectors, they now were being bought and sold. Refusing to give his bulbs to those he suspected of wanting them only to resell for a profit, most were stolen, usually by a servant or gardener.[1]

The Tulip Industry

In the history of gardening he is remembered not only for his scholarship but also for his observations on tulips “breaking” — a phenomenon discovered in the late 19th century to be due to a virus — causing the many different flamed and feathered varieties, which led to the speculative tulip mania of the 1630s. Clusius laid the foundations of Dutch tulip breeding and the bulb industry today.

Charles de l’Ecluse died in Leiden in the Netherlands in 1609, at the age of 83.

The History of the Tulip | Short Animation, [9]

- [1] Carolus Clusius at University of Chicago

- [2] Charles de L’Ècluse at SummaGallicana.it

- [3] Carolus Clusius at Botany at the Edward Worth Library

- [4] The Clusius Project at the University of Leyden

- [5] Guillaume Rondelet and the Aquatic Life, SciHi blog

- [6] Rembert Dodoens and the Love for Botanical Science, SciHi Blog

- [7] The Burst of the Tulip Bubble, SciHi Blog

- [8] Charles de L’ècluse at Wikidata

- [9] The History of the Tulip | Short Animation, Short film for Tulip Museum Amsterdam, Animation: Steggink & Steggink, Voice Over: Adam Fields, Director: Stephane Kaas, Text: Durkje van der Wal, Stephane Kaas @ youtube

- [10] Ommen, Kasper van, ed. (2009). “The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius (1526-1609): Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009”

- [11] “Charles Clusius (1526-1609) Rariorum plantarum historia 1601”. Royal Collection Trust.

- [12] Timeline for Charles de L’Ècluse via Wikidata

What’s up, I read your new stuff daily. Your writing style is awesome,

keep it up!