Anders Johan Lexell (1740 – 1784)

On December 24, 1740, Finnish-Swedish astronomer, mathematician, and physicist Anders Johan Lexell was born. Lexell made important discoveries in polygonometry and celestial mechanics; the latter led to a comet named in his honour. La Grande Encyclopédie states that he was the prominent mathematician of his time who contributed to spherical trigonometry with new and interesting solutions, which he took as a basis for his research of comet and planet motion. His name was given to a theorem of spherical triangles.

“I like Lexell’s works, they are profound and interesting, and the value of them is increased even more because of his modesty, which adorns great men”

– Johann Albert Euler

Youth and Education

Anders Johan Lexell was born in Åbo (now Turku, Finland) as the son of Johan Lexell, an administrator, and Madeleine-Catherine Björkegren. Lexell studied at the University of Åbo and earned his Doctor of Philosophy degree with a dissertation on Aphorismi mathematico-physici under the supervision of Jakob Gadolin. Later on, Lexell moved to Uppsala and began working at Uppsala University as a mathematics lecturer. In 1766, Lexell became professor of mathematics at the Uppsala Nautical School.

Going to Russia

During the 1760s, Catherine the Great ascended to the Russian throne and started the politics of enlightened absolutism. As she was aware of the importance of science, she ordered to offer Leonhard Euler [4] to “state his conditions, as soon as he moves to St. Petersburg without delay“. After his return to Russia, Leonard Euler suggested that the director of the Russian Academy of Science should invite mathematics professor Anders Johan Lexell to study mathematics and its application to astronomy, especially spherical geometry.

Lexell intended to become a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. In order to be admitted he successfully wrote a paper on integral calculus titled Methodus integrandi nonnulis aequationum exemplis illustrata. Lexell moved to St. Petersburg and first became familiar with the astronomical instruments that would be used in the observations of the transit of Venus. He participated in observing the 1769 transit at St. Petersburg together with Christian Mayer.

The travelling Professor

In 1775, Anders Johan Lexell was appointed to a chair of the mathematics department at the University of Åbo with permission to stay at St. Petersburg for another three years to finish his work there. His permission was later prolonged for two more years. During the 1780s, Lexell departed St. Petersburg for a study trip. He arrived in Berlin, and traveled to Potsdam, seeking in vain for an audience with King Frederick II. He then traveled to Bavaria visiting Leipzig, Göttingen, and Mannheim on the way. Later, Lexell traveled to Strasbourg and then to Paris, where he spent the winter. In 1781, he moved to London and after a few months, he left for Belgium and the Netherlands, returning to Germany in fall. Lexell further traveled to Sweden and returned to St. Peterburg in December. During his trip, Anders Lexell wrote numerous letters to Johann Euler with descriptions of places and people he met.

Lexell’s Contributions to Celestial Mechanics

Anders Johan Lexell is best known for his efforts in the field of celestial mechanics. His first work at the Russian Academy of Sciences was to analyse data collected from the observation of the 1769 transit of Venus. He further calculated the parallax of the Sun, and published his work in 1772. During the next decade, he computed the orbits of all the newly discovered comets, among them the comet which Charles Messier discovered in 1770.[5] Lexell computed its orbit, showed that the comet had had a much larger perihelion before the encounter with Jupiter in 1767 and predicted that after encountering Jupiter again in 1779 it would be altogether expelled from the inner Solar System. This comet was later named Lexell’s Comet. Lexell also helped Euler to develop his theory of the moon and was co-author of Euler’s “Theoria motuum Lunae” published in 1772.

Further, Anders Lexell calculated the orbit of Uranus and he proved that it was a planet, and not a comet. During his time in Europe, Lexell already made preliminary computations and after returning to Russia, he was able to make more precise calculations. However, due to the long orbital period it was still not enough data to prove that the orbit was not parabolic. He also recognized that the motion of Uranus was disturbed by another object and suspected that the cause was a planet unknown at that time, but whose position could not yet be calculated at that time. This succeeded more than 60 years later Urbain Le Verrier, whose calculations led to the discovery of the planet Neptune.[6]

Still, Lexell found data gathered by Christian Mayer in Pisces that was not in the Flamsteed catalogues. Lexell presumed that it was an earlier sighting of the same astronomical object and using this data he calculated the exact orbit, which proved to be elliptical, and proved that the new object was actually a planet. Anders Lexell also estimated the planet’s size more precisely than his contemporaries using Mars that was in the vicinity of the new planet at that time.

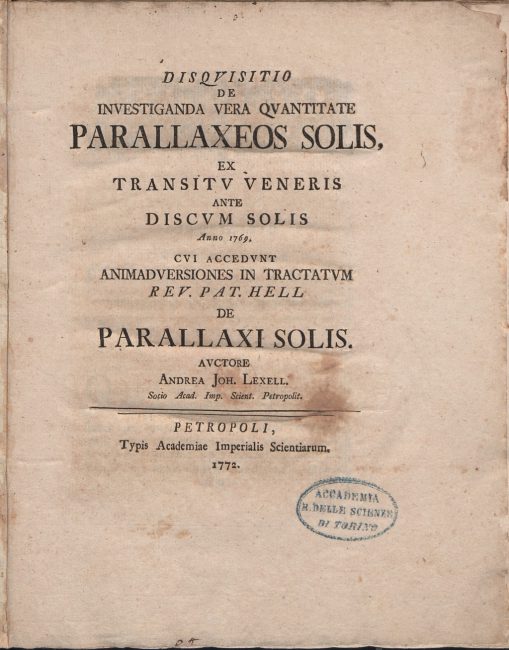

Disquisitio de investiganda vera quantitate (1767/1772)

The Friendship with Euler and Death

Anders Johan Lexell became very attached to Leonhard Euler, who lost his sight in his last years but continued working using his elder son Johann Euler to read for him. Lexell helped Leonhard Euler greatly, especially in applying mathematics to physics and astronomy. He helped Euler to write calculations and prepare papers. On 18 September 1783, after a lunch with his family, during a conversation with Lexell about the newly discovered Uranus and its orbit, Euler felt sick. He died a few hours later. After Euler’s passing, Academy Director, Princess Dashkova, appointed Lexell in 1783 to replace him. Lexell did not enjoy his position for long: he died on 30 November 1784, at age of only 43. In 1784, the year of his death, he was elected a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Scott Tremaine, Geometric Methods for Orbit Integration, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Anders Johan Lexell at MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive

- [2] Anders Johan Lexell at the SEDS Messier Database

- [3] Anders Johan Lexell at Wikidata

- [4] Read Euler, he is the Master of us all…, SciHi Blog

- [5] Charles Messier and the Nebulae, SciHi Blog

- [6] Urbain Le Verrier and the hypothetical Planet Vulcan, SciHi Blog

- [7] Scott Tremaine, Geometric Methods for Orbit Integration, Instituter for Advanced Study @ youtube

- [8] Stén, Johan C.-E. (2015): A Comet of the Enlightenment: Anders Johan Lexell’s Life and Discoveries. Basel: Birkhäuser

- [9] Bopp K. (1924). “Leonhard Eulers und Johann Heinrich Lamberts Briefwechsel”. Abh. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 2: 38–40.

- [10] Timeline of Finnish Astronomers, via DBpedia and Wikidata