Augustus, 1st Emperor of the Roman Empire

(63BC – 14AD), marble statue known as

Augustus of Prima Porta

On September 23, 63 BC, Gaius Octavius aka Imperator Caesar Divi F. Augustus, founder of the Roman Empire and first Emperor was born. The Roman Empire as a follow up of the former Roman Republic existed for almost four centuries, before it was divided up into Western and Eastern Roman Empire. While the western port deceased to exist in the 5th century AD, the eastern part continued to prosper for almost a millenium until the Ottoman invasion in the 15th century. Thus, at least for half of a millenium, Rome was the undisputed ruler of the western hemisphere and the man who laid the foundations of this empire was Gaius Octavius, who was a great-nephew and heir Gaius Julius Caesar.[5] It was Caesar, who shattered the cornerstones of the Roman Republic after the Civil War, when he became dictator for a lifetime, but it was Gaius Octavius who succeeded to establish an empire and a dynasty.

Adopted Posthumously By Julius Caesar

Born Gaius Octavius into an old and wealthy equestrian branch of the plebeian Octavii family in 63BC, Gaius was adopted posthumously by his maternal great-uncle Gaius Julius Caesar following Caesar’s assassination in 44BC. Having no living legitimate children, Caesar had adopted his great-nephew Octavius as his son and main heir. Octavius became Octavianus or Octavian. Styling himself “Caesar”, he gathered troops from Brundisium and along the road as he went to Rome to have his adoption made official. Although Marc Antony later charged that Octavian had earned his adoption by Caesar through sexual favors, the antique historian Suetonius describes Antony’s accusation as political slander. Marc Antony was his rival for power in Rome, and the two feuded for about a year, before forming the second triumvirate (with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus) forcing the Roman Senate to grant all three of them consular power for five years.

Joining Forces Against Caesar’s Murderers

Joining forces against Cassius and Brutus, the murderers of Caesar, Octavian and Antony prevailed at the battle of Philippi over the army of Ceasar’s assassins, and then divided the empire between them, Antony controlling the eastern provinces (including the wealthy Egypt) and Octavian controlling the west. For the next few years Antony and Octavian worked together to put down rebellions, but eventually Antony deserted his wife Octavia – Octavian’s sister, a marriage originally arranged to secure their alliance – and went to live with Cleopatra in Egypt.[6] This started an open conflict between the two leaders. Accusing Antony of setting up a power in Egypt to threaten Rome, the conflict was finally resolved at the naval battle of Actium in 31 BC when Octavian defeated the the combined forces of Antony and Cleopatra and and became the absolute power in Rome.

The End of the Civil War

With all strong opponents dead, the civil wars ended, soldiers settled with the wealth acquired from Egypt, Octavian – with universal support – assumed command and was consul every year from 31-23 BC. In 27 BC Octavian staged an offer to lay down his powers, but the Senate insisted he take most of the powers back and added to his adopted name of Caesar the title Augustus (meaning “divine” or “majestic”). In 30 or 23 B.C. Augustus became tribune for life, a title that he used to show his connection with the people, since the tribunate was a magistracy for the plebeians, common people, rather than the elite, the patricians. Being tribune also meant he had veto power. In addition, he was pontifex maximus, which meant he was in charge of religious observances. Moreover, Augustus held the right to convene the Senate, to speak first, and to propose legislation in the popular assembly. The Roman historian Tacitus writes about Augustus:

“[Augustus] seduced the army with bonuses, and his cheap food policy was successful bait for civilians. Indeed, he attracted everybody’s good will by the enjoyable gift of peace. Then he gradually pushed ahead and absorbed the functions of the senate, the officials, and even the law. Opposition did not exist. War or judicial murder had disposed of all men of spirit. Upper-class survivors found that slavish obedience was the way to succeed, both politically and financially. They had profited from the revolution, and so now they liked the security of the existing arrangement better than the dangerous uncertainties of the old régime. Besides, the new order was popular in the provinces. (1. 2)” — From The Annals of Tacitus

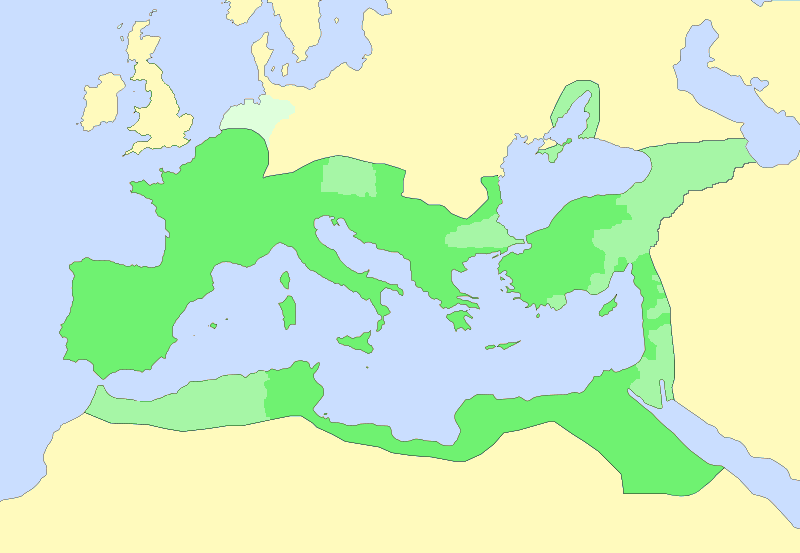

The Roman Empire under Emperor Augustus (dark green: Roman provinces, light green: dependent territories/client states, pale green: Germania province)

Forming A Dynasty

Over the next few decades the new powers of Augustus, the one leader of Rome had to be ironed out through two constitutional settlements and then the added title of Pater Patriae father of the country that was given him in 2 BC. Augustus dramatically enlarged the Empire, annexing Egypt, Dalmatia, Pannonia, Noricum, and Raetia, expanding possessions in Africa, and completing the conquest of Hispania, but suffered a major setback in Germania. Beyond the frontiers, he secured the Empire with a buffer region of client states and made peace with the Parthian Empire through diplomacy. He reformed the Roman system of taxation, developed networks of roads with an official courier system, established a standing army, established the Praetorian Guard, created official police and fire-fighting services for Rome, and rebuilt much of the city during his reign. Augustus died in 14 AD most likely from natural causes and was replaced by his stepson Tiberius, the son of Augustus’s second wife Livia. However, there were unconfirmed rumors that his wife Livia poisoned him.

Diana A. Kleiner, 9. From Brick to Marble: Augustus Assembles Rome, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Biography of Augustus at BBC History

- [2] Augustus at heritage history

- [3] The Life of Augustus in The Lives of the Twelve Caesars by C. Suetonius Tranquillus

- [4] The Life of Augustus by Nicolaus of Damascus

- [5] Veni, Vidi, Vici – According to Iulius Caesar, SciHi Blog

- [6] Cleopatra and the Myth of the Last Egyptian Pharaoh, SciHi Blog

- [7] Augustus at Wikidata

- [8] Diana A. Kleiner, 9. From Brick to Marble: Augustus Assembles Rome, Sep 11, 2009 Roman Architecture (HSAR 252), YaleCourses@ youtube

- [9] Eck, Werner; Takács, Sarolta A. (2003), The Age of Augustus, translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

- [10] Scullard, H. H. (1982) [1959]. From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68 (5th ed.). London; New York: Routledge.

- [11] Galinsky, Karl (2012). Augustus: Introduction to the Life of an Emperor. Cambridge University Press.

- [12] Timeline for Augustus via Wikidata