Abraham a Sancta Clara (1644-1709)

On December 1, 1709, Abraham a Sancta Clara, Austrian divine, court preacher and author passed away. Born as Johann Ulrich Megerle, he has been described “a very eccentric but popular Augustinian monk” and had earned great reputation for pulpit eloquence, the force and homeliness of his language, the grotesqueness of his humor, and the impartial severity with which he lashed the follies of all classes of society and of the court in particular. In his published writings he displayed many of the same qualities as in the pulpit. Perhaps the most favorable specimen of his style is his didactic novel entitled Judas der Erzschelm.

Early Years

Johann Ulrich Megerle was born on July 2, 1644, as the eighth of nine children to Matthias Megerle, a well-to-do serf who kept a tavern in Kreenheinstetten, a small town in Suabia, today Southern Germany. At the age of six he attended the local village school in his native place and from 1656-59, he continued his education the Jesuit Untergymnasium in Ingolstadt. At his father’s death, the boy was adopted by his uncle, Abraham von Megerlin, canon of Altötting, who removed him to the Benedictine school in Salzburg. At the age of 18, Johann joined the Discalced Augustinians at Vienna, choosing the name Abraham a Sancta Clara and completed his theological studies at Mariabrunn, not far from Vienna until his ordination in 1666.

Imperial Court Preacher

In 1677, he was appointed imperial court preacher by Leopold I, and while holding this office experienced the terrors of the year of the plague, 1679. For 1680 he is recorded as being prior of the convent at Vienna, and in 1682 he went to Graz as chaplain to the monastic church of his order, first as Sunday preacher, and later as prior. He continued as a court preacher again in Vienna and became prior provincialis and later definitor of his province. Abraham a Sancta Clara died at Vienna on 1 December 1709.

The Harlequin of the Pulpit

Abraham had at his command an amazingly large amount of information which, with an abundant wit in keeping with the taste of his time, made him an effective preacher. His peculiar talent lay in his faculty for presenting religious truths, even the most bitter, with such graphic charm that every listener, both high and low, found pleasure in his discourse, even though certain of his contemporaries expressed themselves with great virulence against “the buffoon, the newsmonger, and the harlequin of the pulpit.” Even in his character of author, he stands as it were in the pulpit, and speaks to his readers by means of his pen. His works are numerous.[1]

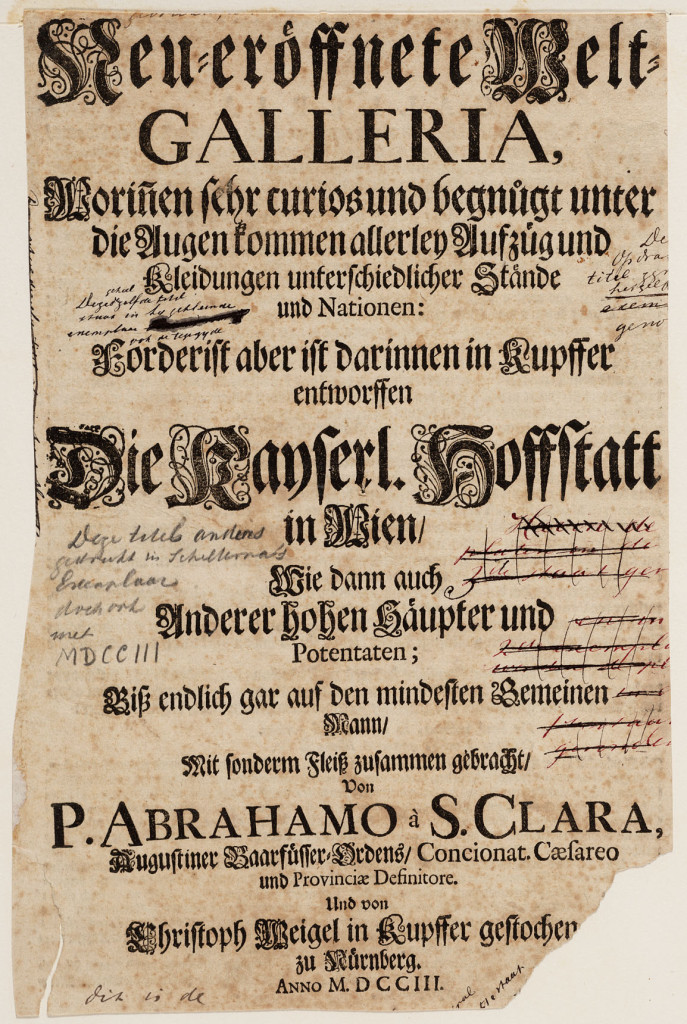

Abraham a Sancta Clara, Neueröffnete Welt-Galleria (1703)

Against the Ottoman “Arch-Enemy”

As a reaction to the plague epidemics that erupted in Vienna in 1679, Abraham a Sancta Clara composed Mercks Wienn (Vienna, Mark it Well, 1680), that appeared in 1680 and immediately became a bestseller. This book, which contained powerful illustrative language and combined the genres of a plague treatise and fraternity book with the Totentanz tradition and upbuilding literature, ensured him a lasting recognition and popularity.[2] The Turkish invasion, which at last led to the siege of Vienna in July 1683, was the impetus that prompted Abraham a Sancta Clara to write his call for resistance against the Ottoman “arch-enemy” entitled Auff auff ihr Christen (Arise, arise you Christians, 1683).[2] Perhaps the most favorable specimen of his style is his didactic novel entitled Judas der Erzschelm (Judas, the Arch-Rascal, 1686-1695). This treats of the apocryphal life of the traitor Judas, and is varied with many moral reflections.

Moral Pedagogy

Abraham a Sancta Clara published works in a wide variety of genres, many of which saw a number of reprinted editions, including a German edition of Grammatica Religiosa, published in 1699 in Cologne. In 1707 appeared the moral pedagogical work Huy! und Pfuy! Der Welt, which coupled the texts of Abraham a Sancta Clara with the exquisite engravings of Jan Luyken (1649–1712). After his death Abraham a Sancta Clara remained a popular author, which prompted the publication of his Nachlass and the production of various compilations and apocrypha.[2] Some of his late works showed the influence of Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools),[4] which was even more apparent in Centifolium stultorum in Quarto (A Hundred excellent fools in Quarto, 1709), and Wunderwürdiger Traum von einem grossen Narrenest (Wonderful Dream of a Great Nest of Fools, 1710).

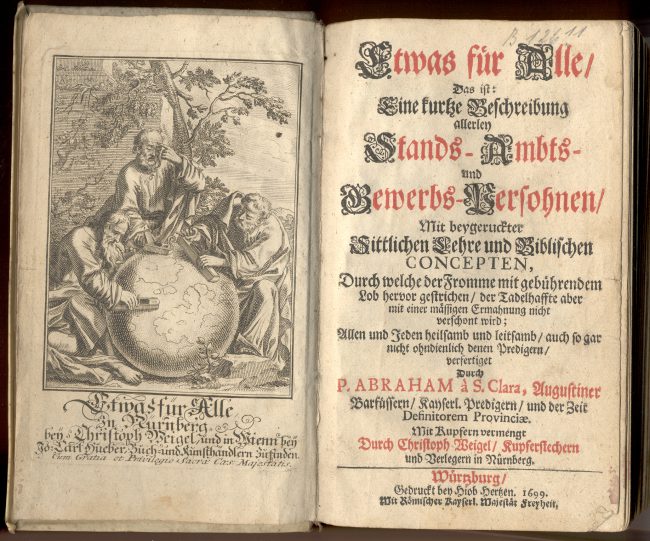

Abraham a S. Clara: Etwas für alle (1699)

Friedrich Schiller,[5] a Swabian compatriot of Abraham, has passed this interesting judgment on the literary monk in a letter to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe:[6] “This Father Abraham is a man of wonderful originality, whom we must respect, and it would be an interesting, though not at all an easy, task to approach or surpass him in mad wit and cleverness.” Moreover, Schiller was greatly influenced by Abraham a Sancta Clara.[1]

The various ministries and the continued preaching and writing had undermined his health, in addition to many years of suffering from gout. He died on 1 December 1709 at the age of 65 and was buried in the crypt of the Augustinian Church in Vienna. As a priest Abraham mainly pursued pastoral intentions with his work. His aim, which is often stated in the titles and prefaces of his works, is to bring people to their salvation. Since he thinks in terms of salvation history, he assigns all human actions to the contrasting concepts of salvation and sin. In his moral doctrine he praises the Christian virtues embodied in the saints, denounces the vices and also preaches against Judaism. The success of his works and his sermons was also based on the fact that Abraham a Sancta Clara took into account the reality of the lives of his listeners and readers, as for example in his teaching of the state Something for All. Abraham’s lowly background made him credible for his listeners; he himself called his sermon method “looking the people in the eye“.

References and further Reading:

- [1] Abraham a Santa Clara at The Catholic Encyclopedia

- [2] Peter Šajda: Abraham a Sancta Clara: An Aphoristic Encyclopedia of Christian Wisdom

- [3] Abraham a Sancta Clara’s original Writings, at wikisource

- [4] Sebastian Brant and the Ship of Fools, SciHi Blog blog, March 10, 2013.

- [5] ‘Art is the Daughter of Freedom’ – Friedrich Schiller, SciHi Blog

- [6] The Life and Works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, SciHi Blog

- [7] Abraham a Santa Clara at Wikidata

- [8] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Abraham a Sancta Clara“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 72.

- [9] Stadtverwaltung Graz: Abraham a Sancta Clara

- [10] Wilhelm Scherer: Megerlin, Johann Ulrich. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 21, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1885, S. 178–181.