Jacques Alexandre César Charles (1746 – 1823)

On November 12, 1746, French inventor, scientist, mathematician, and balloonist Jacques Alexandre César Charles was born.Charles and the Robert brothers launched the world‘s first (unmanned) hydrogen-filled balloon in August 1783. In December 1783, Charles and his co-pilot Nicolas-Louis Robert ascended to a height of about 500 metres in a manned balloon. Their pioneering use of hydrogen for lift led to this type of balloon being named a Charlière (as opposed to a Montgolfière which used hot air).[3]

Jacques Charles – From Finance to Science

Jacques Charles was born in Beaugency-sur-Loire, in the Loiret department, Centre-Val de Loire, north-central France, in 1746. Even though his first occupation was as a clerk at the Ministry of Finance in Paris, his interests eventually turned to science. It is believed that through the work of Robert Boyle‘s and Boyle‘s Law, Charles conceived the idea that hydrogen would be a suitable lifting agent for balloons. Further, contemporary scientists who influenced Charles on the matter were Henry Cavendish, Joseph Black and Tiberius Cavallo.

The Airtight Shell

Charles proceeded to design and craft together with the Robert brothers, Anne-Jean and Nicolas-Louis, to build it in their workshop at the Place des Victoires in Paris. The brothers managed to invent the methodology for the leightweight, airtight gas bag by dissolving rubber in a solution of turpentine and varnished the sheets of silk that were stitched together to make the main shell. They used alternate strips of red and white silk, but the discolouration of the varnishing/rubberising process left a red and yellow result.

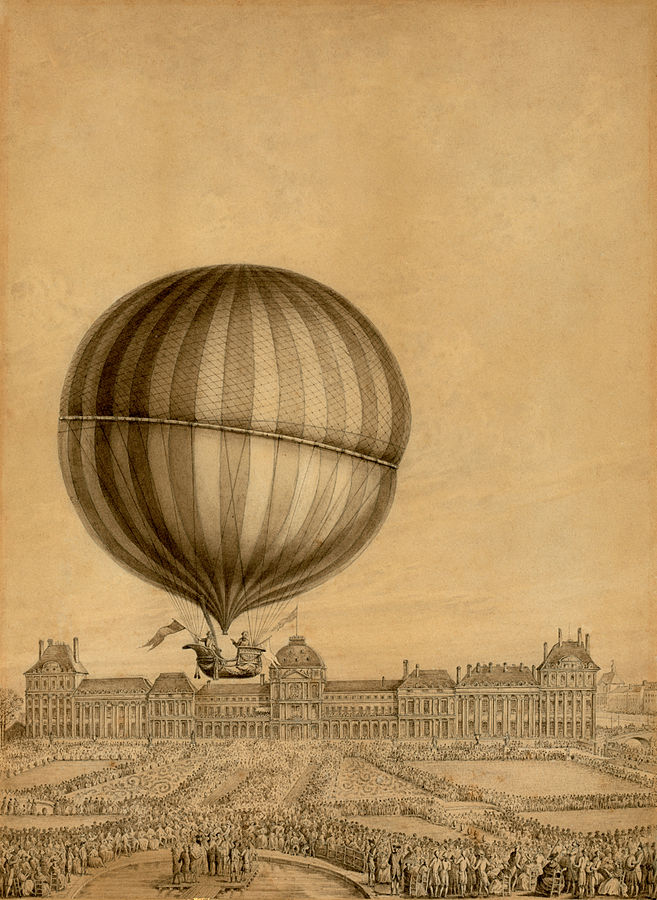

Departure of Jacques Charles and Marie-Noel Robert’s ‘aerostatic globe’ balloon from the Jardin des Tuileries, Paris

First Flight

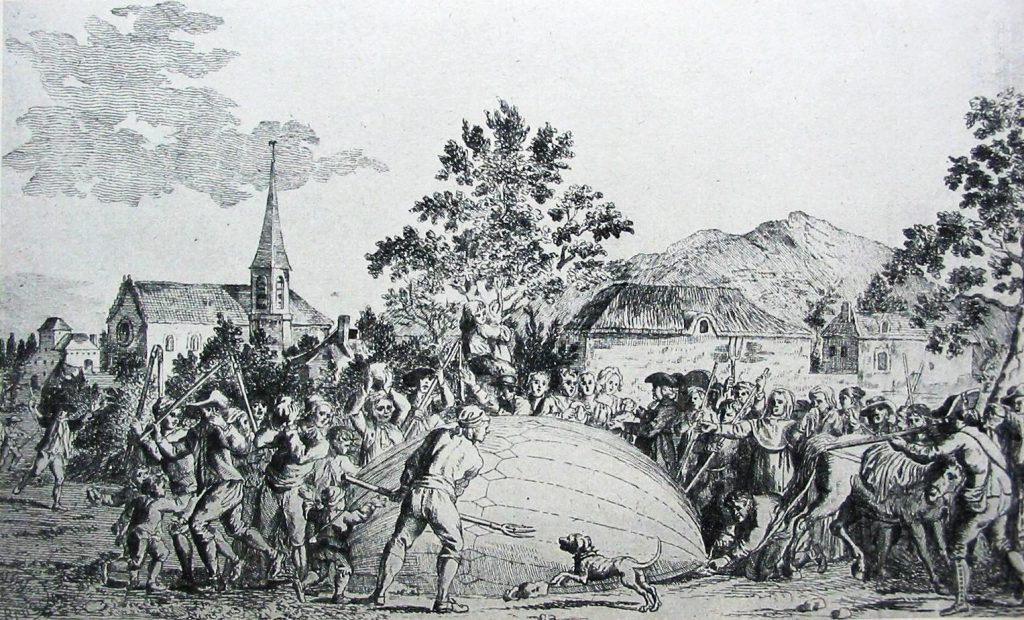

The world’s first (known) hydrogen filled balloon was launched by Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers on August 27, 1783, from the Champ de Mars, (today’s site of the Eiffel Tower) where Benjamin Franklin [4] was among the crowd of onlookers. The balloon measured 35 cubic metre sphere of rubberised silk, and was capable of lifting circa 9 kg. It was filled with hydrogen that had been made by pouring nearly a quarter of a tonne of sulphuric acid onto a half a tonne of scrap iron. The hydrogen gas was fed into the balloon via lead pipes; but as it was not passed through cold water, great difficulty was experienced in filling the balloon completely. Daily progress bulletins were issued on the inflation; and the crowd was so great that on the 26th the balloon was moved secretly by night to the Champ de Mars, a distance of 4 kilometres. The balloon flew northwards for 45 minutes, pursued by chasers on horseback, and landed 21 kilometers away in the village of Gonesse where the reportedly terrified local peasants destroyed it with pitchforks or knives. When someone asked American ambassador Benjamin Franklin what purpose this new invention had, he answered with the counter question: “What purpose does a newborn child have?“

The trial balloon that bursts near Gonesse causes an uprising among the inhabitants. Led by the clergy, they pounce on the “devil’s device” and finish it off.

Manned Flight

Charles made his first manned flight together with Marie-Noël Robert on December 1, 1783, taking almost three days to produce the necessary hydrogen gas from iron filings and sulfuric acid. They stayed in the air for two hours and landed in the village of Nesles-la-Vallée, 36 kilometers away. After that, Charles ascended once more on his own. This made him the first person to ride alone in a balloon. This event took place ten days after the world’s first manned balloon flight by Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier using a Montgolfier brothers hot air balloon.. That aside, Charles could chalk up the flight as a success because he had also proved that it was not smoke that made the balloon rise. During his balloon flight, he had a barometer and a thermometer on board. With the help of the former, he was able to determine that his greatest altitude reached was 3467 m.

Further Achievements

The next project of Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers was to build an elongated, steerable craft that followed Jean Baptiste Meusnier‘s proposals (1783–85) for a dirigible balloon. The design incorporated Meusnier’s internal ballonnet (air cells), a rudder and a method of propulsion. Although Charles never flew this design, on September 19, 1784 the Robert brothers and M. Collin-Hullin flew for 6 hours 40 minutes, covering 186 km from Paris to Beuvry near Béthune. This was the first flight over 100 km. Charles developed several useful inventions, including a valve to let hydrogen out of the balloon and other devices, such as the hydrometer and reflecting goniometer, and improved the Gravesand heliostat and Fahrenheit’s aerometer. In addition he confirmed Benjamin Franklin’s electrical experiments.

Later Years

During the French Revolution, Charles hid a refractory priest and thus risked being arrested although he was not a very fierce revolutionary, but only one of those enlightened bourgeois of the end of the 18th century who reconciled faith with the new ideas without rejecting the monarchical principle. In 1804, at the age of 57, Jacques Charles married a Creole woman much younger than himself, Julie Bouchaud des Hérettes (1784-1817), who became the muse of Alphonse de Lamartine. Jacques Charles died on April 7, 1823 in Paris and was buried in the Père-Lachaise cemetery.

Jakko Hoekstra, Ballooning – Introduction to Aeronautical Engineering [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Jacques Charles Biography

- [2] J.B. Gough, 1979. “Charles The Obscure“

- [3] More than just hot air – the Montgolfier-Balloons, SciHi Blog

- [4] Benjamin Franklin and the Invention of the Lightning Rod, SciHi blog

- [5] Fiddlers Green, History of Ballooning, Jacques Charles

- [6] . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- [7] Claude-Joseph Blondel, Un enfant illustre de Beaugency : le physicien et aéronaute Jacques Charles (1746-1823) coll. Les Publications de l’Académie d’Orléans, agriculture, sciences, belles-lettres et arts, Orléans, Académie d’Orléans, 2003.

- [8] Jacques Alexandre César Charles At Wikidata

- [9] Jakko Hoekstra, Ballooning – Introduction to Aeronautical Engineering, AE1110x – W01_1c – Ballooning I, ©️ TU Delft, released under a CC BY NC SA license, Delft-X Aero @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of French aviation pioneers, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #18 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #13 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Bean thinking » Up in the air with a Pure Over Brewer