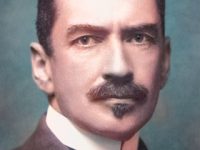

Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937)

On December 12, 1901, Italian born engineer Guglielmo Marconi succeeded with the very first radio transmission across the Atlantic, by receiving the first transatlantic radio signal at Signal Hill in St John’s, Newfoundland transmitted by the Marconi company’s new high-power station at Poldhu ,Cornwall. The distance between sender and receiver was about 3,500 kilometres (2,200 mi) and with this groundbreaking long distance record the era of wireless telecommunication started.

“Have I done the world good, or have I added a menace?”

– Guglielmo Marconi, 1934: as cited in [8]

Guglielmo Marconi – Youth and Education

Guglielmo Marconi was born in Bologna on 25 April 1874, the second son of Giuseppe Marconi, an Italian landowner, and his Irish/Scots wife, Annie Jameson. Together with his older brother Alfonso he spent his early childhood with his mother from 1879 to 1881 in the English town of Bedford at a private school, then returned with his family to Italy and went to Florence until the age of 14, then to Livorno for two years, to school, where he also received private lessons in natural sciences from Vincenzo Rosa. In the summer of 1892 he attended a number of lectures by Augusto Righi and Bernardo Dessau at the University of Bologna, but never achieved university entrance and admission to regular university or military academy studies. The particular subject Marconi was interested in came from German physicist Heinrich Hertz, who, beginning in 1888, demonstrated that one could produce and detect electromagnetic radiation— now generally known as radio waves.[3]

The Idea of Wireless Communication

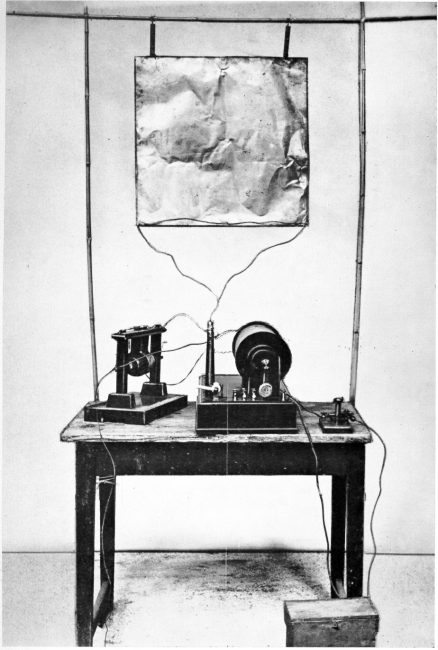

Although he never had any formal university education, Marconi began to conduct experiments, building much of his own equipment in the attic of his home at the Villa Griffone in Pontecchio, Italy, with the help of his butler Mignani. His goal was to use radio waves to create a practical system of “wireless telegraphy”. This was not a new idea. Numerous scientists and inventors had been exploring wireless telegraph technologies for over 50 years, but none had proven technically nor commercially successful. As a transmitter, he used pop radio transmitters, modified the setups in various details and tried out various improvements in experiments.

The Detector

In the summer of 1895, he also carried out some of his experiments over a distance of 1.5 km in Salvan in the Swiss Alps. In 1896, Marconi built a “device for detecting and recording electrical vibrations”. The detection of high-frequency oscillations was then based on the so-called coherer, which contained metal filings in a thin glass tube. The received high-frequency oscillation changes the electrical resistance of the arrangement, whereby various parameters such as the grain size and the alloy of the metal chips used have a significant influence on the function. Different types of coherors had already been used by Édouard Branly in 1890 and independently by Alexander Stepanowitsch Popow in 1893. Popow, however, did not use the coherer for receiving messages but for detecting lightning discharges.

Patent Quarrels

In 1895 Marconi succeeded in sending wireless signals over a distance of one and a half miles and already one year later he took his equipment to England where he was introduced to Sir William Preece, Engineer-in-Chief of the Post Office, and later that year was granted the world’s first patent for a system of wireless telegraphy. Impressed by Marconi’s system, Preece subsequently became a supporter of Marconi. In December of the same year, Preece gave a demonstration of Marconi’s transmission system, where he claimed that Marconi was the inventor of wireless messaging. This led to opposition, especially in academic circles and at Oliver Lodge, as major contributions to Marconi’s radio system also came from Lodge. However, Lodge had failed to recognize the corresponding practical significance in earlier works and discoveries and to protect the inventions under patent law.[4]

Marconi’s first transmitter incorporating a monopole antenna.[10]

Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company

Marconi demonstrated his system successfully in London, on Salisbury Plain and across the Bristol Channel, and in July 1897 formed The Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company Limited that was re-named in Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company Limited in 1900. In the same year he gave a demonstration to the Italian Government at Spezia where wireless signals were sent over a distance of twelve miles. In 1899 he established wireless communication between France and England across the English Channel and erected permanent wireless stations at The Needles, Isle of Wight, at Bournemouth and later at the Haven Hotel, Poole, Dorset.

Crossing the Atlantic

By transmitting signals from ship to shore over a 66 nautical mile span, far more than enough to ensure that the waves were somehow bending around or traveling through the ocean to reach the shoreline. Marconi was convinced that the wireless could span the ocean and he set out to prove it. He had a powerful transmitting station built in Poldu on the English coast and established another station at St Johns, Newfoundland. There he was working in secret, pretending to contact passing ships on their transatlantic voyages, he launched a kite with a receiving wire more than 100 meters into the air. On December 12, 1901, he was able to receive the letter “S” several times and had an assistant verify the reception, before he announced to the world what he had done. He had received the very first wireless radio message from over 3,500 kilometers across the Atlantic.

Wireless Communication for Ships

Still, many doubted due to the bias of his only witness and the simplicity of the message. So Marconi next outfitted a ship with a sophisticated wireless equipment, a telegraph recorder that would mark the signals on paper tape, and a public listening room so that passengers and crew would be witness to receptions. With this equipment he succeeded in receiving signals over 3,000 kilometers from England. Another of his findings was however that the signals traveled the distance best at night, a phenomenon he was not able to explain. Finally, in 1907, Marconi perfected the system of transatlantic wireless and began commercial service between Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, Canada and Clifden, Ireland. For his work on wireless Marconi was honored with the Nobel Prize for physics in 1909.

Later Years

Due to his contribution to wireless telegraphy, Marconi was offered a free passage for the maiden voyage of the RMS Titanic in April 1912.[5] However, he had correspondence to attend to and therefore took the RMS Lusitania three days earlier as there was a stenographer on board. When Marconi died on 20 July 1937, all radio traffic worldwide was suspended for two minutes in his memory.

David Tse, Fundamentals of Wireless Communications I, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Biography of Guglielmo Marconi from Dr. Stephen D. Perry, Illinois State University

- [2] Biography of Guglielmo Marconi at nobelprize.org

- [3] Heinrich Hertz and the Successful Transmission of Electromagnetic Waves, SciHi Blog

- [4] Oliver Lodge and the Development of Radio Technology, SciHi Blog

- [5] Titanic – the Unsinkable Ship and the Iceberg, SciHi Blog

- [6] . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

- [7] Newspaper clippings about Guglielmo Marconi in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [8] Raboy, Marc (2016) Marconi: The Man Who Networked the World, p. 631

- [9] David Tse, Fundamentals of Wireless Communications I, Fundamentals of Wireless Communications I, UC Berkeley, The Qualcomm Institute @ youtube

- [10] Guglielmo Marconi, “Looking back over thirty years of radio”, Radio Broadcast magazine, Doubleday, Page, and Co., New York, Vol. 10, No. 1, November 1926, p. 31

- [11] Guglielmo Marconi at Wikidata

- [12] Timeline for Guglielmo Marconi, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #22 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #18 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #37 | Whewell's Ghost