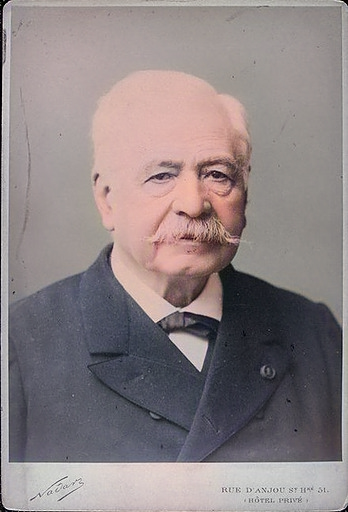

Ferdinand de Lesseps (1805 – 1894), photo by Félix Nadar circa 1872 – 1876 in Paris.

On November 19, 1805, French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal Ferdinand Marie, Vicomte de Lesseps was born. The Suez Canal that was constructed under de Lessep’s supervision in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times between the West and the East.

“Since 1849 I have studied incessantly, under all its aspects, a question which was already in my mind [since 1832. I confess that my scheme is still a mere dream, and I do not shut my eyes to the fact that so long as I alone believe it to be possible, it is virtually impossible. … The scheme in question is the cutting of a canal through the Isthmus of Suez. This has been thought of from the earliest historical times, and for that very reason is looked upon as impracticable. Geographical dictionaries inform us indeed that the project would have been executed long ago but for insurmountable obstacles.”

– Ferdinand de Lesseps on his inspiration for the Suez Canal, Letter to M.S.A. Ruyssenaers, Consul-General for Holland in Egypt, from Paris (8 Jul 1852), seeking support. [9]

Derdinand Marie de Lesseps – Family Background

Ferdinand de Lesseps was born at Versailles, Yvelines, in 1805 into a family of French career-diplomats. His first years were spent in Italy, where his father was occupied with his consular duties. His mother Catherine was of Spanish descent. Ferdinand visited his cousin, the Comtesse de Montijo, where he met her daughter Eugénie, who became Empress of France in 1853 as the wife of Napoleon III. His uncle, Jean Baptiste Barthélemy de Lesseps, was also a diplomat. De Lesseps was educated at the College of Henry IV in Paris. From the age of 18 years to 20 he was employed in the commissary department of the army.He entered the diplomatic career in 1825 and from 1825 to 1827 he acted as assistant vice-consul at Lisbon, where his uncle, Barthélemy de Lesseps, was the French chargé d’affaires. This uncle was an old companion of French explorer Jean-François de La Pérouse and the only survivor of the expedition in which La Pérouse perished.[4]

Tunisia and Egypt

Following the profession of his father, Ferdinand de Lesseps during his early career was posted to Tunisia and Egypt. In 1832 de Lesseps was appointed vice-consul at Alexandria. Fortunately for de Lesseps, Mehemet Ali, the viceroy of Egypt, owed his position in part to the recommendations made on his behalf to the French government by Mathieu de Lesseps, who was consul-general in Egypt when Ali was a colonel. Because of this, de Lesseps received a warm welcome from the viceroy and became good friends with his son, Said Pasha. De Lesseps became fascinated with the cultures of the Mediterranean and Middle East and the growth of western European trade. At the end of 1837 Lesseps returned to France and married Agathe Delamalle, with whom he had five children; she died 1853 together with a child of scarlet fever. From 1838 he successively administered the consulates in Rotterdam, Málaga and Barcelona, and in April 1848 he was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary of the French Republic in Madrid. At the beginning of 1849, he was sent on an extraordinary mission to the Roman Republic, created in the revolutions of 1848/49 and the Risorgimento. There he sought a friendly agreement between the provisional government there and France. The French government, determined to forcibly subjugate Rome to papal rule, dismissed him and he retired from the diplomatic service.

The Idea of a Canal

The idea of a Canal connecting the Mediterranean Sea with the Red Sea is old. Basically, it would allow large ships wishing to sail to the east to go directly from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, thereby cutting out the long sea journey around Africa. The Bubastis ChanCanalel was already established in ancient Egypt, but it did not connect the Mediterranean directly with the Red Sea, but led from the Nile delta via the Wadi Tumilat and Lake Timsah to the Red Sea. What seems certain, however, is that Necho II. (610 to 595 BC) built a canal from Bubastis in the eastern Nile delta (today’s Zagazig) through the Wadi Tumilat, but could not complete it. The Persian king Darius I (521 to 486 BC) established the connection to the Red Sea and documented this with four steles erected on the banks of his canal. Under the Ptolemies the canal was renewed with partly different routing, but was again silted up or silted up at Cleopatra’s time. Emperor Trajan (98 to 117 AD) built a connecting canal from Cairo to the Bubastis Canal around 100 AD and renewed it. This canal, also maintained by its successors, seems to have been used for a long time in trade with the south and east. After the Arabs conquered Egypt, Amr ibn al-As, a general of Mohammed who ruled Egypt from 641 to 644 A.D., had the canal restored to supply the Arab sites with grain and as a transport route for the pilgrims. Al-Mansur, the second Abbasid caliph, is said to have ordered the closure of the canal in 770 as a measure against his enemies in Medina. The canal, which was over 200 km long from Cairo to Sues, was not restored after that, except for the fact that a section was used in the 19th century for the construction of the freshwater canal (see above).

A Canal of the Two Seas

A canal through the isthmus of Sues with its flat elevations, marshes and salt depressions was, so to speak, marked out by nature. This is why the idea of canal construction has remained alive through the centuries. Napoleon Bonaparte took up the idea to disrupt British trade with India. The measurements of the isthmus carried out by Jacques-Marie Le Père during his Egyptian expedition in 1799 under difficult circumstances, however, came to the wrong conclusion that the Red Sea was about ten metres higher than the Mediterranean Sea. After his retirement from the diplomatic service, de Lesseps retreated to his country estate Manoir de la Chesnaye, where the reports of Jacques-Marie Le Père and Linant de Bellefonds came to his attention again in his old files. He was so taken by the idea of the Canal des deux mers (Canal of the Two Seas), which was generally discussed at that time, that in 1852 he even wrote a memorandum on it, had it translated into Arabic and sent to the then Viceroy Abbas I, but without further consequences. In 1854 Lesseps learned that Abbas I had died and that Muhammad Said had been appointed viceroy, and congratulated Said Pasha immediately, who responded with an invitation to Egypt. Lesseps arrived in Alexandria on 7 November 1854. On one of his trips to the desert, on 15 November 1854, he presented him with a memorandum on the merits of a canal through the isthmus. Already on November 30, 1854, Lesseps received the concession from Said Pasha to build and operate the canal for 99 years with the Compagnie universelle du canal maritime de Suez (Suez Canal Company), which was to be founded.

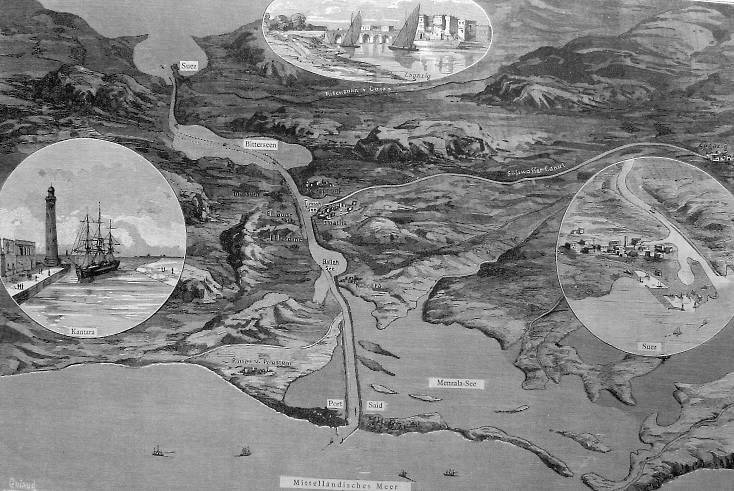

Diagram of the Suez Canal from 1882

The Modern Suez Canal

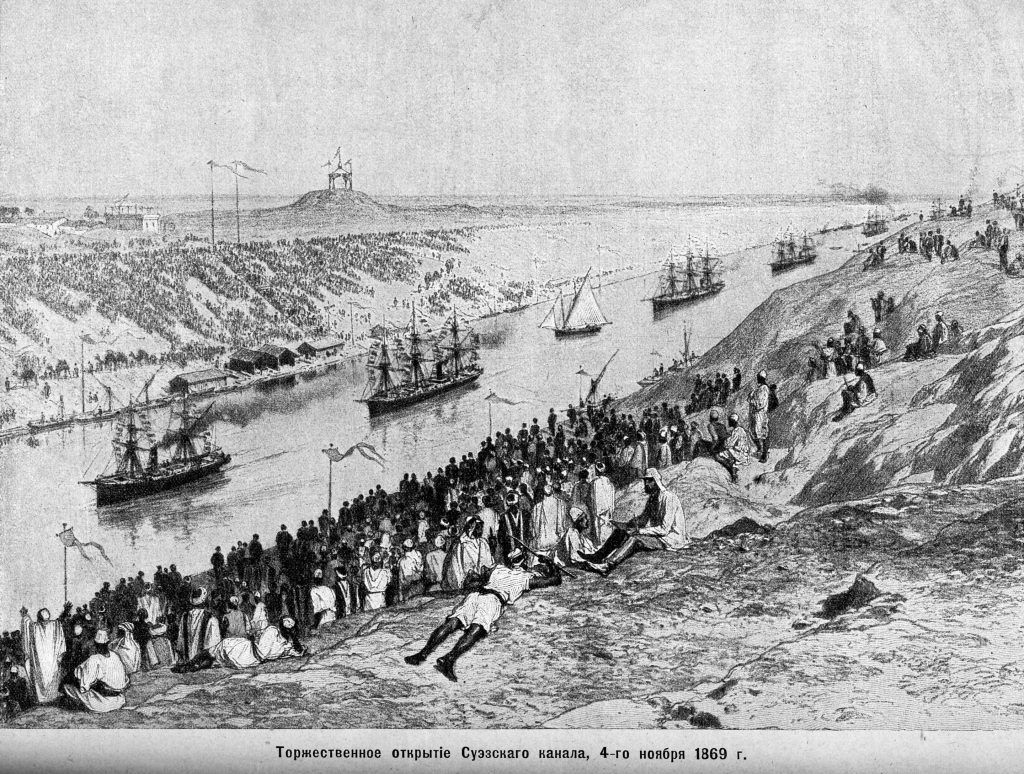

A first scheme, directed by Lesseps, was immediately drawn up by the surveyors Linant Bey and Mougel Bey providing for direct communication between the Mediterranean and Red Sea, and, after being slightly modified, it was adopted by an international commission of engineers in 1856.[2] The Compagnie universelle du canal maritime de Suez was organized at the end of 1858. On 25 April 1859 the first blow of the pickaxe was given by de Lesseps at Port Said. During the following ten years, de Lesseps had to overcome the continuing opposition of the British government preventing the Sultan from approving the construction of the canal, and at one stage he even had to seek the support of his cousin, Empress Eugenie, to persuade the Emperor Napoleon III to act as arbitrator in the disputes. Finally, on 17 November 1869, the canal was officially opened by the Khedive, Ismail Pasha. Despite several futile trials, de Lesseps had failed to get also support for his project by the British government. British attitudes finally changed when the canal was seen to be a success and de Lesseps was treated as a great celebrity on his subsequent visit to Britain. In 1875, the Egyptian government sold its shares in the canal and the British prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, bought effective control of the Canal Company.

Opening of the Suez Canal, 1869

More Canals ahead

In his 74th year, de Lesseps began to plan a new canal in Panama.[5] In 1879, an international congress was held in Paris, which chose the route for the Panama Canal and appointed de Lesseps as leader of the undertaking. However, the decision to dig a Panama Canal at sea level to avoid the use of locks, and the inability of contemporary medical science to deal with epidemics of malaria and yellow fever, doomed the project. The Panama Canal Company declared itself bankrupt in December 1888 and entered liquidation in February 1889. The failure of the project is sometimes referred to as the Panama Canal Scandal, after rumors circulated that French politicians and journalists had received bribes. A French court found de Lesseps and his son Charles guilty of mismanagement. Both were heavily fined and sentenced to imprisonment. In the event, de Lesseps did not go to jail, but his son paid for his elderly father’s misjudgements with a year in prison. De Lesseps died on 7 December 1894.

Charles Keith, French Imperialism, Guest Lecture, Yale [9]

References and further Reading:

- [1] Ferdinand de Lesseps at BBC History

- [2] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Lesseps, Ferdinand de“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 494–496.

- [3] Ferdinand de Lesseps at Association Lesseps

- [4] Jean-François de La Pérouse and his Voyage around the World, SciHi Blog

- [5] The Opening of the Panama Canal, SciHi Blog

- [6] Encyclopedia of the Orient: Suez Canal

- [7] Ferdinand de Lesseps at WIkidata

- [8] Ferdinand de Lesseps, The Suez Canal: Letters and Documents Descriptive of Its Rise and Progress in 1854-1856 (1876), 2

- [9] Charles Keith, French Imperialism, Guest Lecture, France Since 1871 (HIST 276), Yale Courses @ youtube

- [10] Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the Desert: The Creation of the Suez Canal. New York: Knopf.

- [11] Ferdinand de Lesseps (1887). Recollections of forty years. Volume 1. Volume 2.

- [12] Map with Ship Canals, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #14 | Whewell's Ghost