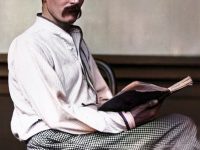

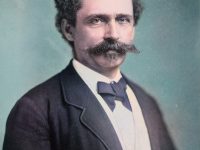

![Sir Henry "Harry" Hamilton Johnston, GCMG, KCB, D.Sc. Cambs.,[1] (12 June 1858 – 31 July 1927), was a British explorer, botanist, linguist and colonial administrator, one of the key players in the "Scramble for Africa" that occurred at the end of the 19th century.](http://scihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Portrait_of_Harry_Johnston-740x1024.jpg)

Sir Harry Johnston (1858-1927)

On June 12, 1858, British explorer, botanist, linguist and colonial administrator Sir Harry Johnston was born. His interest in zoological specimens gave him a lucrative part-time income, illustrating books for the new sciences of biology, geography and anthropology. Moreover, he is probably best known for being one of the key players in the “Scramble for Africa” that occurred at the end of the 19th century.

“In our land the educated poor, who at the most can only cycle or take short railway journeys into the country from an adjoining town, are fast losing their rightful heritage — the beauty of the country-side, which is rapidly disappearing with very little benefit to anyone. Apparently nobody but a few timid adherents of the Archeological Society cares a straw.”

– Harry Johnston, as quoted in [8]

Harry Johnston – Early Years

Harry Johnston was born in London, the eldest of 12 children of Esther and John Johnston, a wealthy and well-traveled insurance company director. Henry Johnston discovered his aptitude for drawing, painting, and languages at an early age. After attending Stockwell grammar school, he pursued the study of languages at King’s College, University of London, but in 1875 he became a pupil of painting at the Royal Academy. In connection with his study he travelled to Europe and North Africa, visiting the little-known interior of Tunisia from 1879 to 1882.

The River Kongo

In 1882 Henry Johnston visited southern Angola with the Earl of Mayo, an enthusiastic amateur zoologist and adventurer, and in the following year he met famous explorer Henry Morton Stanley in the Congo, becoming one of the first Europeans after Stanley to see the river above the Stanley Pool. With the publication of his book The River Congo (1884) and a number of articles in British periodicals, Johnston achieved a degree of recognition as an Africanist and explorer. In 1883, he was elected fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. His developing reputation led the Royal Geographical Society and the British Association to appoint him leader of an 1884 scientific expedition to Mount Kilimanjaro. On this expedition he concluded treaties with local chiefs in competition with German efforts to do likewise. The results of this journey were significant botanically and linguistically. The account of his travel was published in 1886 as The Kilimanjaro Expedition with his own magnificent illustrations.

Vice Consul of Cameroon

In October 1886 the British government appointed him vice-consul in Cameroon and the Niger River delta area, where a protectorate had been declared in 1885, and he became acting consul in 1887. On leave in England in 1888, he met with Lord Salisbury and apparently helped formulate the Cape to Cairo plan to acquire a continuous band of territory down Africa, which he then leaked to the Times in an anonymous article “by an African Explorer“. Between 1888 and 1891 he exercised much influence on British African policy and obtained the treaties on which the United Kingdom based its claims to Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia.[2] From 1889 to 1896 Johnston, as Her Majesty’s commissioner and consul general for Mozambique and the Nyasa districts, created the nucleus of modern Malawi and personally articulated and directed the development of British energies in the trans-Zambezian regions of Central Africa.[1]

Strategic Importance

Johnston realised the strategic importance of Lake Tanganyika to the British, especially since the territory between the lake and the coast had become German East Africa forming a break of nearly 900 km in the chain of British colonies in the Cape to Cairo dream. However the north end of Lake Tanganyika was only 230 km from British-controlled Uganda, and so a British presence at the south end of the lake was a priority.

The Uganda Agreement

From 1899 to 1901 Johnston created the basis of modern Uganda. Although the protectorate had been in existence for 7 years, he, as special commissioner and commander in chief, arranged the settlement of internal difficulties known as the Uganda Agreement. Johnston gave the Ganda, the dominant people in the southern sector of the country, considerable political and territorial advantages over the other hierarchically organized peoples of the protectorate. While in 1870, only 10 percent of Africa was under European control, by 1914 it was 90 percent of the continent, with only Abyssinia (Ethiopia) and Liberia still being independent.

Later Years

Johnston was knighted in 1896. Afflicted by tropical fevers, he transferred to Tunis as consul-general and then was special commissioner in Uganda (1899–1901). In 1903 and in 1906 he stood for parliament for the Liberal Party, but was unsuccessful on both occasions. After his retirement, he moved together with his family to West Sussex in 1906, where he largely concentrated on his literary endeavours and continued his naturalist studies. In 1925, Harry Johnston suffered two strokes from which he became partially paralysed and never recovered, dying two years later in 1927. Harry Johnston was the very model of the multi-talented African explorer; he was fluent in Spanish, French, Arabic, Portuguese and Italian; he knew 30 African languages; he exhibited paintings, collected flora and fauna, climbed mountains, wrote books, signed treaties, and ruled colonial governments. During his travels he discovered and described more than 100 species of birds, invertebrates, reptiles and mammals. The most significant of all the discoveries, was the okapi, a kind of artiodactyls (closely related to the giraffe), outwardly resembling a horse, which was the zoological sensation of the 20th century. Like his fellow imperialists he believed in British and European superiority over Africans. Nevertheless, his views differ from his contemporaries in the point that colonial rulers should always try to understand the culture of the subjugated peoples.

John Young, Flagler College HIS 363 Modern Africa: The Scramble for Africa, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “Sir Henry Hamilton Johnston.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004.

- [2] Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston, at Britannica Online

- [3] More SciHi Blog articles related to Africa

- [4] Sir Henry Hamilton Johnston at Wikidata

- [5] Works by or about Harry Johnston at Internet Archive

- [6] Boyd, William (15 December 1991). “The Great African Land-Grab : THE SCRAMBLE FOR AFRICA; The White Man’s Conquest of the Dark Continent From 1876-1912, By Thomas Pakenham “. Los Angeles Times.

- [7] Timeline for Sir Henry Hamilton Johnston, via Wikidata

- [8] John Young, Flagler College HIS 363 Modern Africa: The Scramble for Africa, John Young @ youtube

- [9] Mary V. Fuller, “Gleanings“, in The American City, Vol. I, No. 3 (November 1903)

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #51 | Whewell's Ghost