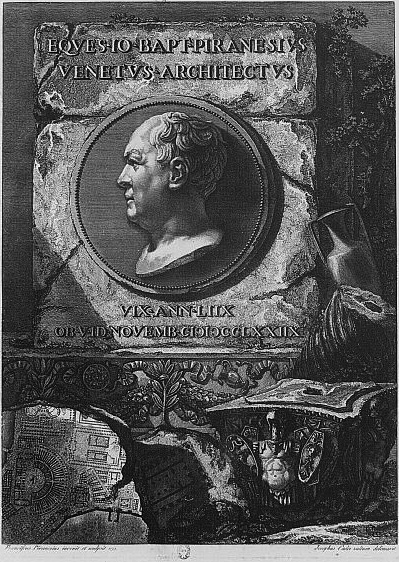

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720 – 1778)

On October 4, 1720, Italian Classical archaeologist, architect, and artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi was born. Piranesi is famous for his etchings of Rome and of fictitious and atmospheric “prisons” (Le Carceri d’Invenzione).

Giovanni Battista Piranesi – Family Background

Piranesi was born in Venice. He was the son of a stonemason who also worked as a construction manager. The first written document about Giovanni Battista Piranesi is his entry in the baptismal register of the parish of San Moisè in Venice, dated November 8, 1720. His brother Angelo taught Giovanni Battista Latin and the basics of ancient literature. He began his training as an architect at the Magistrato delle Acque with one of his mother’s brothers, Matteo Lucchesi, a Venetian civil engineer in charge of regulating the lagoon. After falling out with his uncle in a dispute, he continued his training with Giovanni Scalfarotto (1670-1764). In further training as a stage designer, he learned about the possibilities of stage decoration. This enabled him to intensively study the art of illusion and perspective. At this time in Venice – especially through Canaletto – the art of the veduta reached a peak.

Resurrecting Ancient Rome

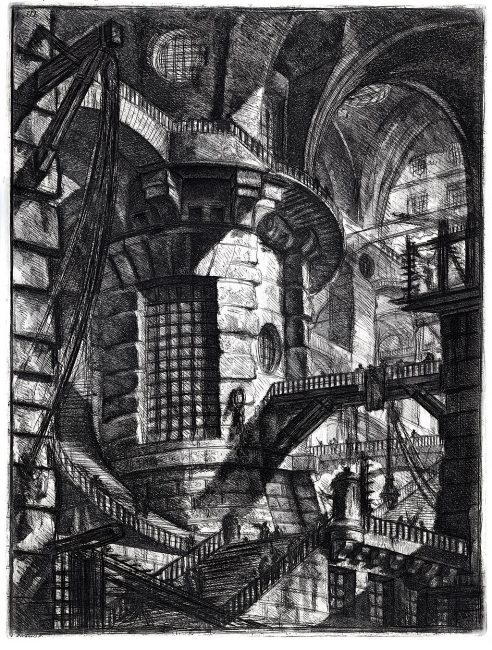

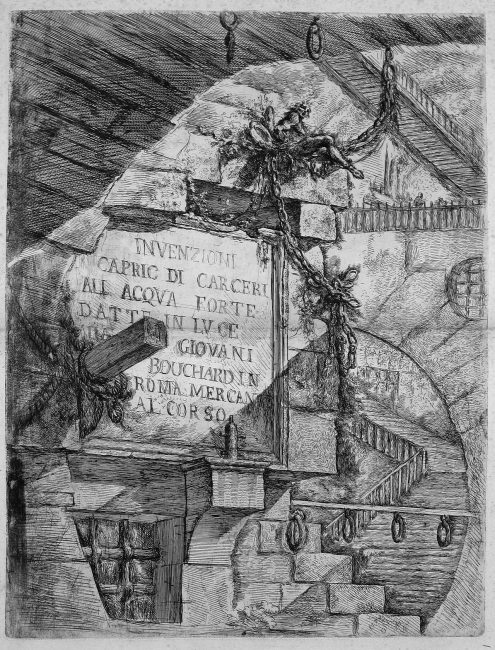

In 1740 Piranesi traveled to Rome as a draftsman in the entourage of Marco Foscarini, the Venetian envoy to the Holy See to study Roman architecture under the architects Nicola Salvi and Luigi Vanvitelli, the last representatives of a genuine Roman Baroque. Due to the economically desolate situation, it was not possible for him to work as an architect himself. Opportunities arose in the field of painting, especially through the beginning of Rome tourism. A year after his arrival in Rome, Piranesi began training with the veduta artist Giuseppe Vasi, who taught him the basics of etching and engraving. Piranesi soon fell out with Vasi, however, and broke off his training in his workshop. Impressed by the monumentality of the ancient ruins, he conceived the plan to resurrect ancient Rome in his drawings. In 1743 he published his first own work, Prima parte di Architettura e Prospettive – city views in a combination of engraving and etching. After losing himself in architectural fantasies (the famous series of Carceri of 1745/1760), he turned increasingly to Roman reality. The sixteen plates of the Carceri d’Invenzione di G. Battista Piranesi (Invented Dungeons of G. Battista Piranesi) are architectural fantasies inspired by stage sets, which take the sense of solitude, also perceptible in the vedute, combined with monumentality to the extreme. Together with fellows of the French Academy, he worked on a series of smaller views of Rome, which then appeared in 1745 as Varie Vedute di Roma Antica e Moderna.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Carceri-III-The round tower, 2nd version from 1761

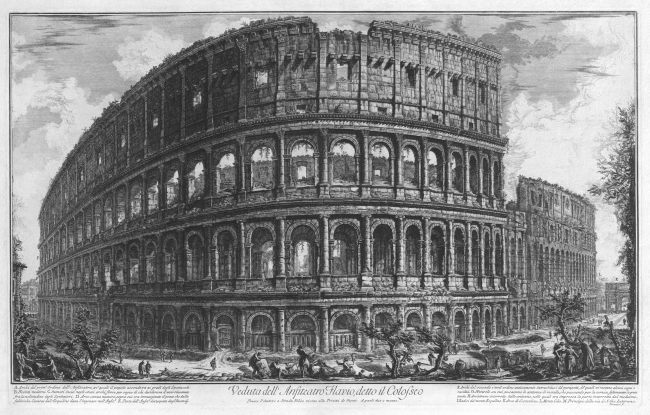

Vedute di Roma

From 1743 to 1747 he stayed mostly in Venice, where he also worked with Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Eventually he returned to Rome, where he opened a store on Via del Corso. Between 1748 and 1774 he created further series of vedute of baroque and ancient monuments of Rome, the Vedute di Roma, which – mostly illuminated by harsh sunlight – have a peculiarly monumental effect. These vedute also contain pictorial compositions in the manner of capriccios and shaped the image of the city for generations. In 1756 Piranesi explored and measured countless buildings of ancient Rome. The result was the publication of four volumes of views of Roman antiquities, the Antichità romane, to which he added precise ground plans and elevations in addition to expressive views. Thus the 36-year-old established his international fame as a leading archaeologist.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The Colosseum, etching, 1757

Roman seriousness and magnificenza against Greek frivolity

On February 24, 1757, he was admitted as an honorary member of the Society of Antiquaries of London and in 1761 to the Roman Accademia di San Luca. In 1761, the brisk sales of his vedute to tourists allowed him to set up his own workshop and print shop in Palazzo Tomati in Strada Felice, where he now published his works himself. With the arrival of Johann Joachim Winckelmann in Rome in 1755, the dispute between “Greeks” and “Romans” flared up.[1] Piranesi set Roman seriousness and Roman magnificenza against Greek “frivolity”. Piranesi devoted profound studies to Roman civil engineering, especially the Roman water supply system. In their functional aesthetics, he showed these functional buildings to be equal to sacred buildings.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Ruins of the large Baths,erroneously called the Sculpture Gallery at Tivoli, 1785

From Exterior to Interior Design

In 1763 Pope Clement XIII commissioned Piranesi to rebuild the choir of San Giovanni in Laterano. However, he did not get beyond the design stage. The following year, Piranesi was commissioned by Cardinal Giovanni Battista Rezzonico to redesign Santa Maria del Priorato. In 1767 the Pope knighted him. In the last ten years of his life, Piranesi turned to interior design and interior decoration. He was active as an antique dealer. With his works Diverse maniere d’adornare i cammini (1769) and Vasi, candelabri, cippi, sarcophagi, tripodi, luzerne ed ornamenti antichi (1778), he gained lasting influence on English villa architecture and their interiors, mediated through his friend, the architect Robert Adam. The two had become friends during Adam’s stay in Rome (1754-1758), with Piranesi’s evocative vedute leaving a lasting impression on the Scotsman. Adam’s overcoming of English Palladianism is hardly conceivable without Piranesi’s documentation of ancient Rome.

First plate in the first edition of Piranesi’s Le Carceri d’Invenzione (c. 1745-50)

Final Years

In his grandiose work of old age, the 20 etchings on the early Greek temples of Paestum, he, the “Roman,” testifies to a deep understanding of this austere, archaic art. Piranesi died in Rome in 1778 after a long illness. He was buried in the church of Santa Maria del Priorato. Three of his children, Laura, Francesco and Pietro Piranesi, were also well-known and successful artists.

Legacy

Piranesi achieved fame to this day above all with his Carceri d’Invenzione di G. Battista Piranesi. They influenced the new prison construction in Newgate in 1770, were used in copies to depict the horrors of the Bastille, and finally still left their mark in the film architecture of the 20th century. Much more extensive, however, were his documentations of ancient buildings and utilitarian objects in Rome and its environs, Cora and Paestum, which served artists throughout Europe as models for their own works. Piranesi also tapped Egyptian art as a source of inspiration for decorative arts. Thus he had a stimulating effect on the French Empire style.

John Marciari, The Imaginary and Eternal Prisons of Piranesi: First Friday Film Lecture, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Prophet of Modern Archaeology – Joachim Winckelmann, SciHi Blog

- [2] Lowe, Adam. “Messing About With Masterpieces: New Work by Giambattista Piranesi (1720-1778),” Art in Print Vol. 1 No. 1 (May–June 2011), p. 19

- [3] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Piranesi, Giovanni Battista“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [4] Focillon, Henri (1918). Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Essai de catalogue raisonné de son oeuvre. Paris.

- [5] Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- [6] Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Antichita Romanae (1748) (914 pages in 17 volumes; from BNF)

- [7] Giovanni Battista Piranesi, First state of Carceri (1750; 14 sketches in hi-res; digitized by Leyden university)

- [8] Wilton-Ely, J. (1978). The Mind and Art of Giovanni Battista Piranesi. London: Thames & Hudson.

- [9] Giovanni Battista Piranesi at Wikidata

- [10] John Marciari, The Imaginary and Eternal Prisons of Piranesi: First Friday Film Lecture, 2013, The San Diego Museum of Art @ youtube

- [11] Timeline for Giovanni Battista Piranesi, via Wikidata