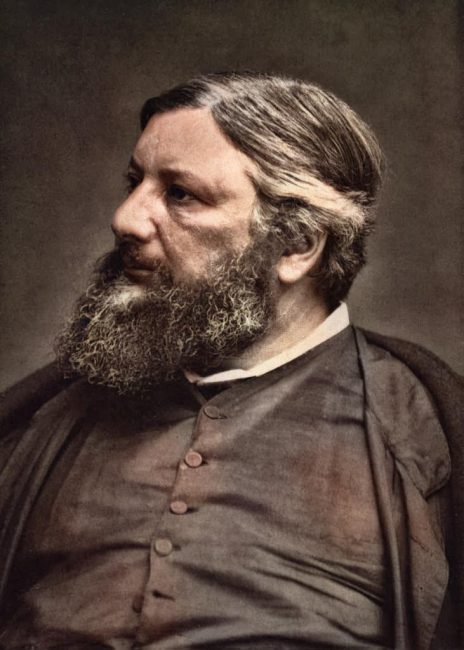

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877)

On June 10, 1819, French painter Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet was born, who led the Realism movement in 19th-century French painting. Committed to painting only what he could see, he rejected academic convention and the Romanticism of the previous generation of visual artists.

An Independent Spirit

Gustave Courbet was born in in Ornans, a village in the Franche-Comté in eastern France, to Régis and Sylvie Oudot Courbet, a prosperous farming family with anti-monarchical feelings. After attending both the Collège Royal and the college of fine arts at Besançon, he went to Paris in 1841, ostensibly to study law. He devoted himself more seriously, however, to studying the paintings of the masters in the Louvre and worked at the studio of Steuben and Hesse. An independent spirit, he soon left, preferring to develop his own style by studying the paintings of Spanish, Flemish and French masters in the Louvre, and painting copies of their work. He gained technical proficiency by copying the pictures of Diego Velázquez, José de Ribera, and other 17th-century Spanish painters.[2]

First Works and Influences

His first works were an Odalisque inspired by the writing of Victor Hugo [5] and a Lélia illustrating George Sand,[6] but he soon abandoned literary influences, choosing instead to base his paintings on observed reality. Among his paintings of the early 1840s are several self-portraits, Romantic in conception, in which the artist portrayed himself in various roles. These include Self-Portrait with Black Dog (c. 1842–44, accepted for exhibition at the 1844 Paris Salon), the theatrical Self-Portrait which is also known as Desperate Man (c. 1843–45), Lovers in the Countryside (1844, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon), The Sculptor (1845), and Man with a Pipe (1848–49, Musée Fabre, Montpellier).

Rejected by the Salon

When in the following years after his success with Black Dog the jury for the Salon thrice rejected his work because of its unconventional style and bold subject matter, he remained undaunted and continued to submit it. Trips to the Netherlands and Belgium in 1846–47 strengthened Courbet’s belief that painters should portray the life around them, as Rembrandt, Hals and other Dutch masters had. By 1848, he had gained supporters among the younger critics, the Neo-romantics and Realists, notably Champfleury. The Revolution of 1848 ushered in the Second Republic and a new liberal spirit that, for a brief while, greatly affected the arts. The Salon held its exhibition not in the Louvre itself but in the adjoining galleries of the Tuileries. [2]

Gustave Courbet, Self-portrait (The Desperate Man), c. 1843–45

First Salon Success

Courbet achieved his first Salon success in 1849 with his painting After Dinner at Ornans. The work, reminiscent of Chardin and Le Nain, earned Courbet a gold medal and was purchased by the state. The gold medal meant that his works would no longer require jury approval for exhibition at the Salon.

The Artist’s Own Experience

Courbet’s work belonged neither to the predominant Romantic nor Neoclassical schools. History painting, which the Paris Salon esteemed as a painter’s highest calling, did not interest him, for he believed that “the artists of one century [are] basically incapable of reproducing the aspect of a past or future century …” Instead, he maintained that the only possible source for living art is the artist’s own experience. Thus, he would find inspiration painting the life of peasants and workers.

The Proudest and Most Arrogant Man in France

Proclaiming himself as the “proudest and most arrogant man in France,” Gustave Courbet created a sensation at the Paris Salon of 1850–51 when he exhibited a group of paintings set in his native Ornans. These works, including The Stonebreakers (1849–50; now lost) and A Burial at Ornans (1849–50; Musèe d’Orsay, Paris) challenged convention by rendering scenes from daily life on the large scale previously reserved for history painting and in an emphatically realistic style. Confronted with the unvarnished realism of Courbet’s imagery, critics derided the ugliness of his figures and dismissed them as “peasants in their Sunday best.”[2] Previously, models had been used as actors in historical narratives, but in Burial at Ornans Courbet said he “painted the very people who had been present at the interment, all the townspeople“. The result is a realistic presentation of them.

Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans, 1849–50, oil on canvas

The Realist Approach

Eventually, the public grew more interested in the new Realist approach, and the lavish, decadent fantasy of Romanticism lost popularity. The artist well understood the importance of the painting. Courbet said of it, “The Burial at Ornans was in reality the burial of Romanticism.” Young Women from the Village, set in the outskirts of Ornans, generated further controversy at the Salon of 1852. Critics were nearly unanimous in reproaching Courbet for the “ugliness” of the three young women, for whom the artist’s sisters modeled, and for the disproportionately small scale of the cattle.[2]

The Painter’s Studio

In 1855, Courbet’s monumental canvas, The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up a Seven-Year Phase of My Artistic Life (Musée d’Orsay, Paris), an allegory of all the influences on Courbet’s artistic life, which are portrayed as human figures from all levels of society, was rejected by the jury of the Exposition Universelle. Courbet himself presides over all the figures with ingenuous conceit, working on a landscape and turning his back to a nude model, a symbolic representation of academic tradition.[1] Courbet retaliated by mounting his own exhibition in his Pavilion of Realism, built within sight of the official venue, where he displayed, among more than forty other works, The Painter’s Studio.[2] The enterprise failed; the painter Eugène Delacroix alone, in his journal, praised the audacity and talent of Courbet.[1]

Charles Baudelaire and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Courbet, an intimate of many writers and philosophers of his day, including the poet Charles Baudelaire and the social philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, became the leader of the new school of Realism, which in time prevailed over other contemporary movements. In 1856 Courbet visited Germany, where he was warmly welcomed by his fellow artists. Three years later, at the age of 40 and still working in defiance of severe criticism in his own country, he was the undisputed model for a new generation of painters who had turned away from the traditional schools of painting.[1]

Courbet worked in all genres. A lover of women, he glorified the female nude in paintings of stunning warmth and sensuality. He executed admirable portraits, but above all he celebrated the Franche-Comté, the forests, springs, rocks, and cliffs of which were immortalized by his vision.

Franco-German War and the Commune

The Franco-German War broke out in 1870, the Second Empire collapsed, and the Third Republic was proclaimed. On March 18, 1871, the republican Paris Commune was established to fight the Germans in France as well as to fight the Army of Versailles, which had remained loyal to Napoleon III and had concluded an armistice with the Germans that the members of the Commune judged to be dishonourable.[1] Courbet made a proposal that later came back to haunt him. He wrote a letter to the Government of National Defense, proposing that the column in the Place Vendôme, erected by the Napoleon I to honour the victories of the French Army, be taken down. The Commune had voted to destroy the column in the Place Vendôme commemorating the Grand Army of Napoleon Bonaparte, and it carried out the decision on May 16. But on May 28 the Commune was crushed by the Army of Versailles, and on June 7 Courbet was arrested at the home of a friend. Because he was thought to have been responsible for the demolition of the column, he was brought before a military court. As he had often made known his disgust of the militarism represented by the monument, he was charged with having been the instigator, although he had in no way participated in its destruction.[1]

Later Years

Courbet finished his prison sentence on 2 March 1872, but his problems caused by the destruction of the Vendôme Column were still not over. In 1873, the newly elected president of the Republic, Patrice Mac-Mahon, announced plans to rebuild the column, with the cost to be paid by Courbet. Unable to pay, Courbet went into a self-imposed exile in Switzerland to avoid bankruptcy. On 4 May 1877, Courbet was told the estimated cost of reconstructing the Vendôme Column; 323,091 francs and 68 centimes. He was given the option paying the fine in yearly installments of 10,000 francs for the next 33 years, until his 91st birthday. On 31 December 1877, a day before the first installment was due, Courbet died, aged 58.

Travis Lee Clarke, Lecture 10 French Realism, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Gustave Courbet, French painter, at Britannica Online

- [2] Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), at Metmuseum.de

- [3] The Paris Salon de Refusés, SciHi Blog, May 15, 2016.

- [4] Charles Baudelaire and the Flowers of Evil, SciHi Blog

- [5] Nothing is Stronger than an Idea whose Time has come – The Life of Victor Hugo, SciHi Blog

- [6] The Scandalous Love Affairs of George Sand, SciHi Blog

- [5] Gustave Courbet at Wikidata

- [6] Travis Lee Clarke, Lecture 10 French Realism, ARTH2720 Art History from the Renaissance, Art History with Travis Lee Clark @ youtube

- [7] Griffiths, Harriet & Alister Mill, Courbet’s early Salon exhibition record, Database of Salon Artists, 1827–1850

- [8] Chu, Petra ten Doesschate. The Most Arrogant Man in France: Gustave Courbet and the Nineteenth-Century Media Culture. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007)

- [9] Timeline for Gustave Courbet, via Wikidata