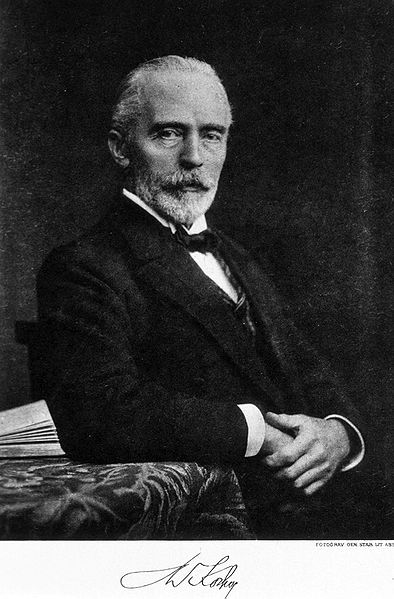

Emil Theodor Kocher (1841-1917)

On August 25, 1841, Swiss physician and Nobel Laureate Emil Theodor Kocher was born. Kocher received the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work in the physiology, pathology and surgery of the thyroid. Among his many accomplishments are the introduction and promotion of aseptic surgery and scientific methods in surgery, specifically reducing the mortality of thyroidectomies below 1% in his operations.

Emil Theodor Kocher – Early Years

Born in Bern, Switzerland, Theodor Kocher was the second son of overall six children of Jakob Alexander Kocher, railway engineer and later chief engineer for street and water of the Canton of Bern, and his wife Maria Kocher (née Wermuth). He graduated from high school in Burgdorf with the Swiss matura in 1858 and studied medicine at the University of Bern, where he passed his state examination in 1865 and his doctorate in 1866, with his dissertation about “Behandlung der croupösen Pneumonie mit Veratrum-Präparaten” (The treatment of croupous pneumonia with Veratrum preparations) under Anton Biermer. Before traveling across Europe, Kocher followed his mentor Biermer to Zurich, where Theodor Billroth was director of the hospital and influenced Kocher significantly. Theodor Kocher traveled to Berlin, where he studied under Bernhard von Langenbeck and later moved on to London where he first met Jonathan Hutchinson and then worked for Henry Thompson and John Erichsen. In Paris, he met Auguste Nélaton, Auguste Verneuil and Louis Pasteur.[3]

Academic Career

Upon returning to Bern, Kocher prepared for his habilitation and became assistant to Georg Lücke who left Bern in 1872 to become professor in Strasbourg. Even though it was Franz König’s turn to follow Lücke, the pressure from students, the media, and befriended scientists resulted in the announcement of Kocher as the successor of Lücke as Ordinary Professor of Surgery and Director of the University Surgical Clinic at the Inselspital on 16 March 1872. In the 45 years he served as professor at the university, he oversaw the re-building of the famous Bernese Inselspital, published 249 scholarly articles and books, trained numerous medical doctors and treated thousands of patients. He made major contributions to the fields of applied surgery, neurosurgery and, especially, thyroid surgery and endocrinology. For his work he received, among other honors, the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

The Antiseptic Method

Theodor Kocher began his scientific work with a series of articles on hemostasis in twisting arteries. When he began his surgical career, a shift was taking place between the time-honored septic to the novel antiseptic methods of treatment. It is unclear whether Kocher directly knew Joseph Lister, [4] who pioneered the antiseptic (using chemical means to kill bacteria) method, but Kocher was in correspondence with him. Kocher had recognized the importance of aseptic techniques early on, introducing them to his peers at a time when this was considered revolutionary. In a hospital report from 1868, he attributed the lower mortality directly to the “antiseptic Lister’s wound bandaging method” and he could later as director of the clinic order strict adherence to the antiseptic method.

Further Achievements

In addition to wound and fracture treatment, surgery of the internal organs represented a significant part of his work, such as surgery for gastric and intestinal diseases. The Kocher maneuver, which can be used to free the duodenum from adhesions, is named after him. Likewise, he developed a number of surgical instruments, not least the Kocher clamp named after him, which is still used today. In June 1878 Kocher performed the first successful two-stage cholecystostomy, as was also used by Franz König in Göttingen in 1882.

Advances in Thyroid Surgery

Kocher is probably best known for his achievements in thyroid surgery. Back then, it was mostly performed as treatment of goitre with a thyroidectomy when possible. The very risky procedure was considered as one of the most dangerous operations. Some estimates put the mortality of thyroidectomy as high as 75% in 1872. However, through application of modern surgical methods, such as antiseptic wound treatment and minimizing blood loss, and the famous slow and precise style of Kocher, he managed to reduce the mortality of this operation from an already low 13% to less than 0.5% by 1912.

Side Effects

Later on, Kocher and further contemporary scientists discovered that the complete removal of the thyroid could lead to cretinism as part of a hormone issue. The phenomena was reported to Kocher first in 1874 by the general practitioner August Fetscherin and later in 1882 by Jacques-Louis Reverdin together with his assistant Auguste Reverdin. Ironically, it was his precise surgery that allowed Kocher to remove the thyroid gland almost completely and led to the severe side effects of cretinism. Theodor Kocher published his findings, that a complete removal of the thyroid gland was not advisable, in 1883. The lecture was held before the German Society of Surgery and the published article was titled “Ueber Kropfexstirpation und ihre Folgen” (About Thyroidectomies and their consequences).[12,13] Jacques-Louis Reverdin had already published his findings in 1882, still Kocher never acknowledged Reverdin’s priority in this discovery. In the long run however, these observations contributed to a more complete understanding of thyroid function and were one of the early hints of a connection between the thyroid and congenital cretinism. These findings finally enabled thyroid hormone replacement therapies for a variety of thyroid related diseases. Kocher’s thyroid research earned Kocher the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the physiology, pathology, and surgery of the thyroid gland.

Death

On the evening of 23 July 1917, he was called into the Inselspital for an emergency. Kocher executed the surgery but afterwards felt unwell and went to bed, working on scientific notes. He then fell unconscious and died on 27 July 1917.

Peter Kopp, The Legacy of Theodor Kocher World Congress on Thyroid Cancer 2017, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Emil Theodor Kocher at Britannica

- [2] Emil Theodor Kocher at the Nobel Prize Page

- [3] Louis Pasteur – the Father of Medical Microbiology, SciHi Blog

- [4] Dr. Joseph Lister and the use of Carbolic Acid as Disinfectant, SciHi blog

- [5] Emil Theodor Kocher at Wikidata

- [6] Works by or about Emil Theodor Kocher at Internet Archive

- [7] Edgar Bonjour: Kocher, Theodor. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1, S. 282 f.

- [8] Peter Kopp, The Legacy of Theodor Kocher World Congress on Thyroid Cancer 2017, World Congress on Thyroid Cancer @ youtube

- [9] Emil Theodor Kocher, Chiruigische Operationslehre (1894; Eng. trans. as Textbook of Operative Surgery, 2 vols., 1911)

- [10] Koelbing, Huldrych M.F. “Kocher, Theodor im Historischen Lexikon der Schweis”. Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz

- [11] Tan, SY.; Shigaki, D. (September 2008). “Emil Theodor Kocher (1841–1917): thyroid surgeon and Nobel laureate” (PDF). Singapore Med J. 49 (9): 662–663

- [12] Ulrich, Tröhler. “Towards endocrinology: Theodor Kocher’s 1883 account of the unexpected effects of total ablation of the thyroid”. JLL Bulletin: Commentaries on the history of treatment evaluation www.jameslindlibrary.org.

- [13] Kocher, Theodor. “Ueber Kropfexstirpation und ihre Folgen”. Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie. 29: 254–337.

- [14] Timeline of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine, via Wikidata