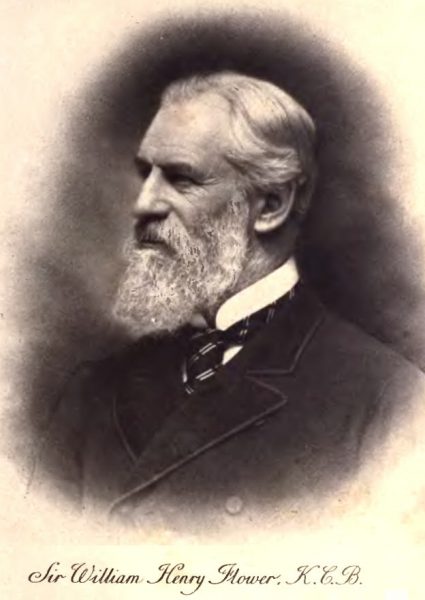

William Henry Flower (1831 – 1899)

On November 30, 1831, English comparative anatomist and surgeon William Henry Flower was born. Flower became a leading authority on mammals, and especially on the primate brain. He supported Thomas Henry Huxley in an important controversy with Richard Owen [3] about the human brain, and eventually succeeded Owen as Director of the Natural History Museum.

“[There is an] immense advantage to be gained by ample space and appropriate surroundings in aiding the formation of a just idea of the beauty and interest of each specimen… Nothing detracts so much from the enjoyment … from a visit to a museum as the overcrowding of the specimens exhibited.”

— Sir William Henry Flower, Essays on Museums (1898), 33.

William Henry Flower – Early Years

William Henry Flower was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, UK, the second son of the brewery owner Edward Fordham Flower (1805-1883) and his wife Celina Greaves (1804-1884). In 1849 Flower was enrolled at University College London to study zoology, where he studied physiology with William Sharpey. In March 1852 Flower read his first paper before the Zoological Society, of which he was a Fellow. In the same year he began his medical training at the hospital of Middlesex. In 1851 he passed the examinations for Baccalaureus Artium at University College. March 27, 1854, Flower became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons. A month later, on April 28, 1854, he joined the British Army Medical Department and served as an assistant surgeon with the 63rd Foot Regiment during the Crimean War. Due to health problems, however, he left the service already on May 1, 1855, and returned to England. In May 1857, Flower passed the examinations for admission as a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Huxley, Owen, and the Human Brain

Flower had long been interested in natural history, and he later decided to move his career in that direction, probably under the influence of Thomas Henry Huxley, who was also a comparative anatomist, and Fullerian Professor at the Royal Institution at the time. Flower further became associated with Huxley’s controversy with Richard Owen concerning the human brain. Owen had erroneously said that the human brain had structures that were not present in other mammals, and separated man off into a Sub-Class of its own instead of a genus in the primates. Huxley contradicted this in a debate at the BA meeting in 1860, and promised a demonstration in due course. Huxley consulted Flower on the matter and over the years, Flower published papers on the brains of four species of monkey, and acted as Huxley’s partner in demonstrations at subsequent BA meetings. He published papers on the brains of four species of monkey, and at the 1862 meeting of the British Association in Cambridge, after Owen read a paper repeating his claims, stood up saying “I happen to have in my pocket a monkey’s brain” and produced the object in question.

Lectures on Mammalia

In 1870 he became Hunterian Professor of Comparative Anatomy in succession to Huxley and commenced a series of lectures that ran for fourteen years, all on aspects of the Mammalia. The essence was published in his books of 1870 and 1891. He was President of the Zoological Society of London from 1879 to 1899. In 1882 he was awarded the Royal Medal of the Royal Society.

Later Years

In 1884, on the retirement of Sir Richard Owen, Flower was appointed to the directorship of the Natural History departments of the British Museum in South Kensington. In addition to his role as Director, Flower also took over from Albert Günther, the ornithologist, as Keeper of Zoology in 1895, remaining so until his retirement in 1898. Apart from his continuing interest in primates, Flower became an expert on the Cetacea. He carried out dissections, went out on whaling boats, arranged whale exhibits in the Museum in South Kensington, and studied the new discoveries of whale fossils. His publications were all bar a few on mammals; he was not a field biologist, nor a student of the other vertebrate groups, at any rate in his adult life. He wrote forty articles for the 9th edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica, every one on a group of mammals. Flower was an effective Director of the natural history departments of the British Museum, balancing the competing and conflicting needs of the staff, the public, the other professional naturalists, the Trustees and the Principal Librarian.

Flower as a Public Figure

He became a public figure, his lectures being crowded and his views influential. In a study of deliberate deformation of the human body in various cultures, he included corsets and high heels, illustrating the effects with pictures of distorted female skeletons. Horrified at the widespread slaughter of birds to provide feathers for fashionable hats, he said of the egret: “one of the most beautiful of birds is being swept off the face of the earth under circumstances of peculiar cruelty, to minister to a passing fashion.” Which led Beatrix Potter to write: “I wonder what Sir W Flower’s speciality is besides ladies’ bonnets.”

Illness and overwork led Flower to take retirement from the Natural History Museum in August 1898 and he died at his home in South Kensington on I July 1899, aged 67.

Nancy Kanwisher, 1. Introduction to the Human Brain, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] An introduction to the osteology of the mammalia

- [2] William Henry Flower at Britannica

- [3] Sir Richard Owen and the Interpretation of Fossils, SciHi Blog

- [4] Kate (23 September 2004). “Flower, Sir William Henry (1831–1899)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- [5] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Flower, Sir William Henry“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 553.

- [6] Cornish, Charles J. (1904). Sir William Henry Flower KCB: A Personal Memoir. London: Macmillan.

- [7] Works by or about William Henry Flower at Internet Archive

- [8] Flower, William Henry – Biodiversity Heritage Library

- [9] William Henry Flower at Wikidata

- [10] Nancy Kanwisher, 1. Introduction to the Human Brain, MIT 9.13 The Human Brain, Spring 2019, MIT OpenCourseWare @ youtube

- [11] Timeline of Evolutionary Biologists, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #16 | Whewell's Ghost