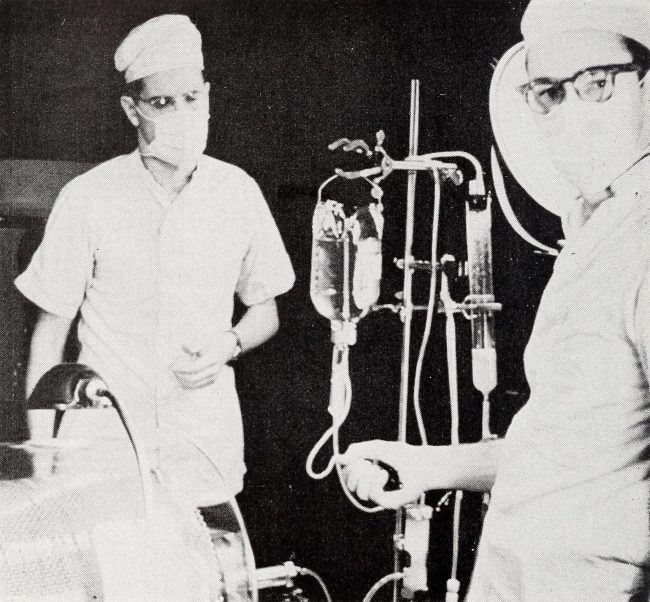

Artificial kidney (Kolff type) in operation at the Renal Insufficiency Center (Korea)

On February 14, 1911, Dutch-American physician and biomedical engineer Willem Johan Kolff was born. Kolff is considered to be the Father of Artificial Organs, and is regarded as one of the most important physicians of the 20th century. He made his major discoveries in the field of dialysis for kidney failure during the Second World War.

Education and first Research

Willem Johan Kolff was born in Leiden, Netherlands, as the eldest of a family of 5 boys. His father was a doctor. When he took over the management of a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients, Willem moved to Beekbergen at the age of six. From 1930-1937, Willem Kolff studied medicine in his hometown at Leiden University, and continued as a resident in internal medicine at Groningen University. In 1938, one of his first patients there was a 22-year-old man who was slowly dying of kidney failure. He reasoned that if he could find a way to remove the toxic waste products that build up in the blood of such patients, he could keep them alive until their kidneys rebounded.[1] This prompted Kolff to perform research on artificial renal function replacement. For his first experiment, Kolff filled sausage casings with blood, expelled the air, added a kidney waste product called urea and agitated the contraption in a bath of salt water. The casings were semipermeable. Small molecules of urea could pass through the membrane, while larger blood molecules might not. In short time, all the urea had moved into the salt water. The concept for building an artificial kidney was born. But it soon went underground.[1]

The First Functional Articifial Kidney

During his residency in 1940, Kolff organized the first blood bank in Europe in a small hospital in Kampen, on the Zuider Zee (now called the Ijsselmeer) and continued his work on the artificial kidney. During World War II, he was in Kampen, where he was active in the resistance against the German occupation. Simultaneously, Kolff developed the first functioning artificial kidney. Actually, he cobbled together his rotating drum artificial kidney from miscellaneous available parts including bed slats, a bathtub, and sundry tubing connectors of considerable sophistication. In the artificial kidney uremic blood is circulated through tubing that itself is moving through a stationary noncirculating dialysis bath. The membrane area employed was 2 to 2.5 square meters, depending on the spacing of the spiral windings of the cellulosic tubing around the drum. Priming the blood path required 1.5–2.0 units of blood from the blood bank. There was no formal blood pump — the rotation of the drum along with gravity moved the blood out of the patient and then back.[3] Kolff treated his first patient in 1943, and in 1945 he was able to save a patient’s life with hemodialysis treatment. In 1946 he obtained a PhD degree summa cum laude at University of Groningen on the subject. It marks the start of a treatment that has saved the lives of millions of acute or chronic renal failure patients ever since.

Replica of the drum kidney from Willem Kolff, I, Grossw, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Seeking Opportunities in the US

When the war ended, Kolff donated his artificial kidneys to other institutions to spread familiarity with the technology. In Europe, Kolff sent machines to London, Amsterdam, and Poland. The first human dialysis in the U.S. took place at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City in 1948. In 1950, Kolff left the Netherlands to seek opportunities in the US. At the Cleveland Clinic, he was involved in the development of heart-lung machines to maintain heart and pulmonary function during cardiac surgery. He also improved on his dialysis machine. At Brigham and Women’s Hospital he developed the first production artificial kidney, the Kolff Brigham Artificial Kidney, and later the Travenol Twin-Coil Artificial Kidney. But in 1956 – together with Bruno Watschinger from Linz – he developed the twin coil kidney “Twin Coil” as the first commercially available dialyzer for single use and used it in 1967 in Maytag washing machines and even in surplus NASA rocket tips as an “artificial kidney”.

Later Life

Kolff became head of the University of Utah’s Division of Artificial Organs and Institute for Biomedical Engineering in 1967, where he was involved in the development of the artificial heart together with his fellow Robert Jarvik, the first of which, the Jarvik-7, was implanted in 1982 in the now famous patient Barney Clark.[3] In 1976 Kolff became a corresponding member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Kolff was a founding member of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs and was the recipient of more than 120 awards, notably the Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award, which he shared in 2002.[2]

Willem Johan Kolff died on February 11, 2009, aged 97.

Printing a human kidney – Anthony Atala, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] S. Blakeslee, Willem Kolff, Doctor Who Invented Kidney and Heart Machines, Dies at 97, The New York Times, Feb 12, 2009.

- [2] Wilhelm Johan Kolff, American Physician, Britannica Online

- [3] Lee W. Henderson, A Tribute to Willem Johan Kolff, M.D., 1912–2009, JASN May 2009 vol. 20 no. 5 923-924.

- [4] Willem Kolff at Wikidata

- [5] Obituary for Willem Kolff in the Telegraph newspaper

- [6] Printing a human kidney – Anthony Atala, TED-Ed @ youtube

- [7] Timeline of Nephrologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata