Hardy–Weinberg principle for two alleles

On January 13, 1908, German physician and obstetrician-gynecologist Wilhelm Weinberg delivered an exposition of his ideas on the principle of genetic equilibrium in a lecture before the Verein für vaterländische Naturkunde in Württemberg. He developed the idea of genetic equilibrium independently of British mathematician G. H. Hardy.[4]

Wilhelm Weinberg – Early Years

Wilhelm Weinberg was born in Stuttgart, Kingdom of Württemberg (today Germany). His father Julius Weinberg, a merchant, had Jewish roots, but he himself, like his mother Maria Magdalena Humbert, was baptized Protestant. He studied medicine at the Universities of Berlin, Tübingen, and Munich, Germany. He returned to Stuttgart in 1889, where he remained running a large practice as a gynecologist and obstetrician. He is known to have been a physician to the poor and delivered around 3500 babies in his life. Still, he managed to write over 160 scientific papers as well as numerous reviews and comments in addition. The fact that his recognition outside of the German speaking area was so little, was according to contemporary scientists highly noticeable in his writings. His criticism was often very personal and his reviews very argumentative.

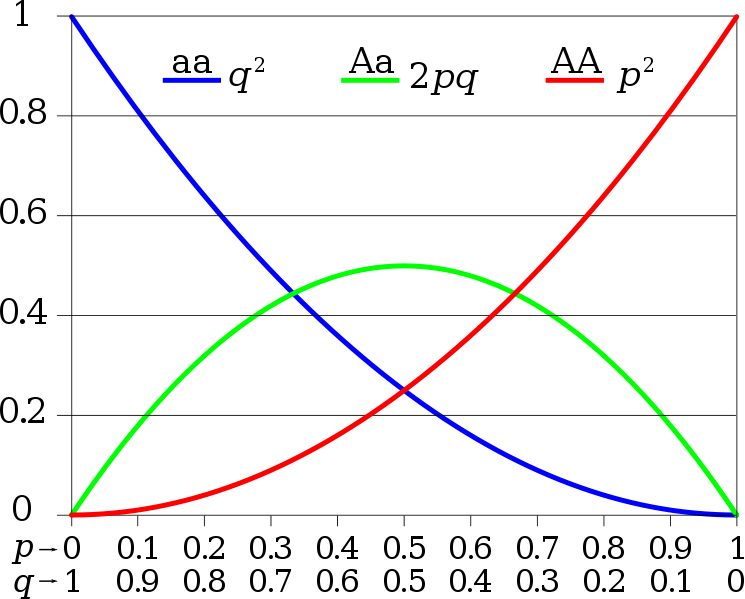

Hardy-Weinberg Principle

However, the scientist is mainly known for his contributions to the Hardy–Weinberg principle. It is also known as the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, model, theorem, or law. It states that allele and genotype frequencies in a population will remain constant from generation to generation in the absence of other evolutionary influences. These influences include non-random mating, mutation, selection, genetic drift, gene flow and meiotic drive. Because one or more of these influences are typically present in real populations, the Hardy–Weinberg principle describes an ideal condition against which the effects of these influences can be analyzed. The principle was developed by the British mathematician Godfrey Harold Hardy and Weinberg independently. Weinberg’s work was published in a lecture at the Society for the Natural History of the Fatherland in Württemberg, which was six months before the publishing of Hardy’s paper in English.

Since Weinberg’s scientific work was published in German, it remained completely unrecognized for over 35 years. Curt Stern was a contemporary German geneticist and he immigrated to the United States just before World War II. When he found out, that the achievement of both scientists was named “Hardy’s law” or “Hardy’s formula”, he pointed out Weinberg’s work in a scientific paper. Another reason, why Weinberg’s achievement was ignored for so many years may be the fact that it was written very difficultly, even for native speakers. Still, he used only elementary mathematics and avoided calculus as much as he could.

Further Achievements

Wilhelm Weinberg also pioneered in the studies of twins. He developed techniques to analyze the phenotypic variation that partitioned this variance into genetic and environmental components. Weinberg recognized that ascertainment bias was affecting many of his calculations, and he produced methods to correct for it. Weinberg observed that proportions of homozygotes in familial studies of classic autosomal recessive genetic diseases generally exceed the expected Mendelian ratio of 1:4, and he explained how this is the result of ascertainment bias. He discovered the answer to several seeming paradoxes caused by ascertainment bias and he recognized that ascertainment was responsible for a phenomenon known as anticipation, the tendency for a genetic disease to manifest earlier in life and with increased severity in later generations.

Epidemiological Cohort Study

In 1910 Wilhelm Weinberg founded the Stuttgart branch of the Society for Racial Hygiene, of which he was chairman for a long time. During this period, Weinberg conducted a large-scale study of children of parents who had died of tuberculosis between 1873 and 1902 and compared their health status with that of their peers whose parents had not died of tuberculosis. Published under the title The Children of the Tuberculous in 1913, the study is considered a scientifically exemplary epidemiological cohort study of the first half of the twentieth century.[9,10]

In 1931, a few years before his death, Wilhelm Weinberg moved for financial reasons to Tübingen, where he died in 1937. He passed away on November 27, 1937.

Manolis Kellis, 6.047/6.878 Lecture 13 – Population Genetics (Fall 2020), [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Hardy, Weinberg and Language Impediments. James F. Crow, 1999 [PDF]

- [2] Weinberg, W., 1908: Über den Nachweis der Vererbung beim Menschen, Jahreshefte des Vereins für Vaterländische Naturkunde in Württemberg 64: 369-82.

- [3] Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium Calculator

- [4] G. H. Hardy and the aesthetics of Mathematics, SciHi Blog, December 1, 2016.

- [5] Crick and Watson decipher the DNA, SciHi Blog

- [6] The Avery-McLeod-McCarthy Experiment, SciHi Blog

- [7] Max Delbrück and the Genes, SciHi Blog

- [8] Wilhelm Weinberg at Wikidata

- [9] Wilhelm Weinberg, Die Kinder der Tuberkulösen. Hirzel, Leipzig 1913.

- [10] Alfredo Morabia, Regina Guthold: Wilhelm Weinberg’s 1913 Large Retrospective Cohort Study: a Rediscovery. In: American Journal of Epidemiology. Bd. 165, Nr. 7, 2007, S. 727–733

- [11] Crow, James F. (1999). “Hardy, Weinberg and language impediments”. Genetics. 152 (3): 821–825.

- [12] Manolis Kellis, 6.047/6.878 Lecture 13 – Population Genetics (Fall 2020), Manolis Kellis @ youtube

- [13] Timeline of Population Geneticists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #27 | Whewell's Ghost