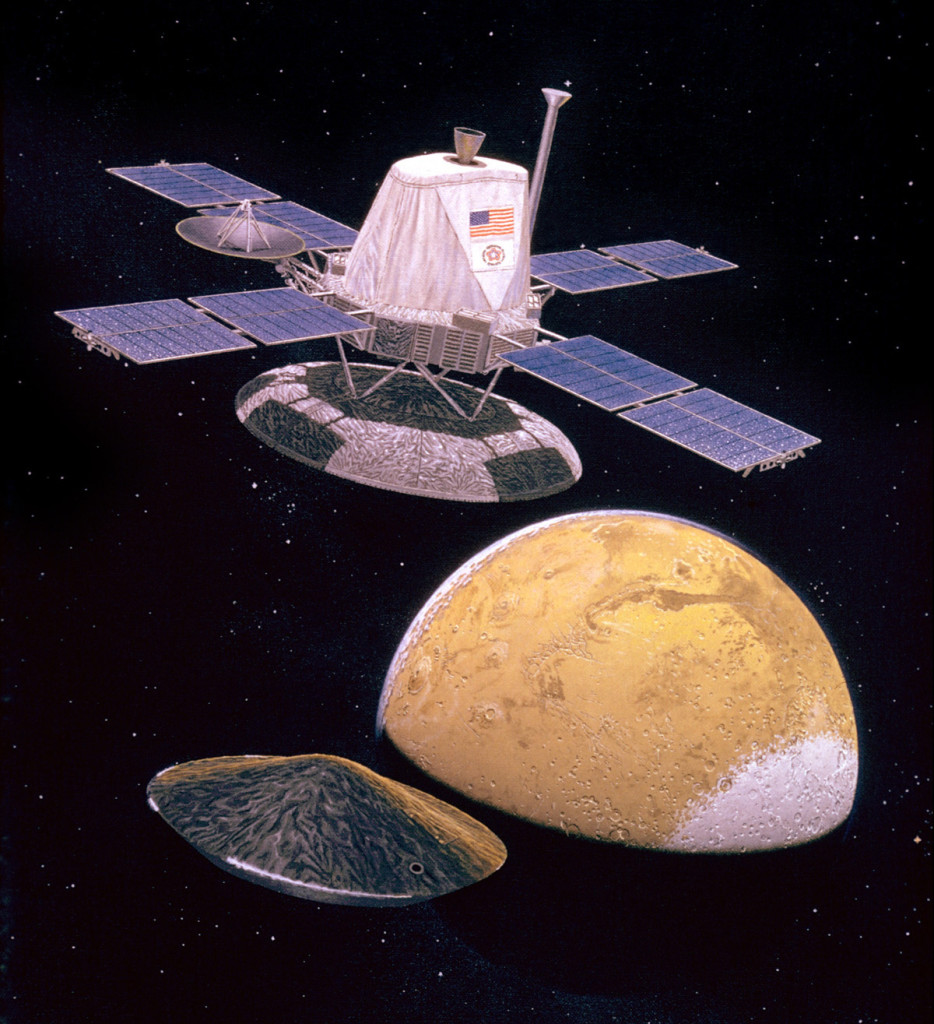

Viking Orbiter releasing the lander

On August 20, 1975, NASA spacecraft Viking 1 was launched and sent to Mars. The Viking program was was the most expensive and ambitious, but also highly successful mission ever sent to Mars. The Viking spacecraft was composed of two main parts: an orbiter designed to photograph the surface of Mars from orbit, and a lander designed to study the planet from the surface. Moreover, I remember the exciting messages in the news as a child, when the Viking lander began its descent to the surface and when the first pictures from the Mars surface came back to Earth. Back then in the 1970s, it seemed only to be a matter of a few years until the first manned Mars mission.

The Exploration of Mars

The exploration of Mars began in 1960, when the Soviets launched a series of probes including the intended first flybys and hard (impact) landing. The first successful fly-by of Mars was on July 14–15, 1965, by NASA‘s Mariner 4. On November 14, 1971 Mariner 9 became the first space probe to orbit another planet when it entered into orbit around Mars. The amount of data returned by probes increased dramatically as technology improved. It was also the Soviet‘s who succeeded first to send a probe safely to the Mars surface: Mars 2 lander on November 27, 1971, which failed during descent and Mars 3 lander on December 2, 1971, wwhose communication system failed about twenty seconds after the first Martian soft landing. Mars 6 failed during descent but did return some corrupted atmospheric data in 1974.

NASA’s Viking Project was the first U.S. mission to land a spacecraft safely on the surface of Mars and return images of the surface. In fact, two identical spacecraft, Viking 1 and Viking 2, each consisting of a lander and an orbiter, were built. The primary mission objectives were to obtain high resolution images of the Martian surface, characterize the structure and composition of the atmosphere and surface, and search for evidence of life. Each orbiter-lander pair flew together and entered Mars orbit; the landers then separated and descended to the planet’s surface. Following launch, Viking 1 made its 10-month cruise and arrived at Mars on June 19, 1976. The first month of orbit was devoted to imaging the surface to find appropriate landing sites for the Viking Landers.

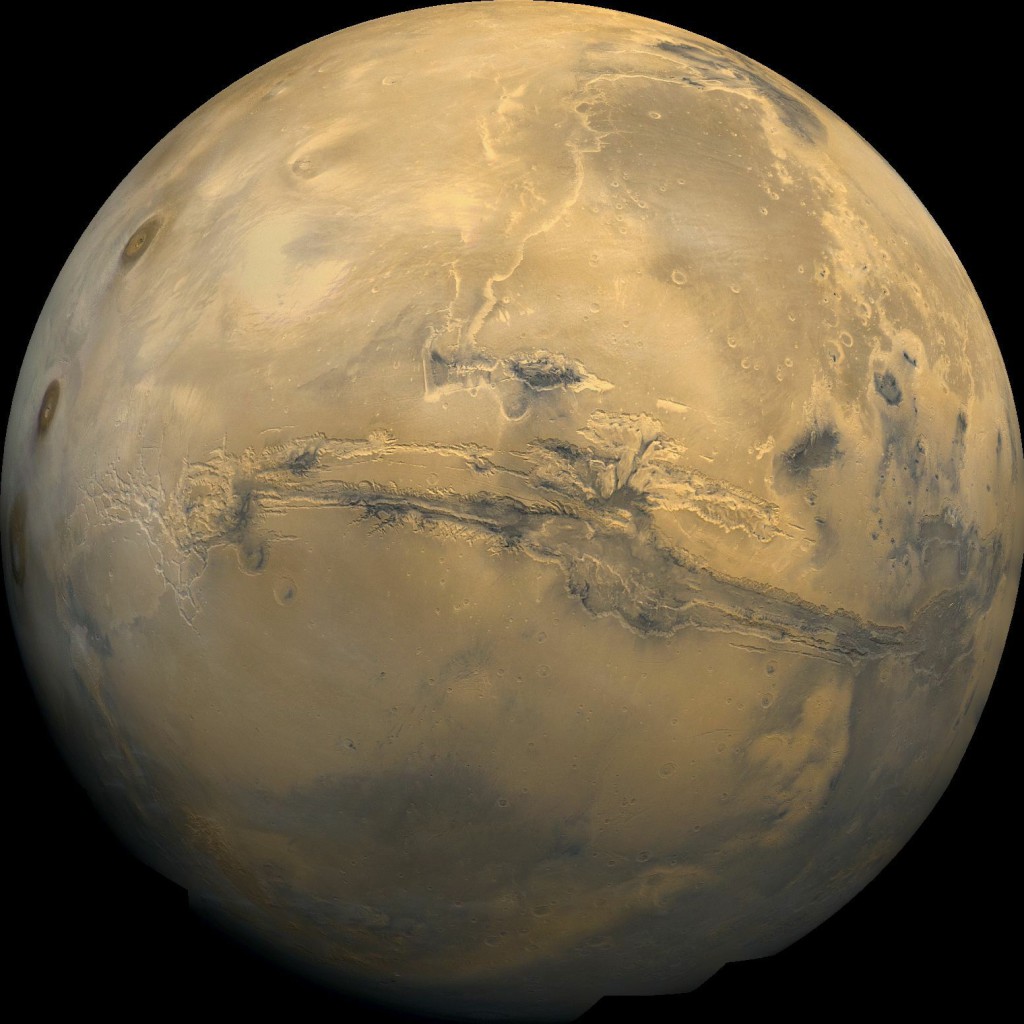

Mars image mosaic from the Viking 1 orbiter

Viking 1 Orbiter

By discovering many geological forms that are typically formed from large amounts of water, the images from the orbiters caused a revolution in our ideas about water on Mars. Huge river valleys were found in many areas. They showed that floods of water broke through dams, carved deep valleys, eroded grooves into bedrock, and travelled thousands of kilometers. The results from the Viking experiments give our most complete view of Mars to date. Volcanoes, lava plains, immense canyons, cratered areas, wind-formed features, and evidence of surface water are apparent in the Orbiter images. The planet appears to be divisible into two main regions, northern low plains and southern cratered highlands. Superimposed on these regions are the Tharsis and Elysium bulges, which are high-standing volcanic areas, and Valles Marineris, a system of giant canyons near the equator.[1]

Viking 1 Lander

Landing on Mars was planned for July 4, 1976, the United States Bicentennial, but imaging of the primary landing site showed it was too rough for a safe landing. The landing was delayed until a safer site was found. The lander separated from the orbiter on July 20 08:51 UTC and landed at 11:53:06 UTC at Chryse Planitia. At an altitude of about 6 kilometers and traveling at a velocity of 900 kilometers per hour, the parachute deployed, the aeroshell released and the lander’s legs unfolded. At an altitude of about 1.5 kilometers, the lander activated its three retro-engines and was released from the parachute. The lander then immediately used the rockets to slow and control its powered descent, with a soft landing on the surface of Mars. It was the first attempt by the United States at landing on Mars.

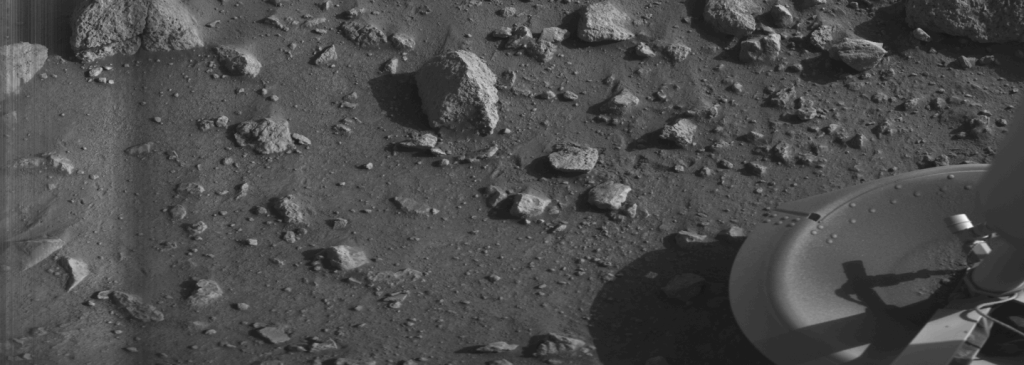

First “clear” image ever transmitted from the surface of Mars – shows rocks near the Viking 1 Lander (July 20, 1976).

The Viking landers conducted biological experiments designed to detect life in the Martian soil (if it existed). Viking 1 performed the first Martian soil sample using its robotic arm and a special biological laboratory. One experiment turned positive for the detection of metabolism (current life), but based on the results of the other two experiments that failed to reveal any organic molecules in the soil, most scientists became convinced that the positive results were likely caused by non-biological chemical reactions from highly oxidizing soil conditions.[1] According to scientists, Mars is self-sterilizing. They believe the combination of solar ultraviolet radiation that saturates the surface, the extreme dryness of the soil and the oxidizing nature of the soil chemistry prevent the formation of living organisms in the Martian soil.[2]

Mission End

Each Viking mission was only supposed to last 90 days after landing, but the landers and orbiters actually lasted for years. As for the Viking 1 lander, it sent back its first image of the surface just moments after landing, and took thousands more for scientists to process over its lifetime. Besides a seismometer experiment that refused to deploy properly, and early problems with a sampler pin, the experiments on board the lander remained healthy through its last day of transmissions on Nov. 13, 1982.[4]

Carl Sagan, Mars after Viking [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Viking Mission to Mars at NASA

- [2] Viking 1 and Viking 2 at NASA

- [3] Viking 1 at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- [4] Elizabeth Howell: Viking 1: First U.S. Lander on Mars, at Space.com

- [5] Lost on Mars – The Beagle 2 Mission, SciHi Blog

- [6] Allan Hills 84001 and Life on Mars, SciHi Blog

- [7] Giovanni Schiaparelli and the Martian Canals, SciHi Blog

- [8] Mariner 4 and the First Pictures from Mars, SciHi Blog

- [9] Viking 1 at Wikidata

- [10] Carl Sagan, Mars after Viking, The Planets: A classic lecture series by Carl Sagan, PhysicsWorld Database @ youtube

- [11] “Chronology of Mars Exploration”. history.nasa.gov.

- [12] Reasenberg, R. D.; Shapiro, I. I.; MacNeil, P. E.; Goldstein, R. B.; Breidenthal, J. C.; Brenkle, J. P.; et al. (December 1979). “Viking relativity experiment – Verification of signal retardation by solar gravity”. Astrophysical Journal Letters. 234: L219–L221.

- [13] Mutch, T.A.; et al. (August 1976). “The Surface of Mars: The View from the Viking 1 Lander”. Science. New Series. 193 (4255): 791–801.

- [14] Timeline of space probes, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #06 | Whewell's Ghost