Thomas Hunt Morgan (1866-1945)

On September 25, 1866, American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, embryologist, and science author Thomas Hunt Morgan was born. He is famous for his experimental research with the fruit fly by which he established the chromosome theory of heredity. Thomas Hunt Morgan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role that the chromosome plays in heredity.

“Except for the rare cases of plastid inheritance, the inheritance of all known cooacters can be sufficiently accounted for by the presence of genes in the chromosomes. In a word the cytoplasm may be ignored genetically.”— Thomas Hunt Morgan, ‘Genetics and the Physiology of Development’, The American Naturalist (1926), 60, 491

Thomas Hunt Morgan – Early Years

Thomas Hunt Morgan was born in Lexington, Kentucky. He joined the State College of Kentucky, today known as the University of Kentucky. Morgan mostly studied natural science and worked with the U.S. Geological Survey during the summer. Morgen started his graduate studies at the recently founded Johns Hopkins University. Under William Keith Brooks, Morgan was able to complete his thesis on the embryology of sea spiders he collected at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. In 1890, Morgan was awarded his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins and was also awarded the Bruce Fellowship in Research. He used his scholarship to travel to Jamaica, the Bahamas and Europe where he conducted further research.

Morphological Research

Also in 1890, Thomas Morgan was appointed associate professor at Johns Hopkins’ sister school Bryn Mawr College. There he taught all morphology-related courses and studied sea acorns, ascidian worms and frogs. Through the years, Morgan got enthusiastic for experimental biology, influenced by the German biologist Hans Driesch in Naples. Back then, there was a considerable scientific debate over the question of how an embryo developed. Basically, the two sides evolved around Wilhelm Roux who believed that hereditary material was divided among embryonic cells, which were predestined to form particular parts of a mature organism, and Hans Driesch who (among his followers) thought that development was due to epigenetic factors, where interactions between the protoplasm and the nucleus of the egg and the environment could affect development. Morgan collaborated with Driesch and they demonstrated that blastomeres isolated from sea urchin and ctenophore eggs could develop into complete larvae, contrary to the predictions of Roux’s supporters. Further, Thomas Morgan was able to show that sea urchin eggs could be induced to divide without fertilization by adding magnesium chloride.

Regeneration

Thomas Morgan returned to Bryn Mawr in 1895 and was appointed full professor upon his arrival. His first book ‘The Development of the Frog’s Egg’ was published two years later. He further started a series of studies on different organisms’ ability to regenerate, which he published in 1901 with the title ‘Regeneration‘.

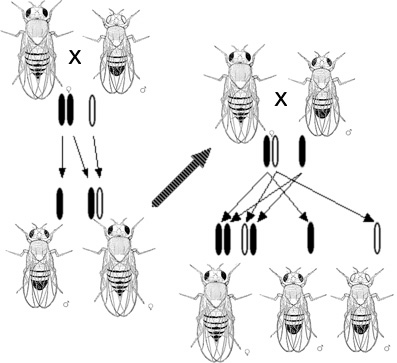

In a typical Drosophila genetics experiment, male and female flies with known phenotypes are put in a jar to mate; females must be virgins. Eggs are laid in porridge which the larva feed on; when the life cycle is complete, the progeny are scored for inheritance of the trait of interest., image: cudmore, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Evolutionary Theories

Morgan joined Columbia University in 1904 in order to focus fully on his experimental work. His research shifted more and more towards the mechanisms of heredity and evolution. Like many biologists back then, he did see evidence for biological evolution but rejected Darwin’s proposed mechanism of natural selection acting on small, constantly produced variations. However, while Morgan was skeptical of natural selection for many years, his theories of heredity and variation were radically transformed through his conversion to Mendelism. Around 1900, Carl Correns,[6] Erich von Tschermak and Hugo De Vries rediscovered Gregor Mendel‘s work and with it the foundation of genetics.[4] As Morgan had dismissed both evolutionary theories, he was seeking to prove De Vries’ mutation theory with his experimental heredity work.

Working with the Fruit Fly

Just like C. W. Woodworth and William E. Castle, Thomas Morgan started to work on the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster around 1908. Together with Fernandus Payne, he mutated Drosophila through physical, chemical, and radiational means and started cross-breeding experiments to find heritable mutations. After no significant finding during their two years of work, a series of heritable mutants appeared, some of which displayed Mendelian inheritance patterns. For instance, Morgan noticed a white-eyed mutant male among the red-eyed wild types. When white-eyed flies were bred with a red-eyed female, their progeny were all red-eyed. A second generation cross produced white-eyed males — a sex-linked recessive trait, the gene for which Morgan named white. He also found a pink-eyed mutant that showed a different pattern of inheritance. In 1911, Morgan published a paper concluding that some traits were sex-linked, the trait was probably carried on one of the sex chromosomes, and other genes were probably carried on specific chromosomes as well.

Genetic Linkage

Morgan and his students whom he had motivated to study flies as well counted the mutant characteristics of thousands of fruit flies and studied their inheritance. The observation of a miniature-wing mutant, which was also on the sex chromosome but sometimes sorted independently to the white-eye mutation, led Morgan to the idea of genetic linkage and to hypothesize the phenomenon of crossing over. Morgan proposed that the amount of crossing over between linked genes differs and that crossover frequency might indicate the distance separating genes on the chromosome.

Mendelian Chromosome Theory

During the following years more and more biologists accepted the Mendelian chromosome theory, which was independently proposed by Walter Sutton and Theodor Boveri, and elaborated and expanded by Morgan and his students. However, the details of the increasingly complex theory, as well as the concept of the gene and its physical nature, were still controversial. Still, due to Thomas Morgan’s success on fruit flies, numerous labs across the globe took up fruit fly genetics and Columbia became the center of an informal exchange network, through which promising mutant Drosophila strains were transferred from lab to lab. Drosophila became one of the first, and for some time the most widely used, model organisms.

Inheritance of eye color in fruit flies according to Morgan

Later Years

During his later career, Morgan returned to embryology and worked to encourage the spread of genetics research to other organisms and the spread of the mechanistic experimental approach to all biological fields. He also became a critic of the growing eugenics movement, which adopted the ideas of genetics in support of racism. Thomas Morgan’s fly-room at Columbia became famous, and he found it easy to attract funding and visiting academics. In 1927 after 25 years at Columbia, and nearing the age of retirement, he received an offer from George Ellery Hale to establish a school of biology in California.[5] In 1919 he was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society, which awarded him the Darwin Medal in 1924 and the Copley Medal in 1939. From 1927 to 1931 he was president of the National Academy of Sciences, of which he had been a member since 1909. In 1928 Morgan was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In the same year he was elected a foreign member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences. In 1933 he received the Nobel Prize for Medicine. In 1935 he was accepted as a corresponding member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. From 1923 he was Corresponding Member and from 1932 Honorary Member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences.

Thomas Hunt Morgan had throughout his life suffered with a chronic duodenal ulcer. In 1945, at age 79, he experienced a severe heart attack and died from a ruptured artery.

Thomas Hunt Morgan and fruit flies, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Thomas Hunt Morgan at nature

- [2] Thomas Hunt Morgan at the Nobel Prize Foundation Webpage

- [3] Thomas Hunt Morgan at Britannica Online

- [4] Gregor Mendel and the Rules of Inheritance, SciHi blog

- [5] George Ellery Hale – Large Telescopes and the Spectroheliograph, SciHi Blog

- [6] Carl Correns and the Principles of Heredity, SciHi Blog

- [7] Thomas Hunt Morgan via Wikidata

- [8] Thomas Hunt Morgan and fruit flies, 2016, Khan Academy @ youtube

- [9] Kenney, D. E.; Borisy, G. G. (2009). “Thomas Hunt Morgan at the Marine Biological Laboratory: Naturalist and Experimentalist”. Genetics. 181 (3): 841–846.

- [10] Morgan, Thomas Hunt; Alfred H. Sturtevant, H. J. Muller and C. B. Bridges (1915). The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity. New York: Henry Holt.

- [11] Timeline for Thomas Hunt Morgan, via Wikidata

Morgan was also in 1928, a Life Member of the Marine Biological Laboratory, a fraternal organization of scientists across the country. (It was located in Woods Hole, MA) along with George Papanicolaou, MD, PhD, who was a regular member of the MBL. Morgan quoted Papanicolaou’s PhD thesis in his 1913 “Heredity and Sex” book. pages 183-85. Morgan was responsible for opening the doors for Dr. Pap to get his first job at Cornell Medical College/NY Hospital in 1914. So in a sense, Morgan was a catalyst to the Pap Test for cervical cancer that Papanicolaou is know for. He (Pap) was born on May 13, 1883, a Friday. So much for being a unlucky day.