Hans Sloane (1660-1753)

On January 11, 1753, Irish born British physician, naturalist and collector Sir Hans Sloane passed away. Sloane is foremost known for bequeathing his collection to the nation, thus providing the foundation of the British Museum.

“The knowledge of Natural-History, being Observation of Matters of Fact, is more certain than most others, and in my slender Opinion, less subject to Mistakes than Reasonings, Hypotheses, and Deductions are;. . . These are things we are sure of, so far as our Senses are not fallible; and which, in probability, have been ever since the Creation, and will remain to the End of the World, in the same Condition we now find them.”

– Hans Sloane

Hans Sloane – Early Years

Hans Sloane was born on 16 April 1660 at Killyleagh in County Down, in the colonial Protestant Plantation of Ulster in the North of Ireland, as the seventh son of Alexander Sloane, agent for James Hamilton, second Viscount Claneboye and later first Earl of Clanbrassil. Actually, he was born the same year that the Royal Society was founded to bring together scientists for weekly meetings where they could witness experiments and discuss scientific topics.[1] His father died when he was six years old. Already as a youth, Sloane collected objects of natural history and other curiosities. This led him to the study of medicine, which he went to London, where he studied botany, materia medica, surgery and pharmacy. His collecting habits made him useful to celebrated botanist John Ray [3] and ‘The Father of Chemistry’, Robert Boyle.[4]

Travels to France

After four years in London he travelled through France, spending some time at Paris and Montpellier, and stayed long enough at the University of Orange-Nassau to take his MD degree there in 1683. In France he met and befriended some of the great botanists and physicians of his time: Joseph Pitton de Tournefort and Pierre Magnol.[1] He returned to London with a considerable collection of plants and other curiosities, of which the former were sent to John Ray and utilized by him for his History of Plants (1686).

Travels to Jamaica

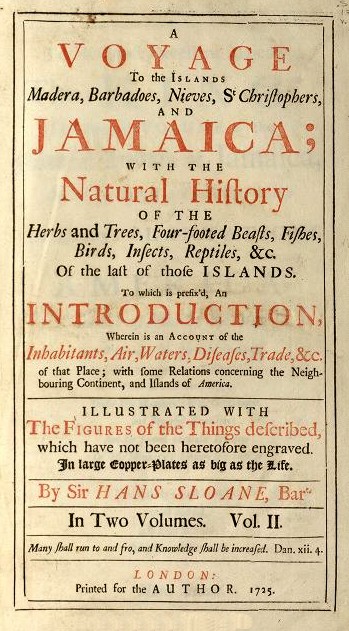

Sloane was elected to the Royal Society in 1685. At the same time attracted the notice of Thomas Sydenham,[5] who gave him valuable introductions to practice. In 1687, he became a fellow of the College of Physicians, and the same year went to Jamaica aboard HMS Assistance as physician in the suite of the new Governor of Jamaica, the second Duke of Albemarle. After the death of Ablemarle, Sloane returned to England in 1689. He then began to work on the information he had gathered in Jamaica and in 1696 published a list of the plants he had collected, the Catalogus Plantarum Quae in Insula Jamaica (often referred to as the Catalogue). In 1693, he became secretary to the Royal Society and edited the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society for twenty years.

Title page, Hans Sloane, Voyage to Jamaica, 1725.

While in Jamaica, Sloane was introduced to cocoa as a drink favored by the local people. He found it ‘nauseous’ but by mixing it with milk made it more palatable. He brought this chocolate recipe back to England where it was manufactured and at first sold by apothecaries as a medicine.[1] Sloane’s recipe later formed the basis for a milk chocolate product manufactured by Cadbury Brothers.[9]

Royal Physician

His practice as a physician among the upper classes was large, fashionable and lucrative. He served three successive sovereigns, Queen Anne, George I and George II. In 1716, Sloane was created a baronet, making him the first medical practitioner to receive a hereditary title. In 1719 he became president of the Royal College of Physicians, holding the office for sixteen years. In 1722, he was appointed physician-general to the army, and in 1727 first physician to George II. In 1727 he succeeded Sir Isaac Newton as president of the Royal Society; he retired from it at the age of eighty.[6]

The Great Collector and his Legacy

However, Sloane’s fame is based on his judicious investments rather than what he contributed to the subject of natural science or even of his own profession. His purchase of the manor of Chelsea, London in 1712, provided the grounds for the Chelsea Physic Garden. His great stroke as a collector was to acquire in 1701 the cabinet of William Courten, who had made collecting the business of his life. He also received objects from friends and patients. When Sloane retired in 1741, his library and cabinet of curiosities, which he took with him from Bloomsbury to his house in Chelsea, had grown to be of unique value. On his death on 11 January 1753 he bequeathed his books, manuscripts, prints, drawings, flora, fauna, medals, coins, seals, cameos and other curiosities – overall more than 71,000 pieces – to the nation, on condition that parliament should pay his executors £20,000, far less than the value of the collection. The bequest was accepted on those terms by an act passed the same year, and the collection, together with George II’s royal library, etc., was opened to the public at Bloomsbury as the British Museum in 1759. A significant proportion of this collection was later to become the foundation for the Natural History Museum.

James Delbourgo, Slavery, Empire, and the Cabinet of Curiosities: Hans Sloane and the Origins of the British Museum, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] About Hans Sloane, Natural History Museum, London

- [2] The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, SciHi Blog, November 23, 2013.

- [3] John Ray and the Classification of Plants, SciHi Blog

- [4] Robert Boyle – The Sceptical Chemist, SciHi Blog

- [5] Thomas Sydenham – the English Hipocrates, SciHi Blog

- [6] Standing on the Shoulders of Giants – Sir Isaac Newton, SciHi Blog

- [7] Sir Hans Sloane: Voyage to Jamaica, 1725, via Botanicus

- [8] Sir Hans Sloane, at The British Museum

- [9] Sir Hans Sloane, Baronet, British physician, at Britannica Online

- [10] Works by or about Hans Sloane at Wikisource

- [11] Sir Hans Sloane at Wikidata

- [12] James Delbourgo, Slavery, Empire, and the Cabinet of Curiosities: Hans Sloane and the Origins of the British Museum, 2018, UVA Medical Center Hour @ youtube

- [13] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Sloane, Sir Hans“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 243.

- [14] “Voyage to the Islands: Hans Sloane, Slavery and Scientific Travel in the Caribbean”, John Carter Brown Library online exhibition

- [15] Timeline for Sir Hans Sloane, via Wikidata