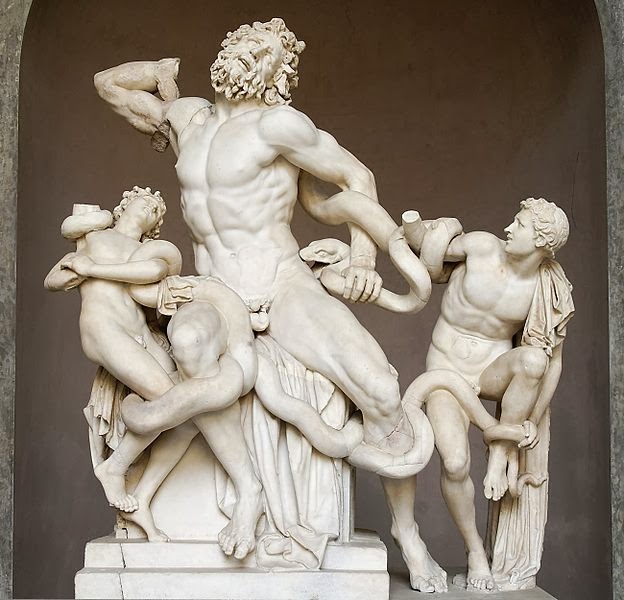

Laocoön and His Sons in the Vatican Museum

On January 14, 1506, Felice de Fredis rediscovered the statue of Laocoön and his Sons in his vineyards close to the ruins of Emperor Nero‘s Golden House palace on the Esquiline Hill in Rome. The discovery of the Laocoön made a great impression on Italian artists and continued to influence Italian art into the Baroque period.

The Myth of Laocoön and the Greek Sculpture

Laocoön was a Trojan priest of Poseidon. The story of his death goes in two different directions. Some say, he was killed along with both of his sons after attempting to expose the fraud if the Trojan Horse by striking it with a spear. Another legend states that he was killed for having sex with his wife in the temple of Poseidon, wherefore the God of the Sea sent the venomous snakes to the man and his family. Since this work is very similar to the figure of Alcyoneus, which is part is the Pergamon Altar, the work ‘Laocoön and his Sons‘ is agreed to be that of the Hellenistic Pergamone baroque, which arose around 200 BC. Already the Roman author Pliny the Elder mentioned that

“Laocoön, for example, in the palace of the Emperor Titus, [is] a work that may be looked upon as preferable to any other production of the art of painting or of [bronze] statuary. It is sculptured from a single block, both the main figure as well as the children, and the serpents with their marvellous folds. This group was made in concert by three most eminent artists, Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, natives of Rhodes“.[5]

The original sculpture of the sculptors Hagesandros, Polydoros and Athanadoros from Rhodes is only preserved in a 1.84 metre high marble copy from the second half of the 1st century BC or the beginning of the 1st century AD. The original was probably a bronze sculpture from Pergamon from around 200 BC, which has not been preserved.

The Rediscovery

In 1506, Laocoön and his Sons were unearthed in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis. In March 1506, the Laocoon Group was handed over to Pope Julius II, who took it over into his personal possessions. The finder was rewarded with the customs revenue of the Porta San Giovanni in Rome, a further reward of 1500 ducats under the next Pope Leo X and a final resting place in the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli on the Capitol. Michelangelo was called along with the Florentine architect Guiliano da Sangallo and his son [6]. At its discovery, the statue lacked of Laocoön’s right arm, parts of the hand of one child, the right arm of the other, as well as various sections of snake. Also, the older son, on the right, was detached from the other two figures. In August of the same year, the group was placed for public viewing in a niche in the wall of the brand new Belvedere Garden at the Vatican. Since then the group has been in the Vatican Museums in Rome, with a brief interruption between 1798 and 1815, when they were in Paris as spoils of war after the Treaty of Tolentino was signed.

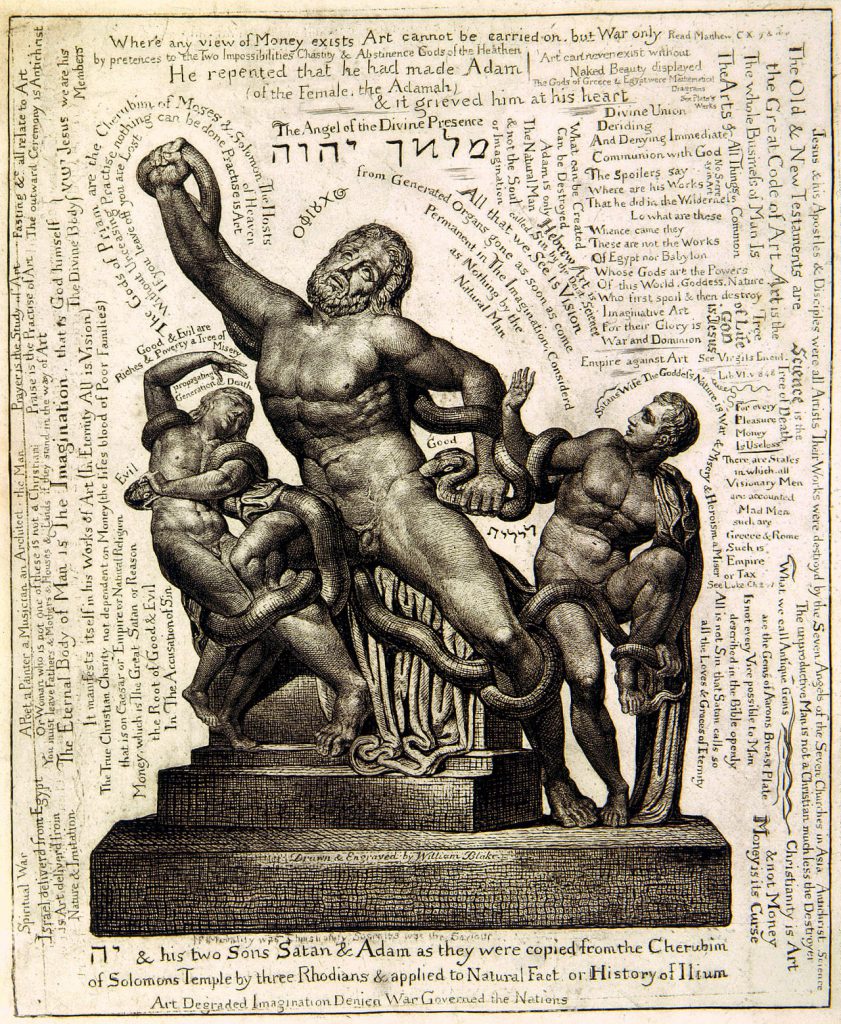

William Blake, Laocoön print, c. 1820

First “Updates”

Throughout the years, the masterpiece was restored several times. Giovanni Antonio Montorsoli, a pupil of Michelangelo, added his version of Laocoön’s outstretched arm in 1532, which remained in place until modern times. A section to the younger son’s arm was added in the 1720s and after the group returned from Paris, the statue was ‘tidied up’ by Antonio Canova. In 1905, the right arm of Laocoon was found by Ludwig Pollak, an archaeologist and art dealer, and the arm, which had previously been stretched, was replaced in 1960 by the original arm angled at the elbow. In the process, additions to the sons’ arms (the right arm of the son to his right and the right hand of the son to his left) were removed.

Influence on Baroque Art

The discovery of the Laocoön continued to influence Italian art into the Baroque period and gave great insights on Italian artists in history. It is widely assumed, that Michelangelo was highly influenced by the masterpiece, especially in concerns of the depiction of the male figures, such as Dying Slave or Bondaged Slave, created for Julius II‘s tomb. The Sistine Chapel can also be associated with the physical composition of the Laocoon group in the body depiction of the ceiling paintings. The sculpture and Pliny’s statement that the Laocoön is “a work to be preferred to all that the arts of painting and sculpture have produced” started whole new debates considering the limits of art and ideals of art. Virgil’s verse was compared with the sculpture in an essay by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, and he argued that the artists could not realistically depict the physical suffering of the victims, as this would be too painful. Johann Joachim Winkelmann however wrote about the paradox of admiring beauty while seeing a scene of death and failure.[7]

Joe Becherer, Laocoön: Time and Space – Insights from the Director, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] An Ancient Masterpiece Or a Master’s Forgery? New York Times, April 18, 2005

- [2] Laocoon and the expression of pain

- [3] Digital Sculpture Project: Laocoön

- [4] Outscreaming the Laocoön: Sensation, Special Affects, and the Moving Image

- [5] Pliny the Elder and the Destruction of Pompeii, SciHi Blog, August 14, 2014.

- [6] Michelangelo Buonarotti – the Renaissance Artist, SciHi Blog, March 6, 2017.

- [7] The Prophet of Modern Archeology – Joachim Winckelmann, SciHi Blog, December 9, 2013.

- [8] Laocoön by William Blake, at Wikisource

- [9] Laocoon and his Sons at Wikidata

- [10] Joe Becherer, Laocoön: Time and Space – Insights from the Director, Snite Museum of Art @ youtube

- [11] “Volpe and Parisi”: Digital Sculpture Project: Laocoon. “Laocoon: The Last Enigma”, translation by Bernard Frischer of Volpe, Rita and Parisi, Antonella, “Laocoonte. L’ultimo engima,” in Archeo 299, January 2010, pp. 26–39

- [12] Timeline with Hellenistic sculptures from Wikidata