John Martin’s “Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum” (1821)

On August 25, 79 AD, Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher Pliny the Elder died, while attempting the rescue by ship of a friend and his family from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius that had just destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Unfortunately, there don’t exist contemporary pictures or portraits of Pliny the Elder. Thus, I decided to show you an also imaginary picture of the destruction of Pompeii instead.

“Fortes Fortuna iuvat.”

(Fortune favours the brave.)

– attributed by Pliny the Younger to his uncle during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in which the Elder died

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Cecilius Secundus, known as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman scholar, encyclopedist, and nationalist who was born in 23 AD, in Novum Comum in Gallia Cisalpine (today Como, Italy). He completed his studies in Rome where he received education in literature, oratory, and law, as well as military training. In 46 AD at the age of 23, he began a military career by serving in Germany under Pomponius Secundus, rising the rank of cavalry commander.[1] Twelve years later, he returned to Rome. Legal advocate during the reign of emperor Nero (died in 68) he gained favor under Vespasian and assumed various official positions: he served as a procurator in Gaul, Africa and Spain, where he gained a reputation for integrity. He also served on the imperial council for both Vespasian and Titus.

Despite his active public life, Pliny the Elder still found time to write enormous amounts of material. He was the author of at least 75 books, not to mention another 160 volumes of unpublished notebooks. His books included volumes on cavalry tactics, biography, a history of Rome, a study of the Roman campaigns in Germany (twenty books), grammar, rhetoric, contemporary history (thirty-one books), and his most famous work, his one surviving book, Historia Naturalis (Natural History), published in A.D. 77. Natural History consists of thirty-seven books including all that the Romans knew about the natural world in the fields of cosmology, astronomy, geography, zoology, botany, mineralogy, medicine, metallurgy, and agriculture.[1]

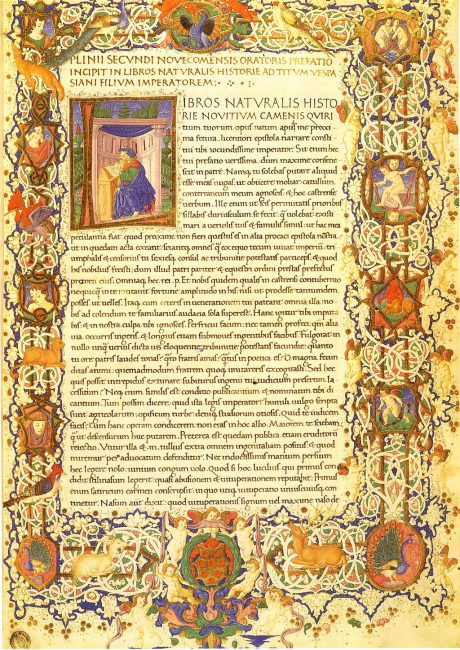

Pliny the Elder, Natural History in ms. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 82.4, fol. 3r.

Naturalis Historia

Published during the last two years of Pliny‘s life, the Naturalis Historia is one of the largest works surviving from classical times. And, although it contains many mistakes, some due no doubt to the author’s untimely death, which prevented any revisions, there is a surprising level of accuracy. He states correctly, for example, that Venus is the only heavenly body, other than the Sun and Moon, that casts a visible shadow; or that a bird egg can be made flexible by placing it in vinegar and dissolving away its hard outer shell. Pliny’s writings offer not only insights into nature itself, but also into the Roman conception of nature, which differed substantially from our own.[2] In Naturalis historia, Pliny arranged traditional scientific knowledge of Greek authors such as Aristotle, Theophrastus and Hippocrates of Kos directly from manuscripts and related it to new geographical knowledge of Cato, Varros, Mucianus and others. The work is especially characterized by its structure: It consists of 37 volumes that can be used independently of each other. One volume of the Naturalis historia could thus serve as a handbook for one subject area. The encyclopedia covered cosmography (Book 2), geography (Books 3-6), anthropology (Book 7), zoology (Books 8-11), botany (Books 12-19), medicine (20-32), metallurgy and mineralogy as well as painting and art history (Books 33-37). Book 9 on zoology deals with the purple dyeing of this period.

Pliny (left) presents Emperor Titus with a volume of writing with the dedication of his work. Book illumination in a manuscript of the Naturalis historia. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 82.1, fol. 2v (early 13th century)

Pliny’s Death

Pliny the Elder did not marry and had no children. In his will he adopted his nephew, Pliny the Younger (Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus Minor), which entitled the latter to inherit the entire estate. An account of Pliny’s death is given in a letter from his nephew to the historian Tacitus:

He [Pliny the Elder] was at that time with the fleet under his command at Misenum. On August 24th [79 AD], about one in the afternoon, my mother asked him to look at a cloud of the most peculiar size and shape. He had been sunbathing earlier, which he had followed with a cold bath and a light lunch. He had then returned to his books. But he rose at once and went to high ground where he could get a better view of this remarkable phenomenon.[…] To a man of such learning as my uncle, this phenomenon seemed extraordinary and well worth investigation. He ordered a light ship prepared, and told me I could come along if I liked.[…]They tried to decide whether it would be wiser to remain inside their houses — which now were being shaken to their foundations with repeated, violent concussions from the eruption — or to flee to the open fields, where the stones and cinders rained down in such heavy showers that, although they were individually light, they seemed to threaten annihilation. […] They decided to go down to the shore to see whether they could escape by sea, but the waves were still running too high. There my uncle lay down on a sail that had been spread for him, and called twice for some cold water, which he drank. Then a rush of flame, with the reek of sulfur, made everyone scatter, and made him get up. He stood with the help of his servants, but at once fell down dead, suffocated, as I suppose, by some potent, noxious vapor. He had always had a weak respiratory tract, which was often inflamed and obstructed.[3]

The cause of death is now considered unclear. Researchers are discussing death by suffocation, poisoning, asthma attack, heart attack or stroke as possible causes.

Pliny the Elder and Nero – Professor Matthew Leigh, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Pliny the Elder at Wolfram ScienceWorld

- [2] Pliny the Elder at macroevolution.net

- [3] The Letter of Pliny the Younger to Tacitus, describing the Death of his uncle Pliny the Elder

- [4] Pompeii – Conquered, Burried, and Rediscovered, SciHi Blog

- [5] Pliny the Elder at Wikidata

- [6] Melvyn Bragg (8 Jul 2010). “Pliny the Elder”. In Our Time (Podcast). BBC Radio 4.

- [7] Works by or about Pliny the Elder at Internet Archive

- [8] Works written by or about Pliny the Elder at Wikisource

- [9] Pliny the Elder and Nero – Professor Matthew Leigh, Roman Society @ youtube

- [10] Pliny the Elder (1855). “The Natural History“. John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley (translators and editors); Gregory R. Crane (Chief editor). Taylor and Francis; Tufts University: Perseus Digital Library.

- [11] Timeline of renown People who died in a Volcano eruption, via Wikidata and DBpedia