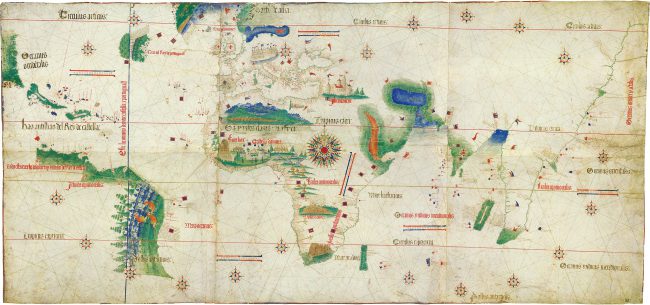

Cantino planisphere 1502, one of the earliest surviving charts showing the explorations of Pedro Álvares Cabral to Brazil. The Tordesillas line is also depicted.

On May 4, 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued the papal bull ‘Inter caetera‘ (Among other [works]), which granted to the Catholic Majesties of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain all lands to the “west and south” of a pole-to-pole line 100 leagues west and south of any of the islands of the Azores or the Cape Verde islands. It established a dividing line between the Castilian and Portuguese spheres of power.

No Agreement between Portugal and Spain

In the late 15th century, Spain and Portugal had a quite difficult relationship due to their competing explorers and the wish to own as many colonial territories as possible along the African coast line. The previous years, several papal bulls were issued and the Spanish government came to realize the authority of these bulls. They initiated diplomatic discussions over the rights to possess and govern the newly found lands. Even though the Spanish and Portuguese delegates debated and negotiated for several months concerning this topic, they could not find any agreement. Before Christopher Columbus received support for his voyage from Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain, he had first approached King John II of Portugal. The king’s scholars and navigators reviewed Columbus’s documentation, determined that his calculations grossly underestimated the diameter of the Earth and thus the length of the voyage, and recommended against subsidizing the expedition. Upon Columbus’s return from his first voyage to the Americas, his first landing was made in the Portuguese Azores; a subsequent storm drove his ship to Lisbon on 4 March 1493. Hearing of Columbus’s discoveries, the Portuguese king informed him that he believed the voyage to be in violation of the 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas. The treaty had been ratified with the 1481 papal bull Aeterni regis, which confirmed previous bulls of 1452 (Dum diversas), 1455 (Romanus Pontifex), and 1456 (Inter caetera), recognizing Portuguese territorial claims along the West African coast.

Inter Cetera

Spain then contacted Pope Alexander VI, who was known to be befriended with the Spanish King. They urged the pope to issue a new bull favorable to Spain. Alexander VI did so and issued four edicts in May 1493. The third superseded the first two, and the fourth, titled Inter caetera, superseded the third. A fifth edict, Dudum siquidem of 26 September 1493, supplemented the Inter caetera. Compared to the Treaty of Alcáçovas of 1479, the new demarcation line meant a significant expansion of Castilian power. In the Treaty of Alcáçovas, the areas south of the Canary Islands had been assigned to the Portuguese in particular, including future discoveries and without any limitation to the west. As a result, the Portuguese King John II disagreed with the new demarcation line. The Portuguese tried to achieve an improvement by trading directly with the Castilians, which led to the Treaty of Tordesillas and together they defined and delineated a zone of Spanish rights exclusive of Portugal. However, the agreement was illegal in relation to other states, even though Spain spent much time and effort to persuade further European leaders on the validity.

The meridian to the right was defined by Inter caetera, the one to the left by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Modern boundaries and cities are shown for purposes of illustration.

“West and South”

The phrase “west and south” with reference to the location of the dividing line itself is puzzling. A normal meridian cannot be meant by literal understanding, since such a line reaches to the North Pole and cannot lie “south” of a group of islands. In addition, a meridian extends to the South Pole, so that countries or islands cannot lie “south” of the whole meridian. Instead, the section of the meridian that lies south of the two archipelagos could be meant; in other words, areas north of the Azores should be excluded from the demarcation. For example, British geographers John Dee and Richard Hakluyt in the Elizabethan era interpreted the phrase “west and south” in this sense and used the bull Inter caetera as an argument for rejecting Spanish claims in North America.

The Treaty of Tordesillas

The treaty moved the line further west to a meridian 370 leagues west of the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands, now explicitly giving Portugal all newly discovered lands east of the line. The treaty also allowed the two countries to pass each other toward the west or east, and still possess whatever lands they were first to discover. An important effect of the combination of this papal bull and the Treaty of Tordesillas was that nearly all the Pacific Ocean and the west coast of North America were given to Spain. In response to Portugal’s discovery of the Spice Islands in 1512, the Spanish put forward the idea, in 1518, that Pope Alexander VI had divided the world into two halves. Further European states now claimed that the Pope had not the right to convey sovereignty of regions as vast as the New World.

The Consequences

In response to Portugal’s discovery of the Spice Islands in 1512, the Spanish put forward the idea, in 1518, that Pope Alexander had divided the world into two halves. By this time, however, other European powers had overwhelmingly rejected the notion that the Pope had the right to convey sovereignty of regions as vast as the New World. On this day, numerous groups, representing indigenous people of the Americas have organized protests and raised petitions seeking the repeal of the papal bull Inter caetera. They claim, the bull led to the subjugation of their folks, and they want to remind Catholic leaders of the record of conquest, disease and slavery in the Americas.

Emily O’Brien, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Reflections on the Renaissance Papacy, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] English Translation of Inter Caetera

- [2] Inter Cetera in Latin at Wikisource

- [3] What you don’t know about Pope Alexander VI

- [4] Papal Bull Website

- [5] Pedro Álvares Cabral and the Discovery of Brazil, SciHi Blog

- [6] Vasco da Gama and the Route to India, SciHi Blog

- [7] The Treaty of Tordesillas at Wikidata

- [8] Emily O’Brien, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Reflections on the Renaissance Papacy, SFU History @ youtube

- [9] Waisberg, Tatiana, “The Treaty of Tordesillas and the (Re)Invention of International Law in the Age of Discovery“ Journal of Global Studies, No 47, 2017.

- [10] Translation of the Treaty of Tordesillas by Davenport.

- [11] Edward G. Bourne, ‘The History and Determination of the Line of Demarcation by Pope Alexander VI, between the Spanish and Portuguese Fields of Discovery and Colonization’, American Historical Association, Annual Report for 1891, Washington, 1892; Senate Miscellaneous Documents, Washington, Vol.5, 1891–92, pp. 103–30.

- [12] Timeline of historical political rivalries before the First World War, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #38 | Whewell's Ghost