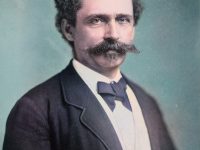

Mackay, Edgeworth David, and Mawson at the Southern Magnetic Pole, 17 January 1909

On January 16, 1907, Australian geologists Tannatt William Edgeworth David and Douglas Mawson together with Scottish physician Alistair Mackay, being part of the British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09, otherwise known as the Nimrod Expedition, led by Ernest Shackleton, reached the magnetic southpole. The major goal of the famous Nimrod Expedition was to be the first to reach the South Pole. Even though this goal was not fulfilled completely, the expedition’s southern march reached a Farthest South latitude of 88° 23′ S, just 180.6 km from the pole.

Shackleton’s Pride and the Nimrod Expedition

Ernest Shackleton [5] was already appointed junior officer on Robert Falcon Scott’s first Antarctic expedition but was sent home early due to a physical collapse.[6] Apparently, the references to Shackleton’s physical breakdown made in Scott’s The Voyage of the Discovery, published in 1905, reopened the wounds to Shackleton’s pride. Shackleton set himself the personal goal to return to the Antarctic and outperform Scott. In 1907, he received his first financial backing and acquired the Nimrod, which was inspected by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.

Base Camp

On 11 August 1907 Nimrod and its crew sailed south with Shackleton following them with a faster ship. In New Zealand the whole crew met, departing to Antarctica on New Year’s Day, 1908. The first Icebergs were sighted in mid January and the Barrier was sighted on 23 January. Two days later the party headed for McMurdo Sound. On 3 February Shackleton decided not to wait for the ice to shift but to make his headquarters at the nearest practicable landing place, Cape Royds. The ship was moored, and a suitable site for the expedition’s prefabricated hut was selected. In the following days the expedition was busy with the landing of stores and equipment during bad weathers. The expedition’s hut, a prefabricated structure measuring 10m x 5.8 m, was ready for occupation by the end of February. It was divided into a series of mainly two-person cubicles, with a kitchen area, a darkroom, storage and laboratory space.

Farther South

During the winter 1908 the expedition printed around 30 copies of the expedition’s book, Aurora Australis and prepared for the following season’s major journeys, which were to include attempts on both the South Pole and the South Magnetic Pole. Shackleton’s choice of a four-man team for the southern journey to the South Pole was largely determined by the number of surviving ponies. The march began on 29 October 1908. Shackleton had calculated the return distance to the Pole as 2,767 km and his initial plan allowed 91 days for the return journey. Between 9 and 21 November they made good progress, but the ponies suffered on the difficult Barrier surface, and the first of the four had to be shot when the party reached 81°S. On 26 November a new farthest south record was established as they passed the 82° 17′ mark set by Scott’s southern march in December 1902. Shackleton’s party covered the distance in 29 days compared with Scott’s 59, using a track considerably east of Scott’s to avoid the surface problems the earlier journey had encountered. While moving even further through unknown territory, the Barrier surface became increasingly difficult and two further ponies died. While traveling on the Beardmore glacier the last remaining pony disappeared down a deep crevasse.

Only 100 miles to the South Pole

Shortly after Christmas, the crew completed the glacier ascent, knowing that their food supplies would not be enough to reach the Pole and come back to the hut. On 4 January 1909 Shackleton finally accepted that the Pole was beyond them, and revised his goal to the symbolic achievement of getting within 100 geographical miles of the Pole. On January 9 1909, the march ended, the British flag was planted and the polar plateau was named after King Edward VII.

The Way Back

Shackleton landed back in in New Zealand on 23 March 1909 and in June, he was met at London’s Charing Cross Station by a very large crowd, which included RGS president Leonard Darwin and a rather reluctant Captain Scott. Shackleton was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order by King Edward, who later conferred a knighthood on him. The farthest south record of the Nimrod Expedition stood for less than three years, until Amundsen reached the South Pole on 15 December 1911. Roald Amundsen also paid tribute to Shackleton’s achievements in retrospect, having been the first to reach the geographical South Pole.[7]

The Heart of the Antarctic

Shackleton’s expedition report entitled The Heart of the Antarctic was first published in November 1909 as a two-volume work by the London publisher William Heinemann. The first volume contained Shackleton’s descriptions of the preparation and course of the expedition, including the failed march to the geographical South Pole. Edgeworth David‘s treatise on the march to the Antarctic magnetic pole, five chapters on the scientific results of the journey, and a medical bulletin by Eric Marshall are included in the second volume. At the same time as the book was published, an overview article appeared in the Geographical Journal. James Murray also published the results of the biological work in his own work in 1910.

Ernest Shackleton, Polar Explorer – Stephen Scott Fawcett LECTURE, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Nimrod Expedition at Heritage Antartica

- [2] The Nimrod Expedition at the BBC

- [3] The Nimrod Expedition at Glasgow Digital Library

- [4] The Nimrod expedition at Wikidata

- [5] Ernest Shackleton and his South Pole Expeditions, SciHi Blog

- [6] Robert Scott’s Last Expedition, SciHi Blog

- [7] Amundsen’s South Pole Expedition, SciHi blog

- [8] Ernest Shackleton, Polar Explorer – Stephen Scott Fawcett LECTURE, Haslemere Festival 2019, 12/05/2019, Haslemere Festival @ youtube

- [9] Preston, Diana (1997). A First Rate Tragedy: Captain Scott’s Antarctic Expeditions. London: Constable & Co.

- [10] Riffenburgh, Beau (2005). Nimrod: Ernest Shackleton and the Extraordinary Story of the 1907–09 British Antarctic Expedition. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- [11] Crane, David (2005). Scott of the Antarctic. London: Harper Collins.

- [12] Timeline of expeditions from the 19th century to 1920, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #23 | Whewell's Ghost