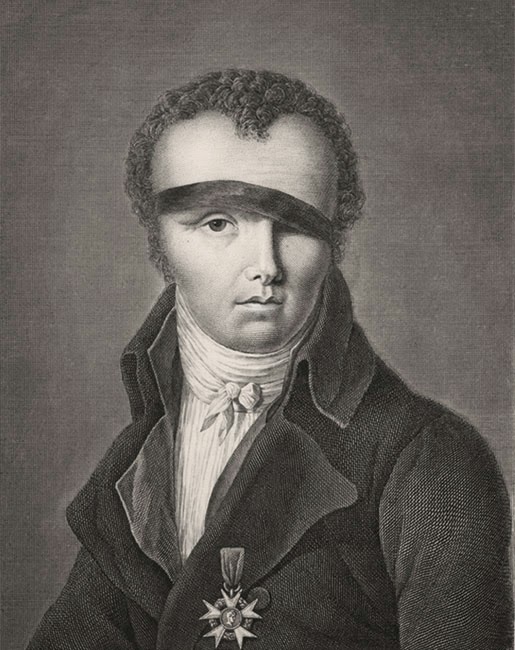

Nicolas-Jacques Conté (1755-1805)

On August 4, 1755, French painter, inventor, army officer and balloonist, Nicolas-Jacques Conté was born. Among others, he is credited with the invention of the modern pencil. Moreover, some consider him one of the greatest inventive minds of the eighteenth century. He distinguished himself for his mechanical genius which was of great avail to the French army in Egypt. Napoleon Bonaparte called him “a universal man with taste, understanding and genius capable of creating the arts of France in the middle of the Arabian Desert.”

Background Nicolas-Jacques Conté

Nicolas-Jacques Conté was born at Saint-Céneri-près-Sées (now Aunou-sur-Orne) in Normandy, France, as one of six children. He was the descendent of a family of farmers who had cultivated the same fields for over two hundred years. Of his family we know little except that one of his brothers took over the responsibilities of the estate after the death of his father, while the other left the household to establish his own farm. Two of his sisters became nuns at the Hotel Dieu de Sées. It is related that, at the age of nine, Conté fashioned a violin with a knife as his sole tool. If the story is true, it records the earliest indication of his later accomplishments. One of his distinctive traits was the ability to imagine, design, and fabricate beyond the normal limitations of the equipment available to him. He was given a job as assistant to the gardener at the Hotel Dieu de Sées, where he was also given the task of aiding a painter who was commissioned to decorate the chapel of the convent with a series of panels. He worked at grinding pigment and cleaning brushes and began to learn about painting by observation. When the painter fell ill, Conté asked if he might try his hand. He argued that he should be allowed to do one panel which, if considered unsuccessful, could be painted over. Needless to say, the trial was acceptable and he completed the decoration of the chapel. The beginning of his career as an artist was assured.[1]

Aeronautics

One of his early interest while still at Sées was in the newly developing science of aeronautics. He made at least one hot air balloon which he flew in the public square. He contributed to the improvement of the production of hydrogen gas, as well as the treatment of the gas bag of the balloon itself. He also took up portrait painting, from which he derived a considerable income. Passionately interested in mechanical arts and science, he began displaying his inventive faculty during the French Revolution. In 1794, as director of the Aerostatic (Montgolfiers) school he taught chemistry, physics and mechanics. He lost the left eye in an explosion experimenting with gases and varnish. Later he invented a telegraphic system for long distance communication in balloons.

Pencils

Prior to Conté’s time pencils had almost all been made from lumps of pure graphite, mined from the Borrowdale mine in England and sawed into strips that were then encased in wood. In 1794 all this changed when Conté, already a famous inventor and scientist was charged by his patron, Carnot, to invent a substitute for the now expensive and difficult to come by pure English graphite. The French Republic was at that time under economic blockade and unable to import graphite from Great Britain, the main source of the material. It took him just 8 days to produce a workable lead. In just over a week he had invented what was to become known as the Conté process: a way to make pencil leads from powdered graphite and clay that us still, essentially, used today. Previous attempts to use graphite in powdered form (perhaps from material extracted from low quality ore in poorer mines, or in an attempt to use the waste products generated by sawing and cutting) had always foundered but Conté worked out how to mix graphite in powdered form with clay, and bake it, in such a way that not only did he produce a usable lead, but was able to make leads in varying degrees of hardness. As well as his process for mixing leads, Conté is also generally credited with inventing the machinery needed to make round leads, and he can truly be said to be the creator of the pencil. Indeed, for about 100 years, pencils in France were known as the crayons Conté and of course pencils continue to be made with the Conté brand name to this day [2]. At the 1798 Exposition des produits de l’industrie française Conté won an honorable distinction, the highest award, for his “crayons of various colours”.

Egyptian Adventure

After improving the barometer he parted with the scientific expedition to Egypt organized by Napoleon Bonaparte. There, Nicolas Jacques started his participation in the conquest of Egypt by inventing a tan method to avoid the fast rusting of metals provoked by the Egyptian weather. He studied the physics of mirages and the arts and production methods of the Egyptian people. During the Cairo’s rebellion most of the instruments of the Arts and Sciences commission were lost. Conté said “We have no instruments; it is simple, we are going to reconstruct them“. He played an important role in developing many different procedures including fabrication of cardboard, coins, powder, windmills, chirurgical instruments, telescopes, cannon carriages for the desert, ovens and many other instruments. Moreover, he also participated in the reproduction of the Rossette stone by chalcography. The reproduction that was the basis for Champollion’s work on Egyptian hieroglyphes. No wonder that Napoleon said about him “Conté was able to recreate the French arts in the middle of Arabian deserts“. In 1801, coming back to France, Conté directed the elaboration of “Description de l’Égypte“, a wonderful work about Egypt.

Back in France

On his return to France, Conté was commissioned by the government to direct the realization of the great work that the newly created Egyptian commission was to publish. The number of monuments and objets d’art that had to be represented was immense. The detail of the engraving alone, using ordinary processes, would have required enormous expenditure and taken many years. Conté imagined an engraving machine by which all the work on the backgrounds, skies and masses of the monuments could be done easily and quickly. The usefulness of this machine was not limited to the work on Egypt: other artists introduced it into their workshops. Furthermore, he invented an engraving machine for the illustrations of the Description. When his wife died in 1804 at the height of his fame, the loss put an end to his inventiveness. “Now I am no longer filled with the desire to please her.” On December 5, 1805, he died from an aneurism at the age of 50.

Milton Friedman – Lesson of the Pencil, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Nicolas-Jacques Contè at Wiliam H. Beck

- [2] Nicolas-Jacques Conté at Pencil Heroes

- [3] Nicolas-Jacques Contè at Groupe N.J.Conté

- [4] Cracking the Code – Jean Francois Champollion and the Rosetta Stone

- [5] Mary Had a Little Lamb – Edison and the Phonograph

- [6] General Thomas Alexandre Dumas – Napoleon’s ‘Black Devil’

- [7] Nicolas-Jacques Conté at Wikidata

- [8] Milton Friedman – Lesson of the Pencil, LibertyPen @ youtube

- [9] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [10] Timeline of Members of the Commission of Sciences and Arts, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #51 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: What Are Conte Crayons? The Conte Format Explained - Artypod