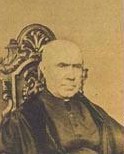

Nicholas Callan’s Induction Coil at the National Science Museum, Maynooth

On December 22, 1799, Irish priest and physicist Nicholas Callan was born. Callan invented the induction coil (1836) before that of better-known Heinrich Ruhmkorff. Callan‘s coil was built using a horseshoe shaped iron bar wound with a secondary coil of thin insulated wire under a separate winding of thick insulated wire as the “primary” coil. Each time a battery‘s current through the “primary” coil was interrupted, a high voltage current was produced in the electrically separate “secondary” coil.

Early Years and First Experiments in Electricity

Nicholas Joseph Callan attended school at an academy in Dundalk, Louth, Ireland. His local parish priest, Father Andrew Levins, then took him in hand as an altar boy and Mass server, and saw him start the priesthood at Navan seminary. He entered Maynooth College where he studied natural and experimental philosophy under Cornelius Denvir who is believed to have introduced the experimental method into his teaching, and had an interest in electricity and magnetism. In 1823, Callan was ordained priest and moved to Rome to study at Sapienza University, obtaining a doctorate in divinity in 1826. In Rome, Nicholas Callan became interested in the works of the pioneers in electricity such as Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta.[4,5] Back in Ireland, in 1826, Callan was appointed Professor of Natural Philosophy at Maynooth. He remained in that post until his death in 1864.

Nicholas Callan (1799-1864)

The Induction Coil

Callan started working with electricity in his basement laboratory at the college. During the 1839s, he was inspired by William Sturgeon and Michael Faraday [6] to work on the idea of the induction coil. An induction coil produces an intermittent high-voltage alternating current from a low-voltage direct current supply. It has a primary coil consisting of a few turns of thick wire wound around an iron core and subjected to a low voltage. Wound on top of this is a secondary coil made up of many turns of thin wire. An iron armature and make-and-break mechanism repeatedly interrupts the current to the primary coil, producing a high-voltage, rapidly alternating current in the secondary circuit.

It is believed that Nicholas Callan invented the induction coil because he needed to generate a higher level of electricity than currently available. He used a bar of soft iron and copper wire wrapped around it. Callan connected the beginning of the first coil to the beginning of the second. Finally, he connected a battery, much smaller than the enormous contrivance just described, to the beginning and end of winding one. He found that when the battery contact was broken, a shock could be felt between the first terminal of the first coil and the second terminal of the second coil.

Further Experiments

Back then, Nicholas Callan conducted further experiments and the tests showed that the coil device could bring the shock from a small battery up the strength level of a big battery. He tried to make a bigger coil and with a battery of only 178 mm plates, the device produced power enough for an electric shock “so strong that a person who took it felt the effects of it for several days“. Apparently, Callan thought of his work as an electromagnet, however, he actually made a primitive induction transformer. Further, Callan’s induction coil used an interrupter that consisted of a rocking wire that repeatedly dipped into a small cup of mercury. Due to its action, which could make and break the current going into the coil, he called his device the “repeater”. However, it is believed that it was the first transformer. In 1837 Callan produced his giant induction machine: using a mechanism from a clock to interrupt the current 20 times a second, it generated 380 mm sparks, an estimated 60,000 volts and the largest artificial bolt of electricity then (probably) seen.

A New Type of Battery

Callan experimented with designing batteries after he found the models available to him at the time to be insufficient for research in electromagnetism. Some previous batteries had used rare metals such as platinum or unresponsive materials like carbon and zinc. Callan found that he could use inexpensive cast-iron instead of platinum or carbon. For his Maynooth battery he used iron casting for the outer casing and placed a zinc plate in a porous pot (a pot that had an inside and outside chamber for holding two different types of acid) in the centre. Using a single fluid cell he disposed of the porous pot and two different fluids. He was able to build a battery with just a single solution. Callan also discovered an early form of galvanisation to protect iron from rusting when he was experimenting on battery design, and he patented the idea.

Legacy

But why did Callan fall into oblivion and why was his invention of the induction coil attributed to a German-born Parisian instrument maker, Heinrich Ruhmkorff? Callan’s place of work, Maynooth, was a theological university where the natural sciences had a stepmotherly existence. In the opinion of Callan’s colleagues, his research was a waste of time. In such an atmosphere, Callan’s pioneering work was simply forgotten after his death. Ruhmkorff, like all instrument makers, simply put his name on every instrument he built. The “Ruhmkorff coil” found its way into the textbooks. It was never questioned until P. J. McLaughlin published his research on Callan’s papers in 1936,[11] which irrefutably proved that the inventor of the induction coil was Nicholas Callan of Maynooth. The first recognition of Callan as an inventor was in the 1953 edition of Gregory and Hadley’s Textbook of Physics, revised by George Lodge, Senior Science Master at St. Columba’s College, Rathfarnham.

Nicholas Callan died in 1864 and is buried in the cemetery in St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth.

Walter Lewin, 8.02x – Lect 16 – Electromagnetic Induction, Faraday’s Law, Lenz Law, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Nicholas Callan at Famous Irish Scientists

- [2] Nicholas Callan at Maynooth University

- [3] Nicholas Callan Biography

- [4] Alessandro Volta and the Electricity, SciHi Blog

- [5] Luigi Galvani’s Discoveries in Bioelectricity, SciHi Blog

- [6] A Life of Discoveries – the great Michael Faraday, SciHi Blog

- [7] Nicholas Callan at Wikidata

- [8] Nicholas Callan (July 1848) “On the construction and power of a new form of Galvanic battery,” Philosophical Magazine, series 3, vol. 33, no. 219, pages 49–53.

- [9] M.T. Casey (December 1985) “Nicholas Callan – priest, professor and scientist,” IEE Proceedings, vol. 132, pt. A, no. 8, pages 491–497

- [10] O’Hara, James G.Callan, Nicholas Joseph (1799–1864), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- [11] McLaughlin, P. J. “Dr. Callan of Maynooth.” Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, vol. 25, no. 98, Irish Province of the Society of Jesus, 1936, pp. 253–69, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30097336.

- [12] Walter Lewin, 8.02x – Lect 16 – Electromagnetic Induction, Faraday’s Law, Lenz Law, Lectures by Walter Lewin. They will make you ♥ Physics @ youtube

- [13] Timeline of Catholic Clergy Scientists, via DBpedia and Wikidata