Publius Ovidus Naso (43 BCE – 17 AD), Bust of Ovid, 1st Centruy AD, Uffizi Gallery Florence, photo by Lucasaw, WikiCommons

On March 20, 43 BCE, Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso, better know as Ovid, was born. Ovid lived during the reign of Augustus. He composed both epic and elegiac poetry, some of which contributed to his exile from Rome in 8 CE. Back in high school, I remember that we had to translate from some of Ovid’s stories of his Metamorphosis from Latin. However, later we also turned to his rich and affectfully sophisticated poetry, which – for us – was much harder to translate.

“Tempus edax rerum.”

“Time, the devourer of all things.”

– Ovid, Metamorphoses

Ovid – Becoming a Poet

The only source about Ovid’s life is his own work, especially the Tristia written in exile. About his death and the place of death informs in brief words an entry in the Chronicle of Jerome. The autobiographical reliability of Ovid’s writings is partly doubted. Ovid was born in Sulmo – today Sulmona an Italian town in the province of L’Aquila of the Abruzzo region of Italy – in 43 BCE. Unlike the Roman poets Virgil and Horace, he was spared the horrors of Roman civil war; he grew up in the safety of the Pax Augusta. Ovid was the scion of a wealthy family of knights. His father sent him, together with his brother of about the same age, on the educational journey to Greece, typical of wealthy sons at that time, and then to a school of rhetoric in Rome, in preparation for the Roman career of office, the cursus honorum. There he was taught by the outstanding orators and rhetors of the time, Marcus Porcius Latro and Arellius Fuscus. It was with them that Ovid discovered his penchant for formulating verse and telling stories, and it was from Porcius Latro, who himself emerged as a poet, that Ovid later borrowed some turns of phrase in his poems.

Having reached the lowest rungs of the senatorial career of office as tresvir (probably monetalis, meaning that he held the office of master of the mint) and as decemvir stlitibus iudicandis, he abandoned this path of life. He remained connected to the legal field as a member of the courts of the centumviri (“hundred men”) and as a judge in civil cases, but then stopped all public activities to become a poet. The patron of the arts Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus accepted him into his circle of poets and promoted him.

Amores and the Art of Love

“Ut ameris, amabilis esto.”

“If you want to be loved, be lovable.”

– Ovid, Ars Amatoria

Ovid’s first work, the love poems (Amores), became a resounding success with the public; they made him the most widely read poet in Rome, at least since Horace’s death in 8 BCE. In the Amores, published between 20 and 15 BCE, first in five, then in three books, the focus is on a young woman named Corinna, who is not known to have existed as a real person in the author’s life. Ovid no longer portrays love as a sorrowful languishing, as his predecessors did, but as an amusing and frivolous game. The Ars amatoria, the “art of love” written between 1 BCE. and CE. 4, is an instructional poem in three books in which instructions are given in an ironic way on how women and men can succeed in the game of love. Love here is a technique that, like the craft of war, can be learned and mastered according to rules. Because of its provocative permissiveness, it may have aroused displeasure at the court of the emperor, who was concerned with strict morals, and thus may have been a reason for banishment (see above). The Remedia amoris (“Remedies for Love“) represent the counterpart to the art of love; they name the remedies needed to free oneself from lovesickness or to end a love affair.

Metamorphoses

After further works on the theme of love, he created his main work, the Metamorphoses. The Metamorphoses, probably written between 1 CE and 8 CE, 15 books of 700-900 verses each, is Ovid’s best-known work. It tells 250 stories of metamorphosis from ancient mythology, especially Greek mythology. The stories are connected by transitions and cross-connections in such a way that they are not just a collection, but an epic whole with a proemium at the beginning and an epilogue at the end, but without a central protagonist. The stories can be divided thematically into four blocks: Books 1-2: from the creation of the world to the sack of Europa; Books 3-6: from the building of Thebes to the Argonauts‘ voyage; Books 7-11: from the Argonauts to the Trojan kingship; 12-15: from the Trojan War to the present, the age of Augustus.

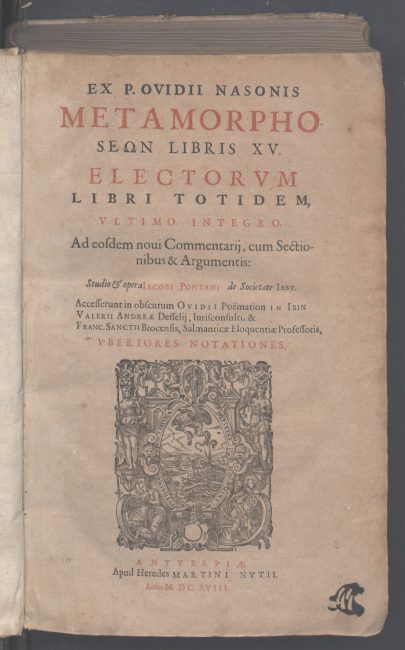

P. Ovidii Nasonis Metamorphoseon libris XV (1618)

Ovid married at a young age, but both his first and second marriages were divorced after a short period of time. His daughter probably came from the second marriage, since his third wife, to whom he remained married until his death, is never mentioned in connection with her, and both are always spoken of separately in the poems as well.

The Banishment

“Vivere me dices, sed sic ut vivere nolim.”

“Say that I live, but in such wise that I would not live.”

– Ovid, Tristia

In the fall of 8 CE, Ovid was on the island of Elba when the decision of the Emperor Augustus [1] reached him that he would be exiled to Tomi (now Constanța in Romania) on the Black Sea. Neither a trial nor a decision of the Senate legitimized this banishment, as Ovid later wrote. The banishment imposed on Ovid was – in contrast to the aquae et ignis interdictio, by which the person concerned was declared outlawed and his property confiscated – a milder form, a relegatio, for which reason he could keep his property and his civil rights. Ovid himself states that the reasons for his banishment were carmen et error, “poem and misconduct“. The poem probably refers to the Ars amatoria, which was a thorn in the flesh of the morally strict Augustus, who was very interested in restoring the traditional Roman concepts of marriage and family. However, the “misdemeanor” must have been more important, since the publication of the Ars amatoria was already eight years ago at the time of the banishment. Ovid hints at another reason in his Tristia: He had “seen something that he was not allowed to see“. It is mostly assumed in research that he was a confidant in the adultery affair of Augustus’ granddaughter Iulia. The real reason is still unclear today.

Ovid Banished from Rome (1838) by J.M.W. Turner.

Later Life and Death

“Ut desint vires, tamen est laudanda voluntas.”

“Though strength be lacking, yet the will is to be praised.”

– Ovid, Letters from the Black Sea

Ovid tried for many years to soften the emperor and achieve his recall by sending his exiled poetry to Rome. But his efforts remained unsuccessful throughout his life. During his exile from 8 to 16 CE, Ovid wrote elegies of mourning, all in epistolary form, namely five books Tristia and four books Epistulae ex Ponto (“Letters from the Black Sea“). The poet laments his hard fate, the distance from Rome and the inhospitability of the enforced place of residence. He still hopes for pardon, especially the “Letters from the Black Sea” are addressed to people from the circle of Augustus. When Augustus died, even his successor Tiberius did not recall Ovid. Not much is known about Ovid’s death. Since no allusions to events after 17 CE are found in his poetry, it is assumed that he died shortly thereafter. Addressing his wife, Ovid shared in the Tristia the inscription that was to be placed on his tomb:

Hic ego qui iaceo tenerorum lusor amorum.

Ingenio perii, Naso poeta, meo.

At tibi qui transis, ne sit grave quisquis amasti

Dicere: Nasonis molliter ossa cubent.“I who lie here, Naso, the poet, player of tender love stories, have perished of my own talent.

But to you who pass, if you ever loved, it shall not be hard to say, May Naso’s bones rest soft!”

David Nystrom: Ovid [Torrey Honors Context Lecture], [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Augustus and the Foundation of the Roman Empire, SciHi Blog

- [2] Ovid at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- [3] Works by or about Ovid at Internet Archive

- [4] English translations of Ovid’s Amores with introductory essay and notes by Jon Corelis

- [5] William Turpin (2016). Ovid, Amores (Book 1). Open Book Publishers

- [6] Works by or about Ovid at Wikisource

- [7] Ovid at Wikidata

- [8] The Ovid Project: Metamorphising the Metamorphoses (Illustrations by Johann Whilhelm Baur (1600–1640) and anonymous illustrations from George Sandy’s edition of 1640.)

- [9] Timeline of Roman Poets, via Wikidata and DBpedia

- [10] David Nystrom: Ovid [Torrey Honors Context Lecture], BiolaUniversity @ youtube