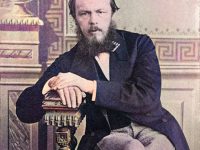

Maxim Gorky (1868-1936)

On June 18, 1936, Russian writer Alexei Maximovich Peshkov, better known as Maxim Gorky passed away. He was the founder of the Socialist realism literary method and a political activist. He worked in many jobs during an impoverished and abusive childhood before finding fame and fortune as a writer. Initially a Bolshevik supporter, Gorky became a critic when Vladimir Lenin seized power. However, Gorky later served as a Soviet advocate and headed the Union of Soviet Writers.

“There’s a little book I’m thinking of writing — “Swan Song” is what I shall call it. The song of the dying. And my book will be incense burnt at the deathbed of this society, damned with the damnation of its own impotence.”

– Maxim Gorky, Foma Gordeyev (1899)

Maxim Gorky’s Youth

Gorky was born as Alexei Maximovich Peshkov in Nizhny Novgorod, and became an orphan at the age of eleven. He was brought up by his grandparents and knew the Russian working-class background intimately, for his grandfather afforded him only a few months of formal schooling, sending him out into the world to earn his living at the age of eight. In 1880 at age twelve, Gorky ran away from home. After an attempt at suicide in 1887, he travelled on foot across the Russian Empire for five years, changing jobs and accumulating impressions used later in his writing.

From Journalism to Literature

As a journalist working for provincial newspapers, he began using the pseudonym “Gorky” (from горький; literally “bitter”) in 1892. The name reflected his simmering anger about life in Russia and a determination to speak the bitter truth. Gorky’s first book Essays and Stories in 1898 enjoyed a sensational success, and his career as a writer began. Gorky saw in literature less an aesthetic practice than a moral and political act that could change the world. He described the lives of people of the lowest birth and on the margins of society, revealing their hardships and humiliations, but also their inward spark of humanity. In 1899 he published Twenty-Six Men and a Girl, describing the labour conditions in a bakery, which is often regarded as his best short story. Gorky’s reputation quickly soared and he began to be spoken of almost as an equal of Leo Tolstoy [4] and Anton Chekhov.[5]

A Marxist World View

“There — you say — truth! Truth doesn’t always heal a wounded soul.”

– Maxim Gorky, The Lower Depths (1902)

By 1899, he was openly associating with the emerging Marxist social-democratic movement, which helped make him a celebrity among both the intelligentsia and the growing numbers of “conscious” workers. He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime and was arrested many times. Gorky befriended many revolutionaries and became a personal friend of Vladimir Lenin after they met in 1902. In 1902, Gorky was elected an honorary Academician of Literature, but Tsar Nicholas II ordered this annulled. In protest, Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko left the Academy. Gorky followed the Bolshevik wing following a party split in 1903, though he was never an official party member. His most influential writings in these years were a series of political plays, most famously The Lower Depths (1902). Gorky was imprisoned for his actions during the Russian Revolution of 1905. He left Russia in 1906, visiting the United States with his mistress on behalf of the Bolsheviks who had sent him on a fund-raising trip, before moving to a villa on the Italian island of Capri, where he spent most of the next seven years.

Amnesty and Emigration to Italy

An amnesty granted for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty allowed Gorky to return to Russia in 1913, and he was living there when the Bolsheviks and Vladimir Lenin seized control of the country in 1917. Gorky objected to the undemocratic tactics that were used in this takeover and frequently wrote in his newspaper, New Life, about the violence and repression that Russia experienced under Lenin’s rule. Gorky was silenced in 1918 when the newspaper was shut down. For his criticism of the Bolsheviks and due to health reasons he left Russia again for Italy, where he wanted to cure his tuberculosis. Gorky spent most of the period from 1921 to 1928 living abroad, mostly in Sorrento, Italy, where he wrote several successful books. In the decade ending in 1923 Gorky’s greatest masterpiece appeared, the autobiographical trilogy, which is one of the finest autobiographies in Russian. It describes Gorky’s childhood and early manhood and reveals him as an acute observer of detail, with a flair for describing his own family, his numerous employers, and a panorama of minor but memorable figures. [2]

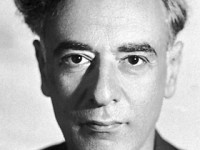

Returning Home on Stalin’s Personal Invitation

“It is quiet and peaceful here, the air is good, there are numerous gardens, and in them nightingales sing and spies lurk under the bushes”

– Maxim Gorky in a letter to Anton Chekov

In 1932 Joseph Stalin, who had taken control of the Soviet Union after Lenin’s death, personally invited him to return for good, an offer he accepted. Not only was Gorky an acclaimed writer, but having him inside the country would also make it easier to keep an eye on his activities. With the increase of Stalinist repression and especially after the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, Gorky was placed under unannounced house arrest in his house near Moscow. On June 18, 1936, Gorky died at age 68.

Leitmotiv in Russian Novels of the 19th and 20th Centuries, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Maxim Gorky Biography at biography.com

- [2] Maxim Gorky at Britannica online

- [3] Charles Dickens – Famous Writer and Critic of the Victorian Era, SciHi Blog

- [4] If the world could write by itself, it would write like Tolstoy, SciHi Blog

- [5] Anton Chekov and the Birth of early Modernism in the Theatre, SciHi Blog

- [6] Works by or about Maxim Gorky at Internet Archive

- [7] Newspaper clippings about Maxim Gorky in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [8] Maxim Gorki at Wikidata

- [9] Leitmotiv in Russian Novels of the 19th and 20th Centuries, WoodrowWilsonCenter @ youtube

- [10] Tovah Yedlin. Maxim Gorky: A Political Biography

- [11] Figes, Orlando (June 1996). “Maxim Gorky and the Russian revolution”. History Today. 46 (6): 16.

- [12] Timeline for Maxim Gorky, via Wikidata