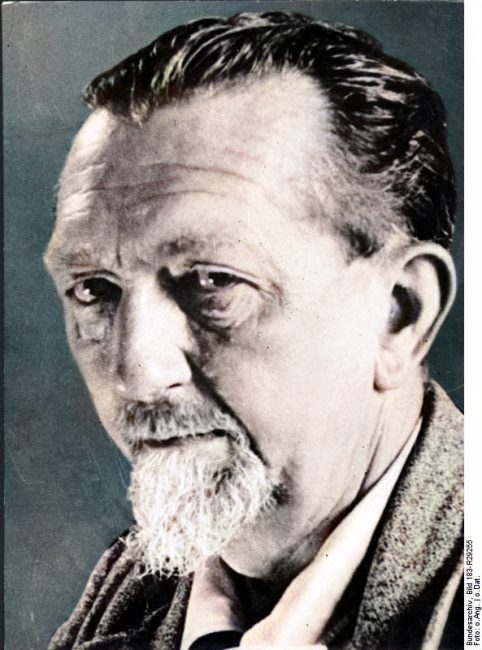

Leo Frobenius (1873-1938), Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R29255 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

On June 29, 1873, German ethnologist and archaeologist Leo Viktor Frobenius was born. He proposed a theory that culture evolves through stages of youth, maturity, and age. He helped to spread knowledge of West African art and culture throughout Europe. He made a series of twelve major expeditions throughout Africa, gathering knowledge of art and culture, travelling across the deserts, savannahs and rain forests of Africa and South Africa, the River Nile and the shores of the Red Sea.

“Only those who seek to understand the others, but not those who reject each other, recognize the essential.”

– Leo Frobenius

The Son of a Prussian Officer

As the son of the Prussian officer Hermann Frobenius and grandson of Heinrich Bodinus, director of the Berlin Zoological Garden, Leo Frobenius spent an unstable childhood, left high school without diploma and completed an apprenticeship as a merchant. As an autodidact he turned early to ethnology, was a volunteer at various museums and founded his “Afrika-Archiv” in Munich in 1898, which he later renamed the Institute for Cultural Morphology. With his essay On the origin of African culture (Ursprung der afrikanischen Kultur), also published in 1898, he founded a theory of culture, Kulturkreislehre), from which he later turned away again because it seemed all too mechanistic to him.

Expeditions to Africa

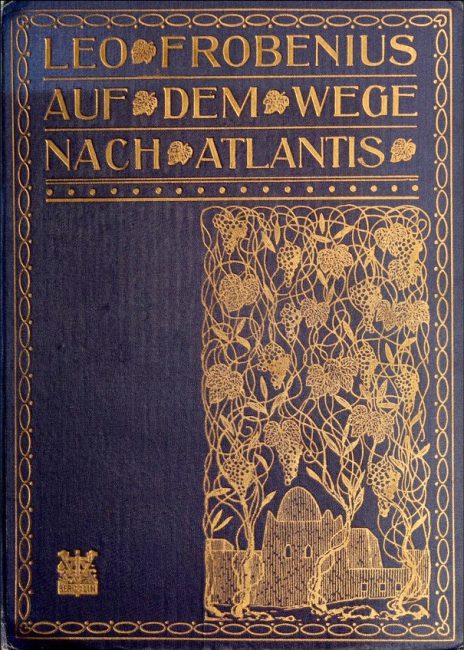

Leo Frobenius’ first African expedition took place in 1904. He traveled to the Kasai district in Congo, formulating the African Atlantis theory during his journeys. The theory is a now-discredited hypothetical civilization thought to have once existed in southern Africa, initially proposed Leo Frobenius around 1904. This lost civilization was conceived to be the root of African culture and social structure. Frobenius assumed that a white civilization must have existed in Africa prior to the arrival of the European colonizers. Until 1918 he travelled in the western and central Sudan, and in northern and northeastern Africa. In 1920 he founded the Institute for Cultural Morphology in Munich. In 1932 he became honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt, and in 1935 director of the municipal ethnographic museum.

Cover page from Expeditionsbericht der Zweiten Deutschen Inner-Afrika-Expedition (1907-09) Auf dem Wege nach Atlantis

Cultural Morphology

During the late 1890s, Frobenius defined several ‘culture areas‘, being cultures showing similar traits that have been spread by diffusion or invasion. He established the term paideuma, trying to describe a manner of creating meaning, that was typical of certain economic structures. Then, it was attempted to reconstruct some kind of world view of hunters, early planters, and builders. At the same time he developed the basic features of his “cultural morphology”, which understood the individual cultures as organisms, whereby he was influenced by Oswald Spengler,[6] among others. Central to his theory is the concept of “Paideuma“, the “cultural soul”, which he also used as the title for the journal he founded in 1938.

Later Years

At the beginning of World War I, Frobenius led a secret mission to neutral Abyssinia to organize an uprising in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. However, the Italian authorities in Massaua (Eritrea) banned further travel and Frobenius returned to Europe. Frobenius then traveled with the German army for scientific purposes in Romania. Frobenius‘ team performed archeological and ethnographic studies and documented the ‘daily life’ of the inmates of the Slobozia prisoner camp. Later, Frobenius taught at the University of Frankfurt and the city acquired his collection of 4700 prehistorical African stone paintings. The local institute of ethnology where the paintings are currently stored was named the Frobenius Institute in his honour in 1946.

Ethnosociology Lecture 2. The German school. Dugin, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Frobenius Institute at Frankfurt am Main

- [2] Leo Frobenius at the German National Library

- [3] Works of Leo Frobenius (in German) via Wikisource

- [4] Robert Fisk, The German Lawrence of Arabia had much to live up to – and failed

- [5] Leo Frobenius at Wikidata

- [6] Oswald Spengler and the Decline of the West, SciHi Blog

- [7] Newspaper clippings about Leo Frobenius in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [8] “German Discovers Atlantis In Africa; Leo Frobenius Says Find of Bronze Poseidon Fixes Lost Continent’s Place”. The New York Times. 30 January 1911.

- [9] Ethnosociology Lecture 2. The German school. Dugin, ARCTUR @ youtube

- [10] Frobenius, Leo Viktor. Hessische Biografie. (Stand: 12. Januar 2020). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- [11] Helmut Straube: Frobenius, Leo. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 5, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1961, ISBN 3-428-00186-9, S. 641 f.

- [12] Kuba, Richard (2020). “The Expeditions of Leo Frobenius between Science and Politics: Nigeria 1910-1912 ”, in BEROSE – International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology, Paris.

- [13] Timeline of Historians of Africa, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #46 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Leo Frobenius and the Theory of Cultural MorphologySciHi Blog - Roots Afrikiko