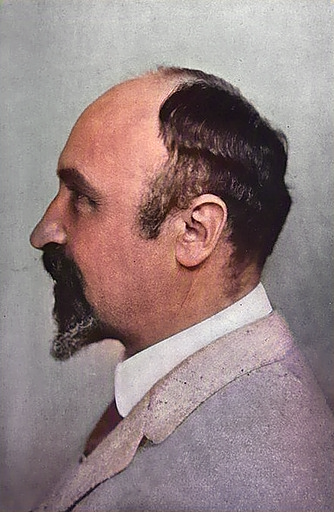

Leo Baekeland (1863 – 1944)

On November 14, 1863, Belgian-born American chemist Leo Henricus Arthur Baekeland was born. His invention of Bakelite, an inexpensive, nonflammable, versatile, and popular plastic, marked the beginning of the modern plastics industry. Back in the eighties and nineties, the phrase plastic-fantastic was coined to describe a cheap item that more than often broke when you started using it because the early day plastic was so brittle. However, bakelite was different…

The Velox Photography Paper

The son of the shoemaker Charles Baekeland developed an early interest in science and economics. As a teenage student at night school, he received awards in chemistry, physics and economics. A scholarship enabled him to study chemistry at the University of Ghent from 1880. In 1884, at the age of barely 20, he received his doctorate. In addition to teaching at a secondary school, he worked as an associate professor of chemistry at the University of Ghent from 1888. In 1889 he married Celine Swarts, the daughter of his former professor of chemistry, Theodore Swarts. He continued his studies of chemistry in New York City, England, Scotland, and Germany. He was then persuaded to stay in the United States and he began working at a New York photographic supply house, which inspired him for later developments, especially Velox, an improved photographic paper that could be developed in gaslight rather than sunlight. [1]

First Experiments with Polymers

In 1899, he sold the rights to a photographic paper he had developed for one million dollars to the Eastman Kodak company. This money enabled him to continue his studies in his own private laboratory and hire the assistant Nathaniel Thurlow. Both knew of the great potential phenol-formaldehyde resins and they read about the experiments by Adolf von Baeyer [4] and Werner Kleeberg. They reported that when he mixed phenol, a common disinfectant, with formaldehyde, it formed a hard, insoluble material that ruined his laboratory equipment, because once it has formed, it could not be removed. The produced substance was described as a hard amorphous mass, infusible and insoluble and thus of little use. Further scientists, including Adolf Luft performed several experiments in order to create a commercially viable plastic molding compound. However, none of them was known to have created a useful product.

Controlled Processing

At that time, many chemists began recognizing that many of the natural resins and fibers useful for coatings, adhesives, and woven fabrics were polymers even though its molecular structure was not completely known. When Baekeland and his assistant started to investigate the reactions of phenol and formaldehyde, they produced ‘Novolak‘, but unfortunately, this was never really successful. The scientists moved on to developing a phenol-formaldehyde binder for asbestos. A self-developed autoclave (bakelizer), which can be optionally heated and cooled, enabled him to control the temperature of the chemical reaction under overpressure. In numerous experiments, he determined the variables influencing the course of the reaction and was able to synthesize a polymer that produced a hard moldable plastic when it was mixed with certain fillers and Bakelite was born. [1,2, 3]

Bakelite

Bakelite had the advantage, that it could be molded quickly. Also, it was known for its extraordinarily high resistance and thus, became a popular material for the emerging electrical and automobile industries. Soon, Bakelite was integrated in numerous areas of living. Jewellery was made out of it as well as telephones, or even billiard balls. [1] The invention of Bakelite marks the beginning of the age of plastics. Bakelite was the first plastic invented that retained its shape after being heated. Soon its applications spread to most branches of industry.

Later Years

In 1909, he received the important heat-pressure patent. In the following years, patent disputes arose which he was able to win. At the end of 1910, he and his opponents founded the General Bakelite Company, which was taken over by Union Carbide in 1939. In the years after 1910, Baekeland held numerous honorary offices in addition to his work as president of the Bakelite Corporation.

Honors

Baekeland was awarded numerous honors for his services: In 1910, he received the William H. Nichols Medal of the American Chemical Society, in 1913 the Willard Gibbs Medal of the American Chemical Society, and in 1940 the Franklin Medal of the Franklin Institute. Baekeland was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1935 and to the National Academy of Sciences in 1936. In the same year he became an honorary fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He is on the “List of the 20 Greatest Thinkers and Scientists of the 20th Century” published by the American Time Magazine on March 29, 1999.

Leo Baekeland died of a stroke in a sanatorium in Beacon, New York, in 1944 at age 80.

Nicolas Vogel, Polymer Science and Processing 01: Introduction [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Leo Baekeland at the Chemical Heritage Foundation

- [2] Leo Hendrick Baekeland and the Invention of Bakelite

- [3] Leo Baekeland at History of Plastic

- [4] Adolf von Baeyer and the Synthesis of Indigo, SciHi Blog

- [5] Time, Mar. 29, 1999, Chemist LEO BAEKELAND

- [6] Kettering, Charles Franklin (1946). Biographical memoir of Leo Hendrik Baekeland, 1863–1944. Presented to the academy at the autumn meeting, 1946. National Academy of Sciences (U.S.).; Biographical memoirs. p. 206.

- [7] Leo Baekeland at Wikidata

- [8] Nicolas Vogel, Polymer Science and Processing 01: Introduction, the Vogel Lab @ youtube

- [9] Craig, John A. (April 1916). “Leo Hendrik Baekeland: The Latest Winner Of The Perkin Medal”. The World’s Work: A History of Our Time. XXXI: 651–655.

- [10] Timeline of Belgian Inventors, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #14 | Whewell's Ghost