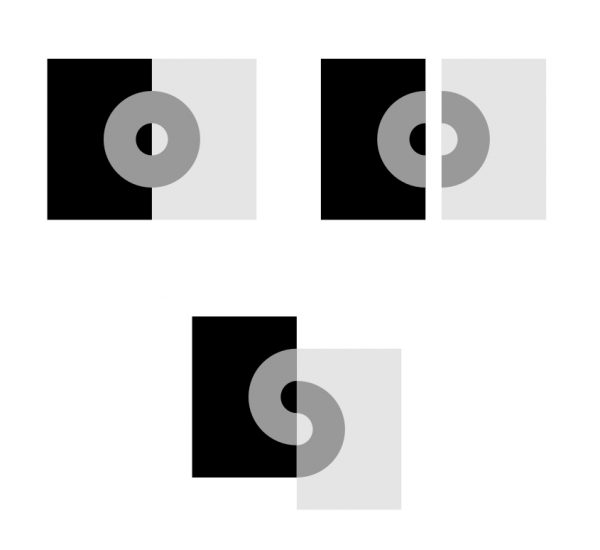

Koffka Ring – Koffka offered an example of how simultaneous contrast can be manipulated by changing spatial configuration. The upper right ring appears almost uniform in color. When the stimulus is split in two, as shown in the upper left, the two half-rings appear to be different shades of gray. The two halves now have separate identities, and each is perceived within it own context. A novel variant that involves transparency is shown below. The left and right half-blocks are slid vertically, and the new configuration leads to a very different perceptual organization and a strong lightness illusion.

On March 18, 1886, German psychologist Kurt Koffka was born. Koffka along with Max Wertheimer and his close associates Wolfgang Köhler established Gestalt psychology. Koffka’s interests were wide-ranging, and they included: Perception, hearing impairments in brain-damaged patients, interpretation, learning, and the extension of Gestalt theory to developmental psychology.

“Conduct, of course, is possible without science. Humans carried on in their daily affairs long before the first spark of science had been struck. And today there are millions of people living whose actions are not determined by anything we call science. Science, however, could not but gain an increasing influence on human behaviour. To describe this influence roughly and briefly will throw a new light on science. Exaggerating and schematizing the differences, we can say: in the prescientific stage man behaves in a situation as the situation tells him to behave. To primitive man each thing says what it is and what he ought to do with it: a fruit says, “Eat me”; water says, “Drink me”; thunder says, “Fear me,” and woman says, “Love me.””

— Kurt Koffka, Principles of Gestalt Psychology, 1935

Youth and Education

Kurt Koffka was born on March 18, 1886 in Berlin, Germany, to his father Emil Koffka, a lawyer and his mother Luis Levy, a protestant of Jewish descent. Early in Koffka’s life his biologist uncle aroused his interests in the fields of philosophy and science. He learned how to speak English from an English governess and from 1892 to 1903 was educated at the Wilhelms-Gymnasium, considered one of the best-known schools in the city. He spent the year 1903-1904 at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland where he developed a strong fluency in English. From 1904-1907 Koffka was enrolled in the University of Berlin as a psychology student breaking with the family tradition, but he found himself at home in this field and earned his PhD there in 1909 as a student of Carl Stumpf with a thesis on Experimental Untersuchungen zur Lehre vom Rhythmus (1909; Experimental Investigations of Rhythm). In 1909, Koffka married Mira Klein, who had been an experimental subject in his research. In 1923 they were divorced and he married Elisabeth Ahlgrimm who had recently finished her Ph.D at Giessen. Three years later, in 1926, they divorced and Koffka remarried Mira, but in 1928 they were divorced for the second time and he remarried Elisabeth.

The Birth of Gestalt Psychology

During 1908/1909 he was assistant in the psychological laboratory of Johannes von Kries in Freiburg, and in 1909/1910 he was assistant in Wiirzburg, first to Oswald Külpe and then, after Külpe left for Bonn, to Karl Marbe.[2] Koffka was already working at the University of Frankfurt when Max Wertheimer arrived in 1910 and invited Wolfgang Koffka to participate as a subject in his research on the Phi phenomenon [3]. This work led to Wertheimer’s paper on the perception of movement that marked the birth of gestalt psychology in 1912.[2,3] The movement itself came into being as a protest against the reductionist theories that were then current. These theories assumed that if psychology was to be a science, it must find ways of analyzing its subject matter into constituent elements. Experience was taken as the starting point, but the elements into which it was broken down were often completely lacking in the quality of the experience that was being studied. For example, until Wertheimer’s studies, movement was commonly treated as the experience of a succession of states of rest, states that showed none of the essential character of movement.[2]

What is Gestalt Psychology?

Gestalt psychology is an attempt to understand the laws behind the ability to acquire and maintain meaningful perceptions in an apparently chaotic world. The central principle of gestalt psychology is that the mind forms a global whole with self-organizing tendencies. However, the assumed physiological mechanisms on which Gestalt theory rests are poorly defined and support for their existence is lacking. In the study of perception, Gestalt psychologists stipulate that perceptions are the products of complex interactions among various stimuli. Contrary to the behaviorist approach to focusing on stimulus and response, gestalt psychologists sought to understand the organization of cognitive processes.

Academic Career

In 1911 Koffka moved to the University of Giessen and in 1914 became Privatdozent. During the First World War, he worked for the military in a position that later lead him to a professorship and to becoming part of the Berlin School of experimental psychology. In 1924 Koffka travelled to the United States, where he was a visiting professor at Cornell University from 1924 to 1925, and two years later at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The Growth of the Mind

In 1913, Koffka began editing a series of publications entitled Beiträge zur Psychologie der Gestalt (Contributions to the Psychology of the Gestalt). American psychologists were exposed to Gestalt psychology in 1922 in his article entitled: Perception: An Introduction to the Gestalt-Theorie, which appeared in the Psychological Bulletin. One of Koffka’s major contributions was The Growth of the Mind in 1921. Koffka wanted to provide some sort of evidence supporting Gestalt psychology to the field of developmental psychology. In 1935 he wrote Principles of Gestalt Psychology, which helped members of the Gestalt group and their students bring their Gestalt point of views together. It is also most notable for topics such as, Perception, Learning, and Memory.

Individual Sensations and the Human Mind

Koffka claimed that the human mind naturally organizes individual sensations and experiences into meaningful wholes. In one of the first articles in English that Koffka wrote in 1922, he proposed his hypothesis of infant perception, saying that infants at first cannot distinguish individual objects, but perceive everything holistically. As they grow older, infants learn to discriminate and respond to individual objects. Thus, instead of building up meaning from separately perceived elements, Koffka suggested that we first perceive an impression of the whole environment and then gradually distinguish and separate out the distinct objects within it, often never noticing the individual elements that make up these objects.[4]

Sensomotoric Learning

Koffka believed that most of early learning is what he referred to as, “sensorimotor learning,” which is a type of learning which occurs after a consequence. For example, a child who touches a hot stove will learn not to touch it again. Koffka also believed that a lot of learning occurs by imitation, though he argued that it is not important to understand how imitation works, but rather to acknowledge that it is a natural occurrence. According to Koffka, the highest type of learning is ideational learning, which makes use of language. Koffka notes that an important time in children’s development is when they understand that objects have names.

In 1927, Koffka accepted a position at the Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, which he retained until his death in 1941 from Coronary thrombosis.

Gestalt Principles. How psychology influences your design strategy, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Kurt Koffka, German psychologist , at Britannica Online

- [2] “Koffka, Kurt.” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. . Encyclopedia.com

- [3] Max Wertheimer and Gestalt Psychology, SciHi Blog, April 15, 2016.

- [4] Kurt Koffka, in The New World Encyclopaedia

- [5] Gestalt psychology website of the international Society for Gestalt Theory and its Applications – GTA

- [6] Kurt Koffka, (1922) Perception: An Introduction to the Gestalt Theorie

- [7] Kurt Koffka at Wikidata

- [8] Gestalt Principles. How psychology influences your design strategy, Art with Kunstler @ youtube

- [9] Timeline of German Psychologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata