Justus Liebig (1803 – 1873)

On May 12, 1803, German chemist Justus Freiherr von Liebig was born, who made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry. He is probably best known as the “father of the fertilizer industry” for his discovery of nitrogen as an essential plant nutrient.

The acquisition of a new truth is like the acquisition of a new sense, which renders a man capable and recognizing a large number of phenomena that are hidden from another, as they were from him originally. – Justus Liebig

Early Years of Justus Liebig

Justus Liebig’s father was also a chemist and he began his experiments with his father’s equipment in very early childhood years. Even though Justus Liebig was a curious student, he was taken out of school very early due to his limited abilities. The apprenticeship at a local pharmacy he began also ended quickly after setting the facility’s attic on fire with silver fulminate. Still, Liebig’s interest in chemistry grew and he began teaching himself from library books. He worked with his father for the next two years, then attended the University of Bonn, studying under Karl Wilhelm Gottlob Kastner, a business associate of his father. When Kastner moved to the University of Erlangen, Liebig followed him. In late 1822 Liebig went to study in Paris on a grant obtained for him by Kastner from the Hessian government. He worked in the private laboratory of Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac.[6] His talents were finally noticed and after Alexander von Humboldt read several of Liebig’s works that highly impressed him, he became professor of chemistry in Gießen.[4] Liebig’s appointment was part of an attempt to modernize the University of Giessen and attract more students. He received a small stipend, without laboratory funding or access to facilities.

Liebig’s Research and Teaching Institute

Liebig and several associates proposed to create an institute for pharmacy and manufacturing within the university. The Senate, however, uncompromisingly rejected their idea. They ruled that any such institution would have to be a private venture. This decision actually worked to Liebig’s advantage. As an independent venture, he could ignore university rules and accept both matriculated and non-matriculated students. Liebig was one of the first chemists to organize a laboratory in its present form, engaging with students in empirical research on a large scale through a combination of research and teaching. His methods of organic analysis enabled him to direct the analytical work of many graduate students. In 1833, Liebig was able to convince chancellor Justin von Linde to include the institute within the university. In 1839, he obtained government funds to build a lecture theatre and 2 separate laboratories.

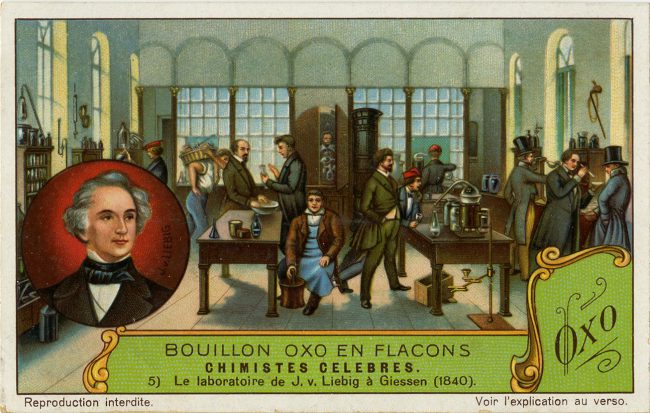

Liebig’s Laboratory, Chimistes Celebres, Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company Trading Card, 1929

Kaliapparat

In 1852, the University of Munich offered Liebig a position at the chemical institute, which he accepted. Justus Liebig was able to extent his chemical studies in chemistry and managed to extent his reputation even further through the years, making him to one of the most important European chemists. During his scientific career, Justus Liebig often noticed the bad quality of common analyzing methods and improved several instruments significantly. The kaliapparat, developed by Liebig helped him and his scientific employees to achieve important tasks in analyzing the compounds of plant’s and animal’s cells, leading to the foundations of organic chemistry. Liebig’s kaliapparat simplified the technique of quantitative organic analysis and rendered its routine. His method of combustion analysis was used pharmaceutically, and certainly made possible many contributions to organic, agricultural and biological chemistry.

Liebig and Agriculture

By the 1840s, Liebig was attempting to apply theoretical knowledge from organic chemistry to real-world problems of food availability. His book Die organische Chemie in ihrer Anwendung auf Agricultur und Physiologie (Organic Chemistry in its Application to Agriculture and Physiology) (1840) promoted the idea that chemistry could revolutionize agricultural practice, increasing yields and lowering costs. It was widely translated, vociferously critiqued, and highly influential. Liebig’s book discussed chemical transformations within living systems, both plant and animal, outlining a theoretical approach to agricultural chemistry. Liebig argued against prevalent theories about role of humus in plant nutrition, which held that decayed plant matter was the primary source of carbon for plant nutrition. Fertilizers were believed to act by breaking down humus, making it easier for plants to absorb. Associated with such ideas was the belief that some sort of “vital force” distinguished reactions involving organic as opposed to inorganic materials.

The Year without Summer

1816, the year without summer not only inspired Karl Drais to develop his famous mechanical horse, also Liebig wanted to prevent hunger periods like these through supporting agriculture with chemistry. [5] His first official works followed in the 1840’s and astonished not only chemists, but academics across the continent. In his works, he explained the meaning and possible use of fertilizers, which were translated into about 34 languages. Due to Liebig’s achievements the harvests of the 19th century were improved significantly.

To prevent the starvation of newborns in poor families, Justus Liebig developed and distributed baby food and several years later he managed to create baking powder to substitute the easy perishable yeast used for baking bread.

Justus Liebig died in Munich in 1873, at age 69.

Justus von Liebig’s Life Saving Extract, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Liebig Museum

- [2] Deutsches Historisches Museum

- [3] The University of Houston

- [4] On the Road with Alexander von Humboldt, SciHi Blog

- [5] Karl Drais and the Mechanical Horse, SciHi Blog

- [6] Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and his Work on Gases, SciHi Blog

- [7] Justus von Liebig at Wikidata

- [8] Justus von Liebig’s Life Saving Extract, Storytelling TM @ youtube

- [9] Knapp, G. F. (1903), “Zur Hundertsten Wiederkehr: Justus von Liebig nach dem Leben gezeichnet”, Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, 36 (2): 1315–1330

- [10] Liebig, Georg von (1890), “Nekrolog: Justus von Liebig. Eigenhändige biographische Aufzeichnungen”, Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft, 23 (3): 817–828

- [11] Newspaper clippings about Justus von Liebig in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [12] Priesner, Claus (1985), “Liebig, Justus Freiherr von”, Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 14, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 497–501

- [13] Justus von Liebig Timeline via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol: #40 | Whewell's Ghost