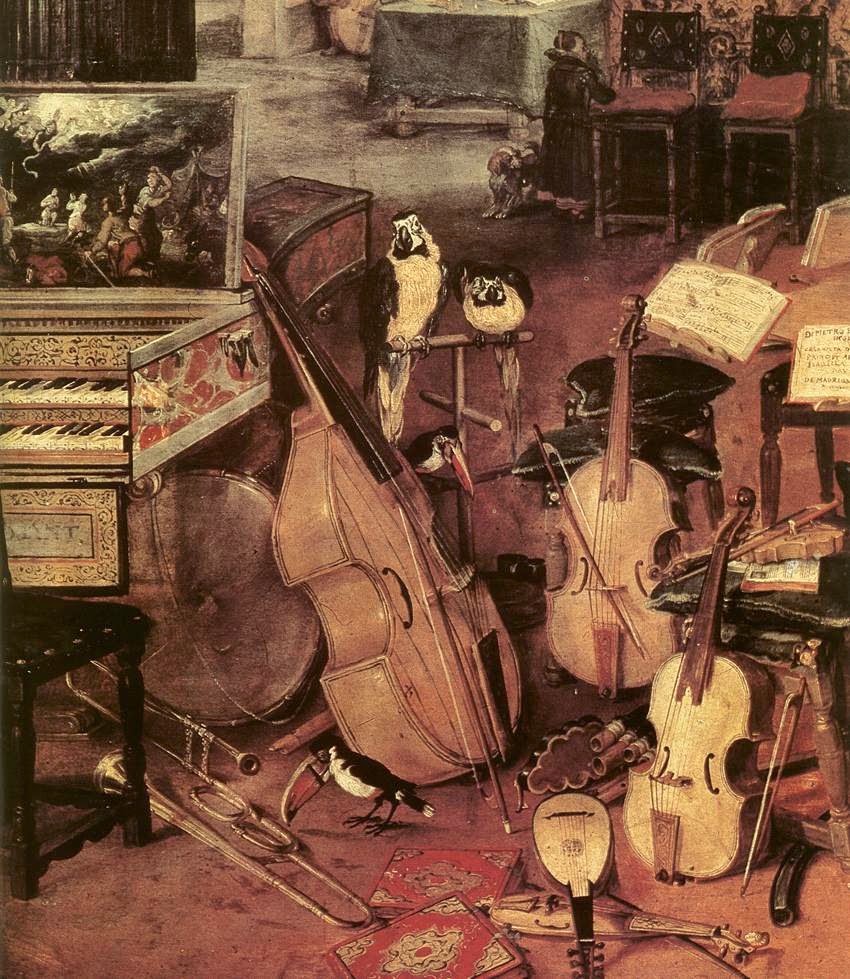

Baroque Musical Instruments by Breughel, unfortunately there is no portrait of Joseph Sauveur

On March 24, 1653, French mathematician and physicist Joseph Sauveur was born. Sauveur is known principally for his detailed studies on acoustics, a term he also has coined for the first time.

Joseph Sauveur – Early Years

Joseph Sauveur was the son of a provincial notary in La Fléche, France. Despite a hearing and speech impairment that kept him totally mute until he was seven, Joseph benefited from a fine education at the Jesuit College of La Flèche, where his favorite subject was mathematics. Even ever after Joseph was obliged to speak very slowly and with difficulty. He very early discovered a great turn for mechanics and read with greediness books of arithmetic and geometry. Being intended for the church, he applied himself for a time to the study of philosophy and theology. At seventeen, his uncle agreed to finance his studies in philosophy and theology at Paris. Joseph, however, during his course of philosophy, he learned the first six books of Euclid in the time of a month [3], without the help of a master, and turned to anatomy and botany.

The Study of Physics

As he had an impediment in his voice, he gave up a church career and applied himself to the study of physics. As this was against the wishes of his uncle, from whom he drew his principal resources, Sauveur determined to devote himself even more to his favourite study, so as to be able to teach it for his support. Despite his handicap, Sauveur at age 23 managed to teach mathematics to the French Dauphine’s pages and also to a number of princes of the Royal court, among them Eugene of Savoy. He had not yet read the geometry of Descartes,[4] but he managed to make himself master of it in an inconceivably small space of time. By 1680, he was something of a pet at court, where he gave anatomy courses. “Basset” being a fashionable game at that time, the marquis of Dangeau asked him for calculating the odds, which gave such satisfaction, that Sauveur had the honor to explain them to the king and queen.

Hydrostatics and the Game of Chances

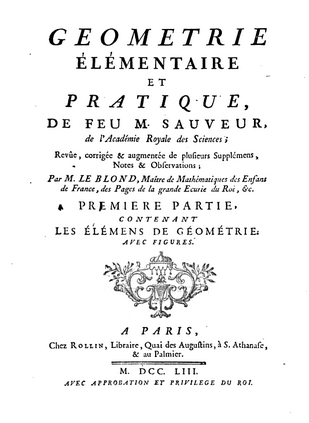

Sauveur’s enormous aptitude in mathematics and geometry, along with his serendipititious mathematical work on games of chance at a time when nobles and courtiers spent much of their time at Versailles gambling, led to a rapid accumulation of rich and powerful patrons, students, and positions. In 1681, Sauveur did the mathematical calculations for a waterworks project for the “Grand Condé’s” estate at Chantilly, working with Edmé Mariotte, the “father of French hydraulics”. Condé became very fond of Sauveur and severely reprimanded anyone who laughed at the mathematician’s speech impediment. During his stay in Chantilly, Sauveur did his work on hydrostatics. During the summer of 1689, Sauveur was chosen to be the science and mathematics teacher for the Duke of Chartres, Louis XIV‘s nephew. For the prince, he drew up a manuscript outlining the “elements” of geometry and, in collaboration with Marshal Vauban,[8] a manuscript on the “elements of military fortification” and, in order to join practice with theory, he went to the siege of Mons in 1691, where he continued all the while in the trenches. In 1686 Sauveur obtained the mathematics chair at the Collège de France, which granted him a rare exemption: since he was incapable of reciting a speech from memory, he was permitted to read his inaugural lecture.

Frontpage of Geometrie (1753) by Joseph Sauveur, edited and augmented by Guillaume Le Blond

The Science of Sound

Circa 1694, Sauveur began working with Émile Loulié, a musician and teacher at the royal court, on “the science of sound“, that is, acoustics. This is really something extraordinary taking in mind Sauveur’s handicapped condition. He had neither a voice nor hearing, yet he could think only of music. For all acoustical experiments he was reduced to borrowing the ear of someone else. Sauveur is known principally for his detailed studies on a new branch of physics called acoustics. Indeed, he has been credited with coining the term acoustique, which he derived from the ancient Greek word ακουστός, meaning “able to be heard“. His work involved researching the correlation between frequency and musical pitch, and he conducted studies on subjects such as the vibrating string, tuning pitch, harmonics, ranges of voices and musical instruments.

Further Research in Acoustics

If particular, Sauveur also determined how to identify the pitch of a note by assessing the frequency of its vibration. He also asserted that harmonics are the component parts of all musical sound. In particular Saveur’s system of 43 meridians, 301 heptameridians, and 3010 decameridians, the equal logarithmic units into which he divided the octave, made possible not only as close a specification of pitch as could be useful for acoustical purposes, but also provided a satisfactory approximation to the just scale degree as well as to 1/5-comma meantone temperament.[7] Although Sauveur was not the first to observe that tones of the harmonic series are emitted when a string vibrates in aliquot parts, he did give a table expressing all the values of the harmonics within the compass of five octaves and thus brought order to earlier scattered observations. He also noted that a string may vibrate in several modes at once, and applied his system and his observations to an explanation of the leaping tones of the marine-trumpet and the hunting horn.[7]

Later Years

In 1696, Saveur had been elected to the French Royal Academy of Sciences and most of his work on acoustics was therefore done under its aegis. Sauveur, whom a contemporary described as “over-obliging, gentle, and humorless”, was declared a “pensioned veteran” of the Academy in on March 4, 1699. It was not until 1701 that Sauveur presented the results of his research to the Academy. The presentation was studded with jibes about musicians and their closed minds. In 1703, Marquis de Vauban having been made marshal of France, proposed Sauveur to the king as his successor in the office of examiner of the engineers, to which the king agreed, and honored him with a life-long pension. Sauveur was of an obliging disposition, and of a good temper; humble in his deportment, and of simple manners. He passed away in 1716.

Tiku Majumdar, Musical Acoustics and Sound Perception, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Joseph Sauveur in Chalmer’s Biographies, 1812

- [2] Christopher Baker (eds.): Absolutism and the Scientific Revolution, 1600-1720: A Biographical Dictionary, p. 338

- [3] Euclid – the Father of Geometry, SciHi Blog, January 30, 2015.

- [4] Cogito Ergo Sum – René Descartes, SciHi Blog, March 31,2013

- [5] Robert E Maxham , The contributions of Joseph Sauveur (1653-1716) to acoustics, University of Rochester, NY, ISA, 1976.

- [6] Joseph Sauveur at Wikidata

- [7] Joseph Saveur at Musicologie.org

- [8] Vauban or the Art of Fortress Construction, SciHi Blog

- [9] Tiku Majumdar, Musical Acoustics and Sound Perception, 2011, Williams College @ youtube

- [10] Adam Fix, “A Science Superior to Music: Joseph Sauveur and the Estrangement between Music and Acoustics,” Physics in Perspective 17, no. 3 (2015): 173–97.

- [11] Fontenelle: Éloge de Joseph Sauveur. in: Histoire de l’Académie Royale des sciences 1716.

- [12] Time line of physicist musicologists, via Wikidata