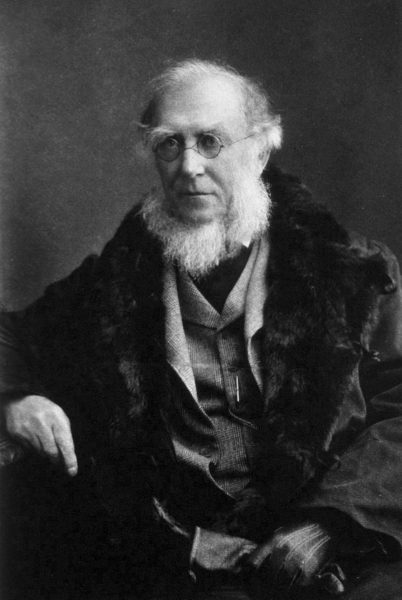

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker OM, GCSI, CB, FRS (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911)

On June 30, 1817, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker was born, one of the greatest British botanists and explorers of the 19th century. Hooker was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin‘s [4] closest friend. Furthermore, he was assistant on Sir James Ross‘s [3] Antarctic expedition and whose botanical travels to foreign lands included India, Palestine and the U.S., from which he became a leading taxonomists in his time.

“All I ever aim to do is to put the Development hypothesis in the same coach as the creation one. It will only be a question of who is to ride outside & who in after all.”

— Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, Letter to Asa Gray (31 May 1859).

Joseph Dalton Hooker – Early Years

Joseph Dalton Hooker was born in Halesworth, Suffolk, England, the second son of the famous botanist Sir William Jackson Hooker, Regius Professor of Botany, and Maria Sarah Turner. From age seven, Hooker attended his father’s lectures at Glasgow University, taking an early interest in plant distribution and the voyages of explorers like Captain James Cook. He was educated at the Glasgow High School and went on to study medicine at Glasgow University, graduating M.D. in 1839. This degree qualified him for employment in the Naval Medical Service and he joined the renowned polar explorer Captain James Clark Ross’s Antarctic expedition to the South Magnetic Pole after receiving a commission as Assistant-Surgeon on HMS Erebus.

The Expedition of James Clark Ross to the Antarctic

The expedition led by James Clark Ross was the last major voyage of exploration made entirely under sail. Hooker was the youngest crew member as assistant to Robert McCormick, who in addition to being the ship’s Surgeon was instructed to collect zoological and geological specimens. The ships sailed on 30 September 1839 towards Antarctica they and visited Madeira, Tenerife, Santiago and Quail Island in the Cape Verde archipelago, St Paul Rocks, Trinidade east of Brazil, St Helena, and the Cape of Good Hope. Hooker made plant collections at each location and while travelling drew these and specimens of algae and sea life pulled aboard using tow nets. The expedition spent some time in Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land, and then moved on to the Auckland Islands and Campbell Island, and onward to Antarctica to locate the South Magnetic Pole.

After spending 5 months in the Antarctic they returned to resupply in Hobart, then went on to Sydney, and the Bay of Islands in New Zealand. They left New Zealand to return to Antarctica. After spending 138 days at sea, and a collision between the Erebus and Terror, they sailed to the Falkland Islands, to Tierra del Fuego, back to the Falklands and onward to their third sortie into the Antarctic. They made a landing at Cockburn Island and after leaving the Antarctic, stopped at the Cape, St Helena and Ascension Island. The ships arrived back in England on 4 September 1843. Hooker’s collections from the Antarctic voyage were described eventually in one of two volumes published as the Flora Antarctica (1844–47).

University Career

In 1845, Hooker applied for the Chair of Botany at the University of Edinburgh. An unusually protracted struggle ensued, resulting in the election of the locally born and bred botanist, John Hutton Balfour. Hooker declined a chair at Glasgow University which became vacant on Balfour’s appointment. Instead, he took a position as botanist to the Geological Survey of Great Britain in 1846. He began work on palaeobotany, searching for fossil plants in the coal-beds of Wales, eventually discovering the first coal ball in 1855.

Travels to India

In 1847 his father nominated him to travel to India and collect plants for Kew being the first European to collect plants in the Himalaya. With a Treasury grant and a commission in the Royal Navy, he spent three years in northeast India, mainly in the Himalayan state of Sikkim and in eastern Nepal, engaged in botanical exploration and topographical surveying. Hooker was practically the first explorer of the eastern Himalaya since Turner’s embassy to Tibet in 1789. Not only did he add much to the existing knowledge of the Indian flora but he also made detailed meteorological and geological observations, while his accurate survey work on the complex mountain terrain formed the basis of a map published by the India Trigonometrical Survey. Horticulturalists will always associate Hooker’s name with the genus Rhododendron because he introduced a number of new species into cultivation in England and published his findings in Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya in 1849. During his researches on the Indian flora, Hooker became aware of the need for a taxonomic revision of the genus Impatiens. His last years were occupied with an intensive investigation of this genus, of which he described more than 300 species as being new.[3]

When Hooker met Darwin

“From my earliest childhood I nourished and cherished the desire to make a creditable journey in a new country, and write such a respectable account of its natural history as should give me a niche amongst the scientific explorers of the globe I inhabit, and hand my name down as a useful contributor of original matter.”

— Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, Letter to Charles Darwin (1854)

Hooker met Darwin briefly for the first time in 1839 and within a few years they had become close friends. While on the Erebus, Hooker had read proofs of Charles Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle provided by Charles Lyell and had been very impressed by Darwin’s skill as a naturalist.[5] After Hooker’s return to England, he was approached by Darwin who invited him to classify the plants that Darwin had collected in South America and the Galápagos Islands. Their correspondence continued throughout the development of Darwin’s theory and in 1858 Darwin wrote that Hooker was “the one living soul from whom I have constantly received sympathy“. At the historic debate on evolution held at the Oxford University Museum on 30 June 1860, Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, Benjamin Brodie and Robert FitzRoy spoke against Darwin’s theory, and Hooker and Thomas Henry Huxley defended it. According to Hooker’s own account, it was he and not Huxley who delivered the most effective reply to Wilberforce’s arguments.

Later Years

By his travels and his publications, Hooker built up a high scientific reputation at home. In 1855 he was appointed Assistant-Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and in 1865 he succeeded his father as full Director, holding the post for twenty years. Under the directorship of father and son Hooker, the Royal Botanic gardens of Kew rose to world renown. At the age of thirty, Hooker was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1873 he was chosen its president (till 1877). He received three of its medals: the Royal Medal in 1854, the Copley in 1887 and the Darwin Medal in 1892. He was the author of numerous scientific papers and monographs, and his larger books included, in addition to those already mentioned, a standard Students Flora of the British Isles and a monumental work, the Genera plantarum (1860–83), based on the collections at Kew, in which he had the assistance of George Bentham. In 1904, at the age of 87, Hooker published A sketch of the Vegetation of the Indian Empire.

Joseph Dalton Hooker died on 10 December 1911, at age 94.

Bentham and Hooker Classification, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] James Clark Ross and the Ross Expedition, SciHi Blog, February 2, 2017.

- [2] Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, British Botanist, at Britannica Online

- [3] “Hooker, Joseph Dalton.” Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. . Encyclopedia.com.

- [4] Charles Darwin’s ‘On the Origin of Species’, SciHi Blog, November 24, 2012.

- [5] Charles Lyell and the Principles of Geology, SciHi Blog

- [6] Joseph Dalton Hooker at Wikidata

- [7] “Correspondence between Joseph Hooker and Charles Darwin”. Darwin Correspondence Project. University of Cambridge. 1843–1882.

- [8] Works by or about Joseph Dalton Hooker at Internet Archive

- [9] Directors’ Correspondence Project – Correspondence to Joseph Dalton Hooker as Director of The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

- [10] Bentham and Hooker Classification, Vivek Roy’s Plant Biology @ youtube

- [11] Timeline of English Botanists, via DBpedia and Wikidata