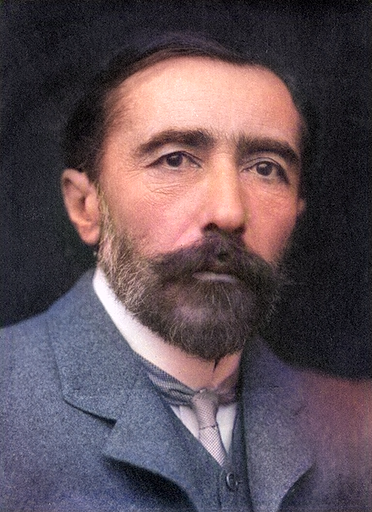

Joseph Conrad (1857-1924)

On December 3, 1857, Polish-British writer Joseph Conrad was born. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists to write in the English language. Though he did not speak English fluently until his twenties, he was a master prose stylist who brought a non-English sensibility into English literature.

“A work that aspires, however humbly, to the condition of art should carry its justification in every line. And art itself may be defined as a single-minded attempt to render the highest kind of justice to the visible universe, by bringing to light the truth, manifold and one, underlying its every aspect. It is an attempt to find in its forms, in its colors, in its light, in its shadows, in the aspects of matter and in the facts of life what of each is fundamental, what is enduring and essential—their one illuminating and convincing quality — the very truth of their existence.”

— Joseph Conrad, The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ (1897)

Family Background and Early Years

Joseph Conrad was born in Berdyczów in the governorate of Kiev (today Ukraine) as the son of Polish parents, both of whom came from noble families and belonged to the Coat of Arms Community Nałęcz. Conrad’s father, Apollo Korzeniowski, was a writer and Polish patriot who translated William Shakespeare and Victor Hugo into Polish. He encouraged his son to read Polish and French literature. His father was arrested in 1861 for his commitment to regaining Polish independence and was banished nine months later to Vologda in northern Russia, where his wife Ewelina (née Bobrowska) and his son accompanied him. Conrad’s mother died there in 1865. After his release from exile, his father went to the Polish-speaking part of Austria and lived for a short time in Krakow, where Conrad attended grammar school, where he died in 1869.

His uncle Tadeusz Bobrowski received custody of the eleven-year-old child. In 1874 he allowed the sixteen-year-old teenager to go to Marseille in France to become a sailor. In 1878 Conrad set foot on British soil for the first time. In 1886 he received British citizenship at the age of 30. In 1888 he became captain of the Otago; it was to be his only position as captain. His experiences at sea, especially in the Congo and on the Malay islands, form the background of his work.

How the River Captain became a Novelist

He began his career as a writer around 1890. As captain of a river steamer at the Stanley Falls of the Congo, he had developed a severe fever (like most Europeans) and had to be brought ashore in a canoe. The canoe capsized, but Conrad was rescued. At that time he had the opening chapters of his first novel with him. The fever never left him again, a last attempt to recover at sea in 1893 failed.

Conrad wrote in English, which he had only begun to learn at the age of 21. In 1895 he published his first novel Almayer’s Folly: A story of an Eastern River. The author he would like to be is supposed to be a Briton and English the language of his literary self – a foreign language that Conrad first was less familiar with than Polish or French. It should become the mirror of his new identity, in which his past became unrecognisable, and the material of his narrative self-definition. Now that Conrad was earnestly writing, he had numerous works first serialised in such publications as Blackwood’s, Munsey’s and Harper’s. Other works published around this time include An Outcast of the Islands (1896), The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ (1897), Tales of Unrest (1898), Lord Jim (1900), in collaboration with Ford Madox Ford The Inheritors (1901) and Romance (1903), Youth (1902), The End of the Tether (1902), Typhoon (1903), Nostromo (1904), The Mirror of the Sea (1906, semi-autobiographical), The Secret Agent (1907, dedicated to H.G. Wells), A Set of Six (1908), and Under Western Eyes (1911).

Literary Breakthrough

For a long time he was dependent on patrons. It was not until 1914 that he had his literary breakthrough with Chance. His novels and stories are among the most important works of English literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The fact that Conrad’s life and texts are marked by the cultural conflicts and mix-ups of the colonial age has further increased the interest in this author in the course of the postcolonialist turn in cultural studies. While Joseph Conrad was admired by modernist authors such as André Gide, Thomas Mann, Jorge Luis Borges, and Philip Roth for his sophisticated literary narrative techniques, he is now at the center of interest as the author of highly ambivalent depictions of colonial violence. His most famous novella ‘Heart of Darkness‘ (1902) vividly reveals the horror and cruelty of colonialism; at the same time, racist stereotypes permeate his works.

The Heart of Darkness

“I saw on that ivory face the expression of somber pride, of ruthless power, of craven terror — of an intense and hopeless despair. Did he live his life again in every detail of desire, temptation, and surrender during that supreme moment of complete knowledge? He cried in a whisper at some image, at some vision, — he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath — ‘The horror! The horror!’

— Joseph Conrad, The Heart of Darkness, Part III (1899)

The Heart of Darkness was originally serialized in three parts in Blackwood’s Magazine (1899). It is a novel about a narrated voyage up the Congo River into the Congo Free State in the so-called heart of Africa. Charles Marlow, the narrator, tells his story to friends aboard a boat anchored on the River Thames. This setting provides the frame for Marlow’s story of his obsession with the Belgian ivory trader Kurtz, who apparently has gone insane, which enables Conrad to create a parallel between what Conrad calls “the greatest town on earth“, London, and Africa as places of darkness. Central to Conrad’s work is the idea that there is little difference between so-called civilised people and those described as savages; Heart of Darkness raises questions about imperialism and racism. The centre of Heart of Darkness is the figure of Kurtz. As head of the outpost of the trading company, he embodies the perfidious, unscrupulous colonialist. Through unrestrained exploitation of the locals, he exceeds his task in pathological ambition even in the eyes of his superiors. The Darwinian component of racial superiority is expressed in Kurtz’s report on the suppression of the primitive customs of the natives, which Marlow reads in the Congo.

Orson Welles had already considered filming the material in 1940, but then rejected the plan.[7] The best known version of the material is that by Francis Ford Coppola from 1979, who transported the story into the Vietnam War and brought it into the cinemas as an anti-war film with a large cast of stars (Marlon Brando, Martin Sheen, Robert Duvall, Dennis Hopper, Laurence Fishburne and Harrison Ford): Apocalypse Now.

Later Life

More than the sea, the Malay island landscape and the African continent, identity and transformation are the central motifs of Conrad’s life and writing. In Lord Jim, the main character has prematurely left a sinking refugee ship, committing a crime that not only contradicts his ethos, but is incompatible with his self. This unacceptable past becomes the driving force behind his escape into another life.

Around 1920 Joseph Conrad had become a radiant public figure. However, his high income did not prevent him from getting into financial difficulties again and again through even higher expenses for his family and the luxuriant staff (cooks, gardeners, private instructors and chauffeurs) on his dearly rented house ‘Oswald’s’, from which friends or his agent Pinker helped him out. He now received a large number of honorary doctorates and invitations to read. Admittedly, he usually rejected them, not least because of an astonishing insecurity in spoken English for this master of languages, which remained afflicted with a strong accent throughout his life.

Interestingly, Conrad despised Fyodor Dostoevsky,[8] another Slavic writer and master of psychology often cited as marking the transition between realist and modern fiction. Conrad also despised Russian writers as a rule, due to his parents’ deaths at the hands of the Russian authorities, making an exception only for Ivan Turgenev. Although Conrad deploys some of the modernist techniques (most notably, the interior monologue), unlike modernists such as James Joyce, Marcel Proust, or the late Henry James, he still retains forms of a standard, realistic narrative. Nevertheless, his works, like those of other modernists, possess a symbolic resonance and layers of meaning that go beyond the level of the plot.[5]

On August 3, 1924 Conrad died of heart failure in the house ‘Oswalds’ in Bishopsbourne, Kent, where he had lived with his family since 1919. He is buried with his wife Jessie in the cemetery of Canterbury. On his gravestone are the lines of Edmund Spenser, which precede Conrad’s penultimate novel The Privateer:

“Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas, Ease after warre, death after life, does greatly please.”

Rob Crawford, Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Orson Welles’ Disputed Masterpiece Citizen Kane, SciHi Blog

- [2] The Joseph Conrad Society

- [3] Joseph Conrad at IMBD

- [4] Works of and about Joseph Conrad, at Wikisource

- [5] Joseph Conrad at The New World Encyclopaedia

- [6] Leo Robson, Joseph Conrad’s Journey, Was the novelist right to think everyone was getting him wrong?, in The New Yorker, November 20, 2017 Issue

- [7] Orson Welles and the 1938 Radio Show Panic, SciHi Blog

- [8] Fyodor Dostoyevsky – Crime and Punishment, SciHi Blog

- [9] Joseph Conrad at Wikidata

- [10] Rob Crawford, Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness, UBC Arts One @ youtube

- [11] Sherry, Norman, ed. (1973). Conrad: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- [12] Curle, Richard (1914). Joseph Conrad. A Study. Doubleday, Page & Company.

- [13] Wise, T.J. (1920) A Bibliography of the Writings of Joseph Conrad (1895–1920). London: Printed for Private Circulation Only By Richard Clay & Sons, Ltd.

- [14] Morton Dauwen Zabel, “Conrad, Joseph”, Encyclopedia Americana, 1986 ed., vol. 7, pp. 606–07.

- [15] Timeline for Joseph Conrad, via Wikidata