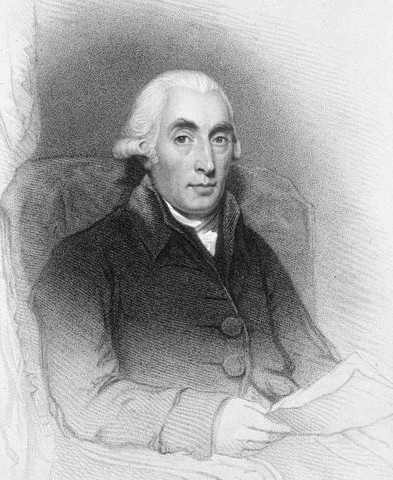

Joseph Black (1728-1799)

On April 16, 1742, Scottish physician and chemist Joseph Black was born. He is best known for his discoveries of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide.

“As the ostensible effect of the heat … consists not in warming the surrounding bodies but in rendering the ice fluid, so, in the case of boiling, the heat absorbed does not warm surrounding bodies but converts the water into vapor. In both cases, considered as the cause of warmth, we do not perceive its presence: it is concealed, or latent, and I gave it the name of “latent heat.”

— Joseph Black (1728-1799)

Joseph Black – Early Years

Joseph Black was the son of an Irish-born wine merchant, John Black, who lived in Scotland and later in Bordeaux. The large family had contact with Montesquieu in France. At the age of 12, Black was sent to his home in Belfast to learn Latin and Greek, and subsequently, aged 16, enrolled at Glasgow University in 1744 to study arts. After y few years however, his father managed to persuade him of choosing a more useful profession and so he started medicine. The professor of medicine in Glasgow at this time was William Cullen who had instituted the first lectures in Chemistry in 1747. Black wrote later: “Dr Cullen about this time began also to give lectures in chemistry which had never been taught in the University of Glasgow and finding that I might be useful to him in that Undertaking he employed me as his assistant in the laboratory“. In 1756, Joseph Black was appointed Professor of Anatomy and Botany, and Lecturer in Chemistry in Glasgow. About ten years later, he succeeded Cullen to the chemistry and medicine chairs in Edinburgh. In 1783, Joseph Black was also one of the founders of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

The Discovery of Carbon Dioxide

In Black’s early years at Glasgow, he probably started his work on the chemistry of “magnesia alba“. He submitted his work later for his MD thesis in Edinburgh including the discovery of what we now call carbon dioxide, Joseph Black called it “fixed air“. Black observed that the fixed air was denser than air and did not support either flame or animal life. Black also found that when bubbled through an aqueous solution of lime (calcium hydroxide), it would precipitate calcium carbonate. He used this phenomenon to illustrate that carbon dioxide is produced by animal respiration and microbial fermentation. These works foreshadowed Lavoisier’s work, and highly contributed to the foundations for modern chemistry.[4,5]

The Measurement of Heat

After meeting James Watt around 1756, it is assumed that Joseph Black was stimulated in his work involving the concept of latent heat, and the first steps in calorimetry. He proceeded to measure heat carefully, “He waited with impatience for the winter” in Glasgow in order to perform experiments on the freezing and melting of water and water/alcohol mixtures that led to the concept of latent heat of fusion. Black also used similar work establishing the idea of latent heats of vaporization, leading to the general concept of heat capacity or specific heat. These early steps in thermodynamics went on alongside James Watt’s developments of improved steam engines.[6] It is believed that Watt and Joseph Black became friends and Black is even supposed to have provided significant financing and other support for Watt’s early research in steam power.

Heat Capacity

Black also studied the temperature change of water using a thermometer. When heat was applied to a water vessel, the mercury scale of the thermometer expanded, whereas with ice, the application of heat showed no change in temperature for a long time. The temperature of the thermometer also did not change when water vapour was formed. Black concluded that during boiling and melting, heat was still supplied although the temperature did not change. Black recognized that a distinction had to be made between the intensity (temperature) and the amount of heat (quantity). Black also found that different substances could also absorb different amounts of heat.

Later Years

Black’s research and teaching were reduced as a result of poor health. From 1793 his health declined further and he gradually withdrew from his teaching duties. In 1795, Charles Hope was appointed his coadjutor in his professorship, and in 1797 he lectured for the last time. Black never married. He died peacefully at his home in Edinburgh in 1799 at the age of 71.

Jim Butler, The History of Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Joseph Black at the University of Glasgow

- [2] Ramsay, William (1918). The Life and Letters of Joseph Black. London: Constable

- [3] Eklund JB, Davis AB (October 1972). “Joseph Black matriculates: medicine and magnesia alba“. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences

- [4] Modern Chemistry started with Lavoisier, SciHi Blog

- [5] Antoine Lavoisier’s Theory of Combustion, SciHi Blog

- [6] James Watt and the Steam Age Revolution, SciHi Blog

- [7] Joseph Black at Wikidata

- [8] Joseph Black at Reasonator

- [9] Guerlac, Henry (1970–1980). “Black, Joseph”. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 173–183.

- [10] . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- [11] Works by or about Joseph Black at Internet Archive

- [12] Jim Butler, The History of Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide, Exploratorium @ youtube

- [13] Eddy, Matthew Daniel. “Useful Pictures: Joseph Black and the Graphic Culture of Experimentation”. In Robert G. W. Anderson (Ed.), Cradle of Chemistry: The Early Years of Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2015), 99-118.

- [14] Ramsay, William (1918). The Life and Letters of Joseph Black. London: Constable

- [15] Timeline of Thermodynamicists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #14 | Whewell's Ghost