John Tyndall (1820-1893)

caricatured as a preacher

in the magazine Vanity Fair, 1872

On August 2, 1820, British physicist John Tyndall was born. His initial scientific fame arose in the 1850s from his study of diamagnetism. Later he made discoveries in the realms of infrared radiation and the physical properties of air. As the most prominent example, he was able to demonstrate why the sky is blue.

“Every occurrence in Nature is preceded by other occurrences which are its causes, and succeeded by others which are its effects. The human mind is not satisfied with observing and studying any natural occurrence alone, but takes pleasure in connecting every natural fact with what has gone before it, and with what is to come after it.”

— John Tyndall [7]

John Tyndall – Early Years

John Tyndall was born in Leighlinbridge, County Carlow, Ireland, where his father was a local police constable. He attended the local schools in County Carlow until his late teens, and was probably an assistant teacher near the end of his time there. Subjects learned at school notably included technical drawing and mathematics with some applications of those subjects to land surveying. In 1839, he was hired as a draftsman by the government’s land surveying mapping agency in Ireland and England. In the decade of the 1840s, a railroad-building boom was in progress, and Tyndall’s land surveying experience was valuable and in demand by the railway companies, who employed Tyndall in railway construction planning.

Academic Career

In 1847 he began to teach mathematics at Queenwood College Hampshire. He began his scientific career with Friedrich Stegmann in Marburg with studies in the field of diamond magnetism and magneto-optical properties of crystals. He was one of the first British subjects to receive the new Ph.D. at Marburg. Tyndall stayed even longer in Germany and went for one year to Gustav Magnus [6] at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-University Berlin doing research on magnetism. His years in Germany while still a young man turned Tyndall into something of a naturphilosophisch romantic pantheist [1]. In summer 1851, Tyndall returned to England, where he first continued his experimental work on magnetism and diamagnetic polarity, which soon made Tyndall known among the leading scientists of the day. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1852. In 1853, he attained the prestigious appointment of Professor of Natural Philosophy (Physics) at the Royal Institution in London, due in no small part to the esteem his work had garnered from Michael Faraday,[5] the leader of magnetic investigations at the Royal Institution, whose successor be became at the Royal Institution after Faraday’s retirement.

Heat Absorption and Transmission of Gases

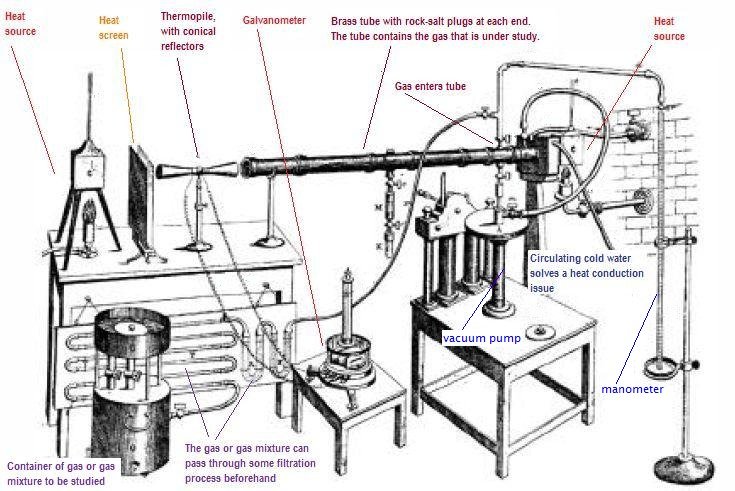

In 1859 Tyndall began to study the capacities of various gases to absorb or transmit radiant heat. He showed that the main atmospheric gases, nitrogen and oxygen, are almost transparent to radiant heat, whereas water vapour, carbon dioxide and ozone are such good absorbers that, even in small quantities, these gases absorb heat radiation much more strongly than the rest of the atmosphere. Tyndall concluded that water vapour is the strongest absorber of heat in the atmosphere and is the principal gas controlling surface air temperature by inhibiting leakage of the Earth’s heat back into outer space. He declared that, without water vapour, the Earth’s surface would be ‘held fast in the iron grip of frost’ – the greenhouse effect.

Tyndall’s setup for measuring the radiant heat absorption of gases.

Blue Skies and the Tyndall Effect

In 1869 Tyndall discovered the scattering of light by dust and large molecules, now known as the Tyndall Effect. He noticed that a beam of light, visible as it passed through ordinary laboratory air, disappeared when it entered a flask of pure filtered water. He now passed a light beam through filtered air and got the same result – no beam. He deduced that light bounces off little particles and into our eyes, allowing us to see the beam. He found that different sized particles scattered light in different ways. Tyndall suggested that the sky is blue because molecules in the atmosphere preferentially scatter the sun’s blue rays. [3]

Glacier Research and Mountaineering

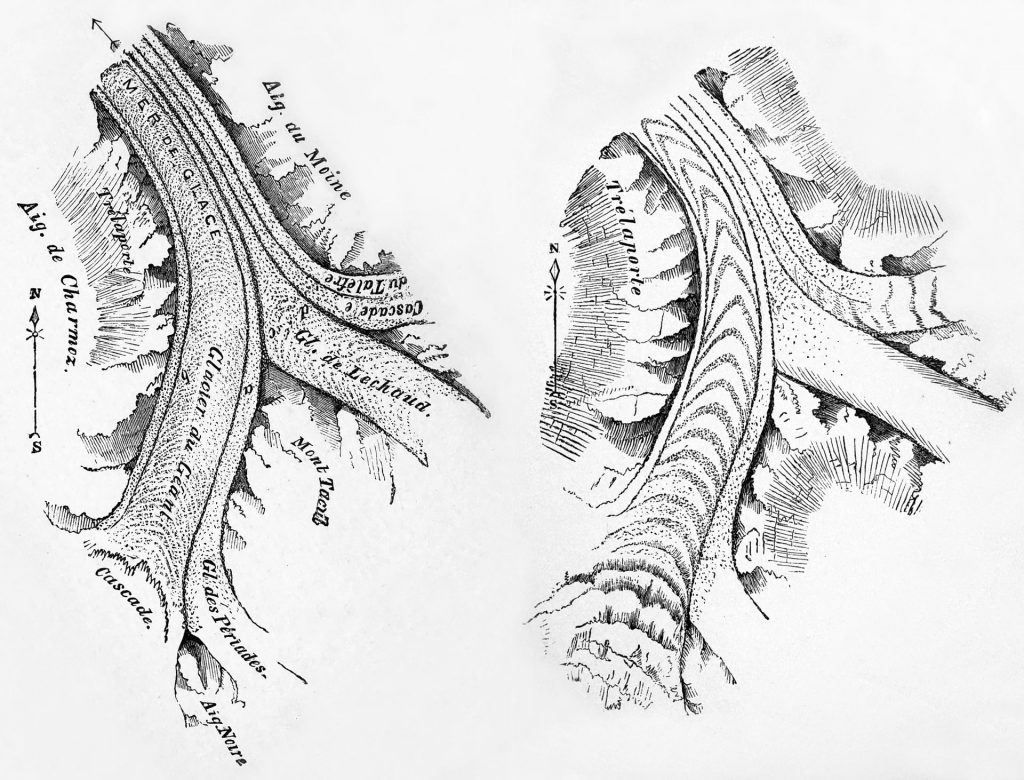

John Tyndall combined his glacier researches with mountaineering, at which he became expert. On August 19, 1861, Tyndall, together with the mountain guides Johann Josef Benet and Ulrich Wenger von Randa, succeeded in the first ascent of the Weisshorn. He climbed Mount Blanc, the highest alpine peak, several times. He narrowly missed being the first person to summit the Matterhorn (he was third), and made numerous other difficult climbs throughout the Alps. Mountaineering gained the status of a sport partly because of his popular narratives, including his Glaciers of the Alps (1860) and Hours of Exercise in the Alps (1871) [2]. In January 1859 he noted the winter advance of the Mer de Glace. In his search for the causes of the past ice ages, he was not only the first to discuss a change in the concentration of the greenhouse gases water vapour and carbon dioxide, but also to make concrete measurements that enabled him to identify the gases responsible for the natural greenhouse effect.

John Tyndall explored the glacial tributaries feeding Mer de Glace in 1857. General topology (left); dirt-bands in glacier (right).

Later Years

“Knowledge once gained casts a faint light beyond its own immediate boundaries.”

– John Tyndall [9]

Tyndall made many other contributions to science. For example he invented the fireman’s respirator and his invention of the light pipe led to the development of fibre optics. In 1859, he was elected a corresponding member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences. Tyndall married Louisa Hamilton at the age of 56. Insomnia plagued Tyndall, and this, combined with general ill-health, led to his resignation from the Royal Institution in 1887. As his insomnia got worse he experimented with a variety of drugs. He died in 1893 from an accidental overdose of chloral administered by Louisa.

Mehran Kardar, 7. Kinetic Theory of Gases Part 1, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] John Tyndall at the Victorian Web

- [2] About Tyndall, at York University, CA

- [3] John Tyndall at Understanding Science

- [4] John Tyndall at The Royal Institution

- [5] A Life of Discoveries – the great Michael Faraday , SciHi blog

- [6] Heinrich Gustav Magnus and the Magnus Effect, SciHi Blog

- [7] John Tyndall, Forms of Water in Clouds and Rivers, Ice and Glaciers (1872)

- [8] Works by or about John Tyndall at Internet Archive

- [9] John Tyndall, On the Methods and Tendencies of Physical Investigation, Scientific Addresses (1870)

- [10] John Tyndall at Wikidata

- [11] Mehran Kardar, 7. Kinetic Theory of Gases Part 1, MIT OpenCourseWare @ youtube

- [12] DeYoung, Ursula (2011). A Vision of Modern Science: John Tyndall and the Role of the Scientist in Victorian Culture. Palgrave Macmillan.

- [13] Timeline of Atmospheric Physicists, via Wikidata and DBpedia