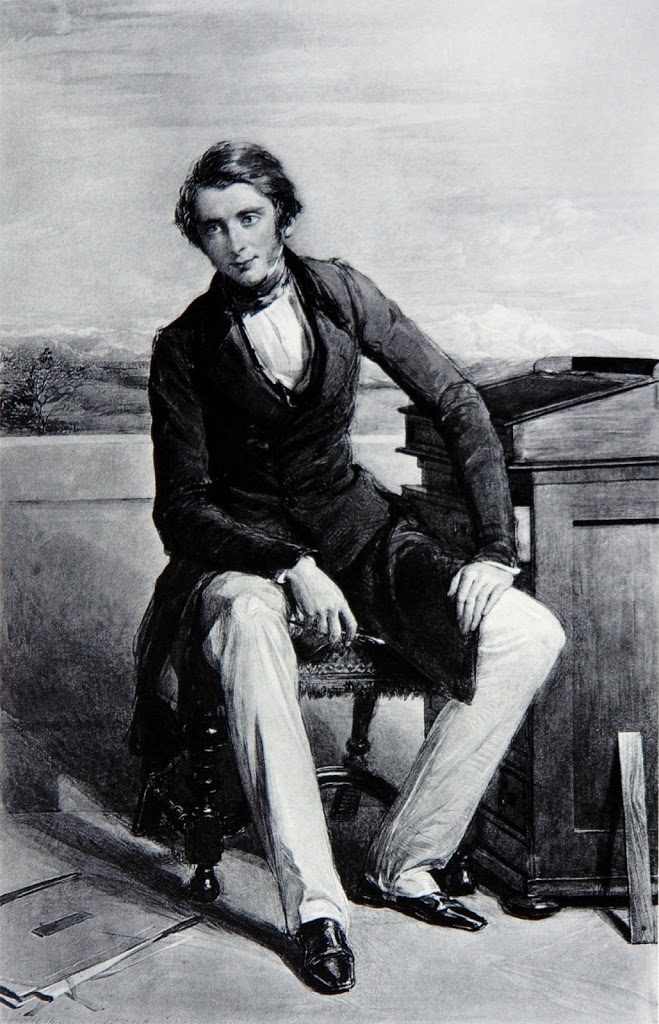

John Ruskin (1819-1900)

On February 8, 1819, prominent social thinker and philanthropist John James Ruskin was born. He is considered the leading English art critic of the Victorian era, also an art patron, draughtsman and watercolourist. He was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century up to the First World War and today, his ideas and concerns are widely recognised as having anticipated interest in environmentalism, sustainability and craft.

“No small misery is caused by overworked and unhappy people, in the dark views which they necessarily take up themselves, and force upon others, of work itself.”

— John Ruskin, Pre-Raphaelitism, section 1 (1851)

Ruskin’s Family Background

Ruskin grew up in London, being home schooled and traveling with his parents through Europe extensively throughout his childhood. His father, John James Ruskin, , was a sherry and wine importer. Ruskin’s interest in poetry grew early and was emphasized by his father’s support, who encouraged him to publish his first poem at the age of 11. Ruskin later attended the University of Oxford, Christ Church, continuing to publish further poems and criticism successfully. Enrolled as a gentleman-commoner, he enjoyed equal status with his aristocratic peers. There, he became close to the geologist and natural theologian, William Buckland.[5] Among Ruskin’s fellow undergraduates, the most important friends were Charles Thomas Newton and Henry Acland.

Father’s Debts and First Publications

However, Ruskin had hoped to practice law, and was articled as a clerk in London. Unfortunately, his father was an incompetent businessman. To save the family from bankruptcy, John James, whose prudence and success were in stark contrast to his father, took on all debts, settling the last of them in 1832. From September 1837 to December 1838, Ruskin’s The Poetry of Architecture was serialised in Loudon’s Architectural Magazine, under the pen name “Kata Physin” (Greek for “According to Nature“). It was a study of cottages, villas, and other dwellings which centred on a Wordsworthian argument that buildings should be sympathetic to their immediate environment and use local materials, and anticipated key themes in his later writings.[1] In 1839, Ruskin’s ‘Remarks on the Present State of Meteorological Science‘ was published in Transactions of the Meteorological Society.

Newdigate Prize and Graduation

His biggest success came in 1839 when at the third attempt he won the prestigious Newdigate Prize for poetry. His health was poor and he was devastated to hear his first love, Adèle Domecq, second daughter of his father’s business partner, was engaged to a French nobleman. In the midst of exam revision, in April 1840, he coughed blood, raising fears of consumption, and leading to a long break from Oxford. At Oxford, he sat for a pass degree in 1842, and was awarded with an uncommon honorary double fourth-class degree in recognition of his achievements.

The Paintings of J. M. W. Turner

“The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and tell what it saw in a plain way. Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands can think for one who can see. To see clearly is poetry, prophecy, and religion, — all in one.”

— John Ruskin, Modern Painters (1843-1860)

Ruskin was galvanized into writing a defence of J. M. W. Turner [6] when he read an attack on several of Turner’s pictures exhibited at the Royal Academy. It recalled an attack by critic, Rev John Eagles, in Blackwood’s Magazine in 1836, which had prompted Ruskin to write a long essay. John James had sent the piece to Turner who did not wish it to be published. It finally appeared in 1903. In the time between 1842 and 1846, two volumes of ‘Modern Painters‘ concerning theories of beauty and imagination in landscape and figural painting were published. What became the first volume of Modern Painters was Ruskin’s response to Turner’s critics. Ruskin controversially argued that modern landscape painters – and in particular Turner – were superior to the so-called “Old Masters” of the post-Renaissance period. Ruskin maintained that Old Masters such as Gaspard Dughet, Claude, and Salvator Rosa, unlike Turner, favored pictorial convention, and not “truth to nature“. He explained that he meant “moral as well as material truth“. The job of the artist is to observe the reality of nature and not to invent it in a studio – to render what he has seen and understood imaginatively on canvas, free of any rules of composition.

The Beautiful as a Gift of God

Drawing on his travels, he wrote the second volume of Modern Painters (published April 1846). This volume concentrated more on Renaissance and pre-Renaissance artists than on Turner. It was a more theoretical work than its predecessor. Ruskin explicitly linked the aesthetic and the divine, arguing that truth, beauty and religion are inextricably bound together: “the Beautiful as a gift of God“. In defining categories of beauty and imagination, Ruskin argued all great artists must perceive beauty and, with their imagination, communicate it creatively through symbols

Writing, Traveling, and Marriage

In the following years, John Ruskin got married and published several works, like his only piece of prose, the fairy tale ‘The King of the Golden River‘ in 1850. He then got separated from his wife and began teaching at the Working Men’s College. The next years were Ruskin’s most productive. ‘The Academy Notes‘, further volumes of ‘Modern Painters, or ‘The Political Economy of Art‘ were published next to further projects with his close friend Charles Eliot Norton. The last years of his life, Ruskin spent rather busy with writing and traveling, but his health problems began to increase at 1880, when re resigned from his teaching position. One of his last works was ‘Praeterita‘, his autobiography and he passed away in January 1900.

Ruskinian Gothic

John Ruskin wrote over 250 works considering history, criticism, art, but also geology or literature. Ruskin was also a great fan of Gothic, inspiring artists of his time to reproduce Gothic art, due to its appreciation of nature and all of its forms. According to Ruskin, Gothic architecture is characterized by natural and moral truths and human emotions in contrast to classical architecture. This led to the publication of The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849). It contained 14 plates etched by the author. The title refers to seven moral categories that Ruskin considered vital to and inseparable from all architecture: sacrifice, truth, power, beauty, life, memory and obedience. Ruskin’s theories also inspired some architects to adapt the Gothic style. Such buildings created what has been called a distinctive “Ruskinian Gothic“

The Stones of Venice

Due to his high engagement in architecture and the preference of Gothic architecture, ‘The Stones of Venice‘ gained of great importance among Ruskins works in which he summarized all of his arguments. Developing from a technical history of Venetian architecture, from the Romanesque to the Renaissance, into a broad cultural history, Stones also reflected Ruskin’s view of contemporary England. It acted as a warning about the moral and spiritual health of society. Ruskin argued that Venice had slowly deteriorated. Its cultural achievements had been compromised, and its society corrupted, by the decline of true Christian faith. Ruskin detested restoration of buildings due to his opinion, that “it is impossible, as impossible as to raise the dead, to restore anything that has ever been great or beautiful in architecture“.

Further Occupations

Besides architecture, Ruskin loved painting and sketching himself since his early childhood, especially landscapes, buildings or animals and due to his detailed study of nature, he was able to create distinctive art, seen in various exhibitions at his time. He was also an enthusiastic art collector and art-philanthropist, giving away numerous paintings to English museums.

The Political Economy of Art

In ‘The Political Economy of Art‘, Ruskin made his contempt considering orthodox clear and encouraged society to understand the political and economic complexity, as well as to respect the worker’s role in society, attacking Adam Smith’s theories in ‘The Wealth of Nations‘ and the theory of the division of labor, causing dissatisfaction among craftsmen and workers. In ‘Unto This Last‘ from 1862, Ruskin explained several arguments concerning social justice promoting education in every sense of living, helping young people find a decent employment, which set first basics for the welfare state theories.

Later Years

“The secret of language is the secret of sympathy and its full charm is possible only to the gentle.”

— John Ruskin, Lectures in Art (1870)

Ruskin was unanimously appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University in August 1869. In 1871, John Ruskin founded his own art school at Oxford, The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. In 1879, Ruskin resigned from Oxford, but resumed his Professorship in 1883, resigning again in 1884. John Ruskin died on January 20, 1900, aged 80.

Geoffrey Tyack, Ruskin Lecture 2021: John Ruskin: Art, Architecture and the Natural World, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] William Wordsworth and the Romantic Age of English Literature, SciHi Blog, April 7, 2014.

- [2] Ruskin at the Victorian Web

- [3] The Ruskin Society

- [4] Ruskin at BBC

- [5] William Buckland and the Dinosaurs, SciHi Blog, March 12, 2013.

- [6] William Turner – Romantic Preface to Impressionism, SciHi Blog, April 23, 2016.

- [7] John Ruskin at Wikidata

- [8] Geoffrey Tyack, Ruskin Lecture 2021: John Ruskin: Art, Architecture and the Natural World, Kellogg College, University of Oxford @ youtube

- [9] Cook, E. T. Ruskin, John. Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1901.

- [10] Waldstein, C. The Work of John Ruskin: Its Influence Upon Modern Thought and Life, Harper’s magazine vol. 78, no. 465 (Feb. 1889), pp. 382–418.

- [11] Timeline for Jon Ruskin, via Wikidata