Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814)

On May 19, 1762, German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte was born. Fichte was one of the founding figures of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kant. Thus, Fichte often is regarded as a bridging figure between Immanuel Kant and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Like Descartes and Kant before him, he was motivated by the problem of subjectivity and consciousness. Maybe you have never heard of Fichte. It was also only recently that philosophers and scholars have begun to appreciate Fichte as an important philosopher in his own right due to his original insights into the nature of self-consciousness or self-awareness.

“Upon the progress of knowledge the whole progress of the human race is immediately dependent: he who retards that, hinders this also.”

— Johann Gottlieb Fichte, The Vocation of the Scholar (1794)

Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s Way to Kant

Fichte was born on May 17, 1762, in Rammenau, Upper Lusatia as the son of Christian Fichte, a ribbon weaver. The Fichte family was noted in the neighborhood for its probity and piety. There is the story that Fichte owes the chance of a good education his profound memory. One day, the Freiherr von Militz, a country landowner, arrived too late to hear the local pastor preach. He was, however, informed that a lad in the neighborhood would be able to repeat the sermon practically verbatim. As a result the baron took the lad, who was young Fichte, into his protection, which meant that he paid his tuition. After having visited the the celebrated foundation-school at Pforta near Naumburg, where also the brothers August Wilhelm and Friedrich Schlegel as well as Friedrich Nietzsche had spent their school days, Fichte began study at the Jena theology seminary in 1780. Unfortunately, his patron Freiherr von Militz died in 1784 and Fichte had to end his studies prematurely, without completing his degree. For the next years, he worked as a private tutor and in 1790 finally, Fichte began to study the works of Immanuel Kant, but this occurred initially only because one of his students wanted to know about them. However, they had a lasting effect on his life as well as on his thought.

Attempt at a Critique of All Revelation

In 1791, Fichte had the chance to see Kant at Königsberg. But the interview was rather dissapointing. He shut himself in his lodgings and threw all his energies into the composition of an essay to raise Kant’s attention and interest. The Versuch einer Kritik aller Offenbarung (Attempt at a Critique of All Revelation, 1792) was written in five weeks only. There, Fichte investigated the connections between divine revelation and Kant’s critical philosophy. The first edition of the book was published without Fichte’s name and signed preface. Therefore, it was thus mistakenly credited to be a new work by Kant himself. When Kant cleared the confusion and openly praised the work and author, Fichte’s reputation skyrocketed. Now, the French revolution was creating excitement all over Europe. Inspired by its principles Fichte wrote and published anonymously two pamphlets which led to him being seen as a devoted defender of liberty of thought and action and an advocate of political changes. The same year, he received an invitation to fill the position of extraordinary professor of philosophy at the University of Jena, which he gladly accepted. With extraordinary zeal, he expounded his system of “transcendental idealism.” His success was immediate.

“Humanity may endure the loss of everything: all its possessions may be torn away without infringing its true dignity; — all but the possibility of improvement.”

— Johann Gottlieb Fichte, The Vocation of the Scholar” (1794)

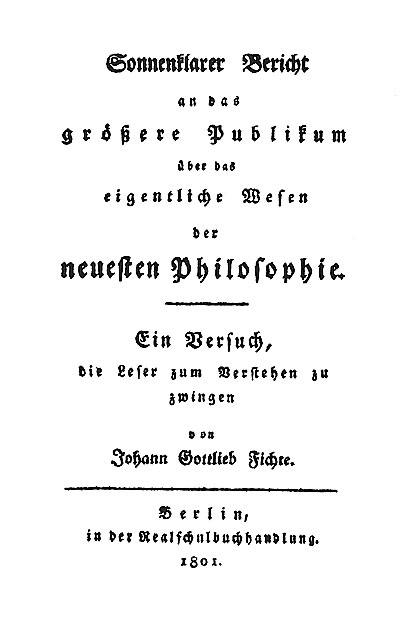

Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Sonnenklarer Bericht an das größere Publikum über das eigentliche Wesen der neuesten Philosophie (1801).

The Absolute I

A central core of Fichte’s philosophy is the concept of the “absolute I”. This absolute I is not to be confused with the individual spirit. Later he used the terms “absolute,””being,” or “God. Spruce begins in its basis of the entire science with a determination of the ego:

“The I sets itself, and it is capable of this mere setting by itself; and vice versa: The I is, and it sets its Seyn, capable of its mere Seyn. It is both the acting, and the product of action; the active, and that which is produced by action; action, and that is one and the same thing; and therefore this is: I am, expression of an action.”“[10]

Practical Implications

Fichte was concerned with the practical implementation of his philosophy, which is why he considered the establishment of a complete philosophical system to be of secondary importance. The comprehensibility of his teaching was in the foreground for him. He represented a positive image of man and assumed that in every man – and not only in the scholar – the foundation of true self-knowledge (and thus also Godknowledge) is laid and the philosopher only has to refer to it.

The Basis of all Science

Since Fichte quickly regarded his Basis of all Science (Grundlage der gesamten Wissenschaftslehre ) as insufficient and in need of supplementation, at the height of his Jena period he set about a new elaboration of science (under the name of Science Nova Methodo) and a first elaboration of practical philosophy (in the basis of natural law and morals) at almost the same time. In terms of content, the question has arisen since the foundation of the entire theory of science as to why the absolute self, which is autonomous, reacts to an “impulse”. Fichte makes it clear that the absolute ego is only when it becomes conscious of itself. This can only happen when it is confronted with material to which it has to react. If there were no contact, the ego would be “completely absorbed in its activity”. Fichte employed the triadic idea “thesis–antithesis–synthesis” as a formula for the explanation of change. Fichte was the first to use the trilogy of words together, in his Grundriss des Eigentümlichen der Wissenschaftslehre, in Rücksicht auf das theoretische Vermögen (1795, Outline of the Distinctive Character of the Wissenschaftslehre with respect to the Theoretical Faculty):

“Die jetzt aufgezeigte Handlung ist thetisch, antithetisch und synthetisch zugleich.”

[“The action here described is simultaneously thetic, antithetic, and synthetic.”]

The triad thesis, antithesis, synthesis is often used to describe the thought of German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.[8] However, Hegel never used the terms himself, as instead his triad was concrete, abstract, absolute.

On the Ground of Our Belief in a Divine World-Governance

After publication of his essay “Ueber den Grund unsers Glaubens an eine göttliche Weltregierung” (On the Ground of Our Belief in a Divine World-Governance) in 1798, in which he wrote that God should be conceived primarily in moral terms: “The living and efficaciously acting moral order is itself God. We require no other God, nor can we grasp any other.“, he was finally dismissed from Jena in 1799 as a result of a charge of atheism. Since all the German states except Prussia had joined in the cry against him, he was forced to go to Berlin. In 1805, Fichte was appointed to a professorship in Erlangen. One year later, in 1806, Napoleon, who had brought war all over Europe, completely crushed the Prussian army in the battle of Jena-Auerstadt. The deplorable situation of Germany stirred him to the depths and led him to deliver the famous Addresses to the German Nation (1808) which guided the uprising against Napoleon. In 1810, the new University of Berlin was set up, designed along lines put forward by Wilhelm von Humboldt.[7] Fichte was made its rector and also the first Chair of Philosophy. This was in part because of educational themes in the Addresses, and in part because of his earlier work at Jena University.. When the campaign against Napoleon finally began in 1812, Fichte’s wife devoted herself to nursing, where she caught a virulent fever. Just as she was recovering, Fichte himself was stricken down and died in 1814 at age only 51.

“The Doctrine of Knowledge, apart from all special and definite knowing, proceeds immediately upon Knowledge itself, in the essential unity in which it recognises Knowledge as existing; and it raises this question in the first place — How this Knowledge can come into being, and what it is in its inward and essential Nature?”

–Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Outline of the Doctrine of Knowledge (1810)

Prof. Fred Amrine – “Kicking Away the Ladder”, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- [2] Works by Johann Gottlieb Fichte, original German texts

- [3] Internationale Johann Gottlieb Fichte Gesellschaft

- [4] Johann Gottlieb Fichte at Wikidata

- [5] Immanuel Kant – Philosopher of the Enlightenment, SciHi Blog

- [6] Wilhelm von Humboldt and Prussia’s Education System, SciHi Blog

- [7] Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel and the Secret of his Philosophy, SciHi Blog

- [8] Cogito Ergo Sum – René Descartes, SciHi Blog

- [9] Timeline for German Idealism, via DBpedia and Wikidata

- [10] Prof. Fred Amrine – “Kicking Away the Ladder”, Footnotes2Plato @ youtube

- [11] Karl Ameriks, Dieter Sturma (eds.), The Modern Subject: Conceptions of the Self in Classical German Philosophy, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

- [12] Frederick Neuhouser. Fichte’s Theory of Subjectivity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- [13] Works by or about Johann Gottlieb Fichte at Internet Archive

- [14] Works by or about Johann Gottlieb Fichte at Wikisource