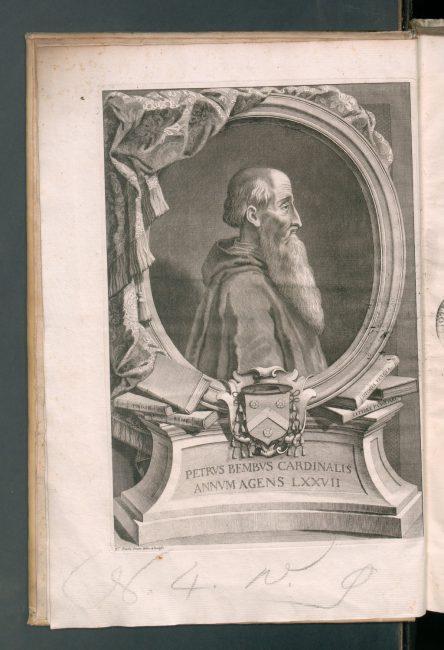

Cardinal Pietro Bembo (1470-1547)

On May 20, 1470, Italian scholar, poet, literary theorist, member of the Knights Hospitaller and cardinal Pietro Bembo was born. Bembo was an influential figure in the development of the Italian language, specifically Tuscan, as a literary medium, codifying the language for standard modern usage. His writings assisted in the 16th-century revival of interest in the works of Petrarch.

“Love can only be conquered by flight.”

— Pietro Bembo

Offspring of a Prestigious Venetian Family

Pietro Bembo came from a prestigious patrician family in Venice. His father Bernardo Bembo was a humanist and a friend of the humanist Marsilio Ficino; as Senator, Ambassador of the Republic of Venice and member of the Council of Ten, he was one of the leading politicians of his hometown. Until 1480 Pietro Bembo lived in Florence, where his father was Venetian envoy. This brought him into contact with the Florentine dialect, which would later shape his concept of Italian as a written language. In 1492 he went to Messina to learn the ancient Greek language from the Greek scholar Constantine Laskaris.There he met Cola Bruno, a young Messinian, who became his lifelong companion, confidante and secretary.

The Study of Philosophy

In 1494 he went to Padua to study philosophy. In 1496, with the Venetian printer Aldo Manuzio Bembos published his first work De Aetna, a Latin report in dialogue with his father about an ascent of Etna. In 1497 he went to Ferrara to continue his philosophy studies, where his father worked as a diplomat at that time. There, Bembo made friends with the courtier and poet Ercole Strozzi, the humanist and later Cardinal Jacopo Sadoleto and the poet Ludovico Ariosto.[1]

The Love Affair with Maria Savorgnan

His love affair began in 1500 with Maria Savorgnan, the widow of an officer. About 160 letters he wrote to and received from Mary have survived; even private letters from humanists were then considered literary works and kept for later publication.The letters aroused the admiration of Lord Byron in the 19th century as a result of the love affair with her.

A Brilliant Career in Rome

From 1500 Bembo had already applied in vain for jobs and commissions in the diplomatic service; after the repeated failures he changed his life plan and decided for a church career.In 1506 he accepted an invitation from the Duchess Elisabetta Gonzaga of Urbino, which was very helpful for Bembo’s ecclesiastical career, for Duke Guidobaldo was a close ally of the new Pope Julius II. He won the favour of Cardinal Galeotto Franciotti della Rovere, a relative of the Pope, whose intercession gave him his first benefice. In 1511 Bembo moved to Rome. When Leo X of the Medici family was crowned Pope in, 1513, the way opened for Bembo to a brilliant career. Bembo was appointed secretary of the Brevians, being responsible for the drafting of papal documents in Latin; this office he owed to his reputation as an excellent stylist.

Pietro Bembo Far from the Curia

In 1518 Bembo fell seriously ill, and in the following years he suffered from considerable health problems and had to leave the Pope’s service in 1521. At that time he had already accumulated 27 benefices, and Pope Leo X allowed him in gratitude for the services rendered to bequeath the benefices as private property at his discretion. In 1522 he was forced to join the Order of St. John in order to retain his lucrative benefices belonging to the Order. Although he had not yet become a priest, this was connected with the delay in his profession (religious vows). Among them was the vow of chastity, which he did not intend to fulfill, for he had already had a lover. Those years, which Bembo spent far from the curia – mostly in Padua – were a time of intense literary work. In his residence in Padua he collected precious works of art, antiques, books and manuscripts. In 1530, the Republic of Venice entrusted him with the post of librarian at the Biblioteca Nicena, later to become Biblioteca Marciana, and appointed him its official historian.

Bembo’s portrait, Historia veneta (1729)

A New Pope

In 1534, the election of Pope Paul III gave him a chance to resume his ecclesiastical career, which was interrupted by the death of Leo X. On 19 March 1539 Bembo was proclaimed Cardinal and received the title church of San Crisogono, whereupon he moved from Padua to Rome and was ordained priest. Neither his unchaste past nor the secular and partly erotic character of his works proved to be an obstacle; the reason given for his elevation to cardinal was that he could easily be regarded as the prince of his age in scholarship and linguistic art.

Reformation

Bembo was hardly interested in theology. Therefore, the ideas of the beginning Reformation played a very minor role in his private correspondence. In the dispute over the doctrine of justification, he apparently tended to compromise with the Lutherans. He maintained unbiased contact with people influenced by Protestant ideas, some of whom were later persecuted by the Inquisition after his death.

Later Life

In 1521 Bembo had taken the view that Luther’s theses should be openly discussed, and as Cardinal he showed great admiration for the efforts of his colleague Gasparo Contarini at the Regensburg Religious Talks of 1541, he belonged to the minority in the College of Cardinals that supported Contarini. In 1541 he became Bishop of Gubbio, where he finished his portrayal of Venetian contemporary history. Already in 1544 he received the diocese of Bergamo, which was much more important than Gubbio, and in the same year the Pope called him back to Rome. In the eighth decade of his life, he continued his literary work without any signs of fatigue or weakening of mental tension.It was not until he fell fatally ill that his restless activity ended. He died on January 18, 1547 in Rome.

The Italian Vernacular

Bembo’s works are partly in Latin and partly in Italian. His literary concept is based on the principle of a congenial, consistent imitation of the best model for prose or poetry in the respective language. Only in this way did he think he could achieve the unity of style in which he saw a prerequisite for mastery. He was thus one of the linguistic purists and classicists who did not want to tolerate anything incompatible with the style of “classical” authors. He always represented his convictions in a clear, decisive tone. He used to revise his texts constantly. Besides Latin, the traditionally preferred language of the humanists, Bembo also appreciated the Italian vernacular; he regarded it as equivalent to Latin. With his theory of language and silence he wanted to give it a basis for its function as a literary language and show that it is suitable for literary purposes.

Cicero, Petrarch, Boccaccio and Machiavelli

Bembo’s linguistic study Prose della volgar lingua (“Treatise on the vernacular“) appeared in Venice in 1525. The literary framework is a dialogue between four humanists, including Benbo’s brother Carlo, whom he puts his own view into his mouth. In the first book, the starting point is a comparison between the Latin and Italian languages and the related question of the value of Italian as a literary language. In connection with this, the general question arises as to the relationship between natural, spoken language and an elevated written language. The fact that important writers made use of Italian proves its suitability for literary language. Like Latin, Bembo sees Italian as defined by classical models that have brought the vernacular to perfection, just as Cicero sees Latin.[2] For him these are Petrarch and Boccaccio;[3,4] his relationship with Dante, on the other hand,[5] to whose vocabulary he has some objections, is distanced. Petrarch should be the authoritative model for poetry, Boccaccio for prose. In the third book he deals in detail with grammatical questions, thereby making an important contribution to the standardization of Italian grammar. Since the models used the Tuscan language, the “language dispute” (questione della lingua), the rivalry between the regional expressions of Italian, was decided in favour of Tuscan, in favour of the expression of the 14th century, which was already somewhat antiquated in the early modern period. Thus, in the language dispute, Bembo takes a counterposition to Machiavelli, who did not want an ancient language, and to Castiglione and Trissino, who advocated a mixture of different regional influences in the high-level language.[6]

Ramie Targoff, Renaissance Woman: The Life of Vittoria Colonna, [11]

References and Further Readings:

- [1] Ludovico Ariosto and the Frenzy of Orlando, SciHi Blog

- [2] Marcus Tullius Cicero – a Homo Novus, SciHi Blog

- [3] Francesco Petrarca – Father of Renaissance, SciHi Blog

- [4] Boccaccio and his Decameron, SciHi Blog

- [5] Dante Alighieri and the Divine Comedy, SciHi Blog

- [6] Reckless Power Play Politics – Niccolò Machiavelli, SciHi Blog

- [7] Works by or about Pietro Bembo at Internet Archive

- [8] Burke, Edmund (1907). “Pietro Bembo“. In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- [9] Pietro Bembo at Wikidata

- [10] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [11] Ramie Targoff, Renaissance Woman: The Life of Vittoria Colonna, CasaItalianaNYU @ youtube

- [12] Early Italian Historians, born before 1700, via DBpedia and Wikidata