Johann Beckmann (1739–1811)

On June 4, 1739, German chemist and economist Johann Beckmann was born. He established the science of agriculture and coined the word technology, to mean the science of trades. Technology today has become ubiquituous. You might think that this term was part of our vocabulary ever since antiquity. Not at all. It was Johann Beckmann, who was the first to teach technology and write about it as an academic subject.

Johann Beckmann and the Age of Enlightenment

Johann Beckmann was born at Hoya in Hannover, Germany. He attended the local public Latin school and then enrolled at the University of Göttingen, where he studied theology, mathematics, physics, natural history, and public finance and administration. After graduating, Beckmann made a study tour through Brunswick and the Netherlands examining mines, factories and natural history museums. Further study trips took him to some of the most important universities in Europe at the time.

Teaching in St Peterburg and Göttingen

In 1762, Beckmann’s mother passed away and due to his lack of support, Beckmann was invited by the pastor of the Lutheran community, Anton Friedrich Büsching, the founder of the modern historic statistical method of geography, to teach natural history in the Lutheran gymnasium St. Petrischule in St Petersburg, Russia. He stayed there until 1765 and traveled to Denmark and Sweden afterwards. Beckmann studied the methods of working the mines, factories and foundries as well as collections of art and natural history and also made the acquaintance of Linnaeus at Uppsala.[1] Johann Beckmann then returned to Göttingen, where he was appointed extraordinary professor of philosophy. He also lectured in the field of political and domestic economy, and in 1768 he founded a botanic garden on the principles of Linnaeus. His activities at Göttingen were to successful that in 1770 he was appointed ordinary professor. Soon he became so well-known that students from all parts of Europe – among them Alexander von Humboldt – attended his lectures in Göttingen. He published his essential findings in 1769 in the textbook Grundsätze der teutschen Landwirthschaft.[3]

Scientific Technology

It is believed that Beckmann used quite novel methods of teaching, taking his students to the workshops, that they might acquire a practical as well as a theoretical knowledge of different processes and handicrafts. However, Beckmann noticed that his industry and enthusiasm were unable to overtake the amount of study necessary for this task. He confined his attention to several practical arts and trades and as a result, he published his ‘Beiträge zur Geschichte der Erfindungen‘, translated into English as the History of Inventions, discoveries and origins. This work entitles Johann Beckmann to be regarded as the founder of scientific technology, a term which he was the first to use in 1772. It is believed that in his work, Beckmann was inspired by Diderot [6] as well as Linnaeus, and Albrecht von Haller.[2] To this end, he systematically examined manual activities according to technical principles in order to describe how production could be made more efficient through the use of suitable processes and tools. In his lectures on economics, Beckmann combined theory and practice by illustrating the path of a product from raw material to processing, sale and proper use. Beckmann produced the first known work of historical and critical accounts of the techniques of craft and manufacture and publish classifications of techniques.

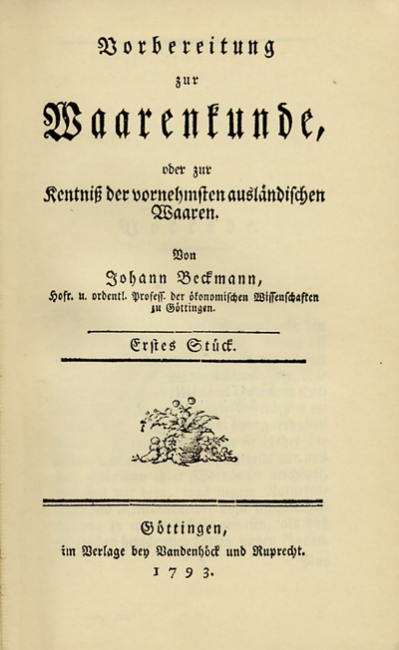

Johann Beckmann: Vorbereitung zur Waarenkunde, 1793, title page

Honours

Beckmann was elected a member of the Royal Society of Göttingen in 1772 and continued to contribute valuable scientific dissertations to its proceedings until 1783. Also, Johann Beckmann was member of scientific societies in Celle, Halle, Munich, Erfurt, Amsterdam, Stockholm and St Petersburg. In 1784, he was appointed a Councillor to the Hanoverian Court. In 1790, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Death

Johann Beckmann died on 3 February 1811. Other important works of Beckmann are Entwurf einer allgemeinen Technologie (1806); Anleitung zur Handelswissenschaft (1789); Vorbereitung zur Warenkunde (1795-1800); Beiträge zur Ökonomie, Technologie, Polizei- und, Kameralwissenschaft (1777-1791).

Kevin Kelly: How technology evolves, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Carl Linnaeus – ‘Princeps Botanicorum’, the Prince of Botany, SciHi Blog

- [2] Albrecht von Haller – Father of Modern Physiology, SciHi Blog

- [3] On the Road with Alexander von Humboldt, SciHi Blog

- [4] Works of Johann Beckmann at Wikisource

- [5] Johann Beckmann at Wikidata

- [6] Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, SciHi Blog

- [7] Works by Johann Beckmann at German Digital Library

- [8] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [9] De historia naturalis veterum libellus primus (la). Johann Christian Dieterich, Sankt-Peterburg 1766.

- [10] Anfangsgründe Der Naturhistorie. Georg Ludewig Försters, Göttingen 1767.

- [11] Kevin Kelly: How technology evolves, 2007, TED @ youtube

- [12] Carl Graf von Klinckowstroem: Beckmann, Johann. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6, S. 727 f.

- [13] Timeline of Historians of Science, via DBpedia and Wikidata