Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) by Charles Thévenin, 1802

On August 1, 1744, French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was born. Lamarck was an early proponent of the idea that evolution occurred and proceeded in accordance with natural laws. He gave the term biology a broader meaning by coining the term for special sciences, chemistry, meteorology, geology, and botany-zoology.

“Do we not therefore perceive that by the action of the laws of organization . . . nature has in favorable times, places, and climates multiplied her first germs of animality, given place to developments of their organizations, . . . and increased and diversified their organs? Then. . . aided by much time and by a slow but constant diversity of circumstances, she has gradually brought about in this respect the state of things which we now observe. How grand is this consideration, and especially how remote is it from all that is generally thought on this subject!” (from a Lecture of Lamarck, 1803)

Lamarck’s Education

Jean Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de Lamarck was born in the village of Bazentin-le-Petit in the north of France, as the youngest of eleven children in a family with a centuries-old tradition of military service. The young Lamarck entered the Jesuit seminary at Amiens around 1756, but not long after his father’s death, Lamarck joined the French army campaigning in Germany in the Pomeranian War (1757-1762) with Prussia in the summer of 1761. In his very first battle, he distinguished himself for bravery under fire and was promoted to officer. After spending five years on garrison duty in Monaco in the south of France and after working as a bank clerk in Paris for a while, Lamarck began to study medicine and botany under Bernard de Jussieu, a notable French naturalist. In 1778 his book on the plants of France, Flore Française, was published as a three-volume work to great acclaim, in part thanks to the support of Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon.[5]

The Jardin des Plantes

With Buffon‘s help who also supported Lamarck‘s membership to the French Academy of Sciences in 1779, Lamarck was appointed an assistant botanist at the royal botanical garden, the Jardin des Plantes, which was not only a botanical garden but a center for medical education and biological research.[5] Lamarck continued as an underpaid assistant at the Jardin du Roi, living in poverty (and having to defend his job from cost-cutting bureaucrats in the National Assembly) until 1793.[1] That year, the same year that Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette went to the guillotine, the old Jardin des Plantes was reorganized as the Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History). Lamarck had worked as the keeper of the herbarium for five years and now he was appointed curator and professor of invertebrate zoology, a subject he knew nothing about. The word “invertebrates” did not even exist at the time, and since the time of Linnaeus, few naturalists had considered the invertebrates worthy of study.[4] However, Lamarck coined the term and today, he is often referred to as chief founder of the field of invertebrate paleontology.[2]

The Idea of Evolution

“What nature does in the course of long periods we do every day when we suddenly change the environment in which some species of living plant is situated.”

– Jean Baptiste Lamarck, Philosophie Zoologique, Vol. I (1809)

In his first six years as professor, Lamarck published only one paper, in 1798. He began as an essentialist who believed species were unchanging. However, after working on the molluscs of the Paris Basin, he grew convinced that transmutation or change in the nature of a species occurred over time. He set out to develop an explanation, and on 11 May 1800, he presented a lecture at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in which he first outlined his newly developing ideas about evolution. Lamarck published a series of books on invertebrate zoology and paleontology. Of these, Philosophie zoologique, published in 1809, most clearly states Lamarck‘s theories of evolution.

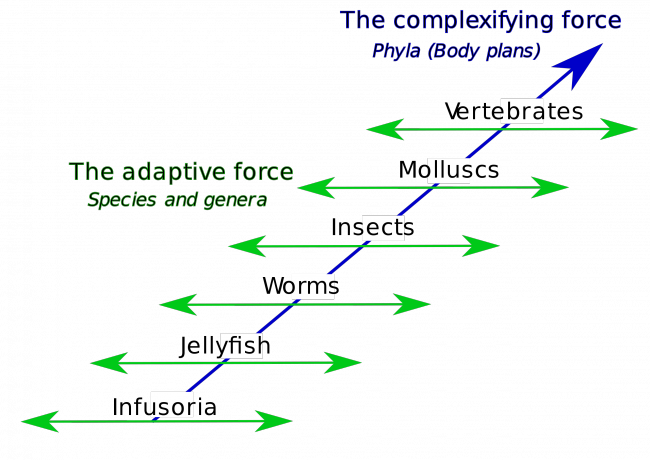

Lamarck’s two-factor theory involves 1) a complexifying force that drives animal body plans towards higher levels (orthogenesis) creating a ladder of phyla, and 2) an adaptive force that causes animals with a given body plan to adapt to circumstances (use and disuse, inheritance of acquired characteristics), creating a diversity of species and genera

In his theory, Lamarck assumed that simple microscopic forms of life continuously arise spontaneously from nonliving matter. This notion that spontaneous generation occurs on an ongoing basis was still widely accepted in his day. But he further supposed that such forms had an innate tendency gradually to evolve over time into organisms of ever greater complexity. This was something no one else had said.[2] Life became successively diversified, he claimed, as the result of two very different sorts of causes. He called the first “the power of life,” or the cause that tends to make organization increasingly complex,” whereas he classified the second as the modifying influence of particular circumstances (that is, the effects of the environment).[3]

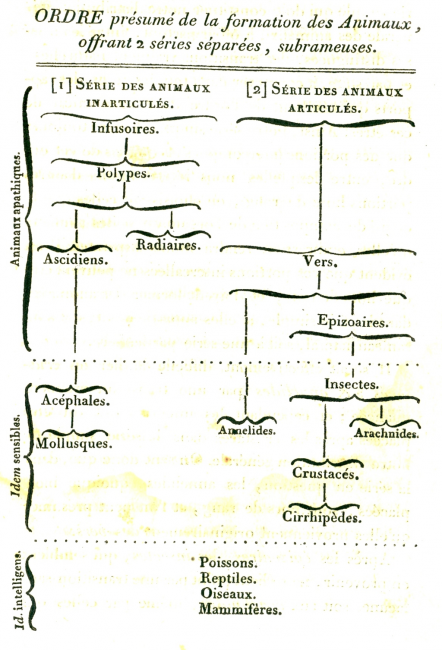

Branching diagram depicting two series of animal origins, from the Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1815)

By Lamarck’s account, animals, in responding to different environments, adopted new habits. Their new habits caused them to use some organs more and some organs less, which resulted in the strengthening of the former and the weakening of the latter. New characters thus acquired by organisms over the course of their lives were passed on to the next generation (provided, in the case of sexual reproduction, that both of the parents of the offspring had undergone the same changes). Small changes that accumulated over great periods of time produced major differences. Lamarck thus explained how the shapes of giraffes, snakes, storks, swans, and numerous other creatures were a consequence of long-maintained habits.[3]

“Lamarck was the first man whose conclusions on this subject excited much attention…[H]e upholds the doctrine that all species, including man, are descended from other species. He first did the eminent service of arousing attention to the probability of all changes in the organic, as well as in the inorganic world, being the result of law, and not of miraculous interposition.”(Charles Darwin, The Origin of species, 3rd ed., p. xiii)

Lamarck’s Legacy

Later in the century, after English naturalist Charles Darwin advanced his theory of evolution by natural selection, the idea of the inheritance of acquired characters came to be identified as a distinctively “Lamarckian” view of organic change (though Darwin himself also believed that acquired characters could be inherited).[6] The idea was not seriously challenged in biology until the German biologist August Weismann did so in the 1880s. In the 20th century, since Lamarck’s idea failed to be confirmed experimentally and the evidence commonly cited in its favour was given different interpretations, it became thoroughly discredited. Epigenetics, the study of the chemical modification of genes and gene-associated proteins, has since offered an explanation for how certain traits developed during an organism’s lifetime can be passed along to its offspring.[3]

The End

Lamarck gradually turned blind and died in Paris on December 18, 1829. When he died, his family was so poor they had to apply to the Academie for financial assistance. Lamarck’s books and the contents of his home were sold at auction, and his body was buried in a temporary lime-pit. In his own day, Lamarck’s theory of evolution was generally rejected as implausible, unsubstantiated, or heretical. Today he is primarily remembered for his notion of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. During his lifetime, Lamarck named a large number of species, many of which have become synonyms. The World Register of Marine Species gives no fewer than 1,634 records. The Indo-Pacific Molluscan Database gives 1,781 records

Who was Lamarck? And what did he think?, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Jean-Baptiste Lamarck at UCMP Berkeley

- [2] Eugene M. McCarthy: Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, at famous biologists on marcoevolution.net

- [3] Jean-Baptiste Lamarck at Britannica Online

- [4] How a Cobbler became the Princeps Botanicarum – Carl Linnaeus, SciHi Blog

- [5] Comte de Buffon and his Histoire Naturelle, SciHi Blog

- [6] Charles Darwin and the Natural Selection, SciHi Blog

- [7] Works by or about Jean-Baptiste Lamarck at Internet Archive

- [8] Jean-Baptiste Lamarck: works and heritage, online materials about Lamarck (23,000 files of Lamarck’s herbarium, 11,000 manuscripts, books, etc.) edited online by Pietro Corsi (Oxford University) and realised by CRHST-CNRS in France.

- [9] Lamarck and Natural Selection, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Sandy Knapp, Steve Jones and Simon Conway Morris (In Our Time, 26 December 2003)

- [10] Jean-Baptiste Lamarck at Wikidata

- [11] Who was Lamarck? And what did he think?, Scott Turner @ youtube

- [12] Cuvier, Georges (January 1836). “Elegy of Lamarck”. Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. 20: 1–22.

- [13] Packard, Alpheus Spring (1901). Lamarck, the founder of Evolution: his life and work with translations of his writing on organic evolution. New York: Longmans, Green.

- [14] Timeline for Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #04 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #51 | Whewell's Ghost