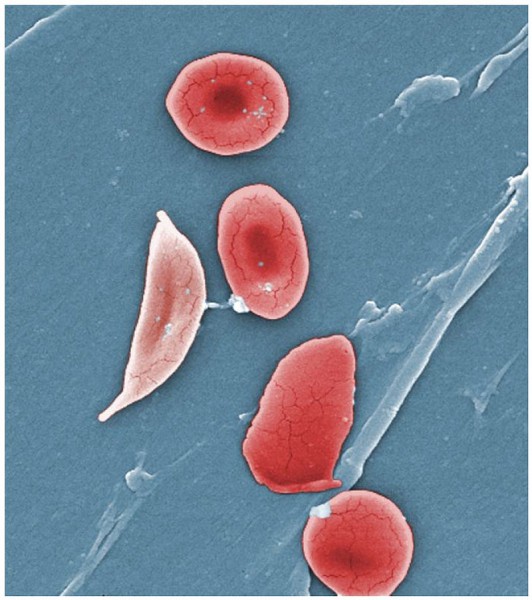

Normal blood cells next to a sickle-blood cell, colored scanning electron microscope image

On August 11, 1861, American physician James Bryan Herrick was born. He is credited with the description of sickle-cell disease, which results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red blood cells, and was one of the first physicians to describe the symptoms of myocardial infarction.

Education and Academic Career

James Bryan Herrick was born in Oak Park, Illinois, to Origen White Herrick and Dora Kettlestrings Herrick. He attended Oak Park and River Forest High School and nearby Rock River Seminary. He received a BA degree from the University of Michigan in 1882, after which he taught school in Peoria, Illinois and Oak Park. After a few years of teaching in the public schools he entered Rush Medical College, and received his M.D. in 1888. He interned at Cook County Hospital, after which he opened a private practice in the Chicago area. Like many clinicians with a bent toward research, he traveled to Europe where he worked with the renowned pathologist Hans Chiara for three months in Prague. Several years later he spent time in a Vienna clinic.[4] He also obtained a part-time teaching position at Rush College, and was listed as a full Professor there from 1900 through 1927. He was also on the staff of Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago from 1895 through 1945.

Unusual Sickle-shaped Erythrocytes

His practice, originally in general medicine, soon developed into a specialization in internal medicine, with a particular emphasis on cardiovascular diseases.[1] His first discovery, in 1910, he described the unusual sickle-shaped erythrocytes found in a blood smear from Walter Clement Noel, an anemic young black Caribbean dental student from the island of Grenada, who originally had a sore on his ankle and evidence of previous scarring and now developed severe respiratory problems.[2,4] When Herrick saw this in the chart, he became interested because he saw that this might be a new, unknown, disease. He subsequently published a paper in one of the medical journals in which he used the term “sickle shaped cells”.[3]

Herrick’s Syndrome

Herrick’s description of the student’s disease was known for many years as Herrick’s syndrome, and is now known as sickle-cell disease. The condition is prevalent in West Africa and is genetically passed down. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red blood cells. This leads to a rigid, sickle-like shape under certain circumstances. In 1927, Hahn and Gillespie discovered that red blood cells from persons with the disease could be made to sickle by removing oxygen. This was exciting because red cells are the oxygen transporters of the body. The trouble was, that there were people – often relatives of the patient – whose red cells had this trait of sickling when deprived of oxygen but who had no disease. This condition became known as “sickle trait”.[3] As of 2013 about 3.2 million people have sickle-cell disease while an additional 43 million have sickle-cell trait.

A Landmark Article on Myocardial Infarction

Herrick’s second major contribution was a landmark article on myocardial infarction (“heart attack”) in JAMA in 1912. He proposed that thrombosis in the coronary artery leads to the symptoms and abnormalities of heart attacks and that this was not inevitably fatal. While Herrick was not the first to propose this, ultimately his article was the most influential, although at the time it received only limited attention. The first case of coronary thrombosis described ante mortem was presented in 1878 by Adam Hammer, and the first completed description of the disease was published in 1910 by Obrastzow and Straschecko.[4] In 1918 he was one of the first to encourage electrocardiography in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction.

Later Years

Herrick is not closely associated with genetics, but his discoveries turned out to be inherited traits, so his contributions pointed other researchers toward genetically-based conditions. Herrick’s many achievements in later years included becoming president of the Association of American Physicians in 1923, and receiving the Kober Medal in 1930 from the Association, its highest award, for his work on cardiovascular disease.[4] Herrick died on March 7, 1954, in Chicago.

Jeffrey Glassberg, Sickle Cell Disease: Past, Present and Future [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] James Bryan Herrik, American physician, at Britannica Online

- [2] Thomas N. James: Homage to James B. Herrick: A Contemporary Look at Myocardial Infarction and at Sickle-Cell Heart Disease, at American Heart Association

- [3] William P. Winter: A Brief History of Sickle Cell Disease

- [4] Philip R. Liebson: James Bryan Herrick, at Hektoen International, A Journal of Medical Humanities

- [5] James Brian Herrick at Wikidata

- [6] Works by or about James B. Herrick at Internet Archive

- [7] Guide to the James Brian Herrick Papers 1886-1953 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

- [8] Jeffrey Glassberg, Sickle Cell Disease: Past, Present and Future, Icahn School of Medicine @ youtube