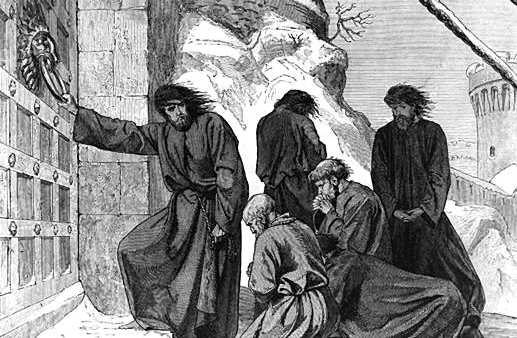

Henry IV and his entourage at Canossa Gate. 19th century depiction

On January 25, 1077, Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV arrived at the gates of the fortress at Canossa in Emilia Romagna beyond the Alpes to declare atonement and to pledge for forgiveness from Pope Gregory VII, who had excommunicated Henry earlier from church. Henry’s act of penance became known as the “Walk to Canossa”. It took wisdom, patience, and self-restraint. It was also a brilliant strategy because he basically forced the Pope to forgive him.

Becoming of Age

Konrad was the long desired first son of the emperor Henry III and Agnes von Poitou, he was baptized a few months after his birth and from then on called Heinrich (Henry). His father experienced several problems with the empire’s leaders due to their fear to lose power and authority. The young successor to the throne became King in 1054 and was engaged to Bertha von Turin in the following year. When Henry III passed away in 1056, his son was to follow his footsteps, but due to him being a child of only six years, Agnes von Poitou took over all governing tasks with the help of Pope Viktor II. Her regency was fulfilled with distrust and various rumors concerning her relationship with the Bishop of Augsburg. In 1062, the young King was kidnapped followed by the change of power to Anno II of Cologne. Only four years later, Henry IV was finally declared of age. He married Bertha of Turin and in concerns of governmental issues, he attempted to make the national boundaries stronger while reducing the opposition. He struggled against the Lutici and Otto of Nordheim, the duke of Bavaria. Rumors spread that the duke plotted against Henry IV, wherefore he was deposed from Bavaria.

Duelling with the Pope

During the reign of Henry’s father, the church’s reformation was being planned and the Tuscan monk Hildebrand ascended papacy as Gregory VII in 1073. Gregory VII’s and Henry IV’s interests moved apart, resulting in growing tensions between the Church and the Empire. Henry continued to interfere in Italy and Germany while Gregory excommunicated several members of the Imperial Court threatening to do so with Henry as well. During Christmas 1075, Gregory was kidnapped and imprisoned, which he put on Henry’s account and in the following year, Gregory VII was deposed on the behalf of Henry followed by the excommunication of the king.

Heinrich asks Mathilde and his godfather Abbot Hugo von Cluny for mediation. The caption reads, “The king makes a request to the abbot and humbly kneels before Mathildis.” (Rex Rogat abbatem Mathildim supplicat atque.) (Vita Mathildis of Donizo, ca. 1115. Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms. Vat. lat. 4922, fol. 49v)

Henry Gives In

Henry decided to move to Italy and crossed the Alps barefooted and only dressed with a hairshirt. After reaching Pavia, Gregory hid in the castle of Matilda of Tuscany in Canossa with Henry’s troops not far away. Henry was about to perform the penance to Gregory, assuring his continued rule, but when he reached Canossa they were refused entry. It was delivered that Henry stood outside the gates for three full days, fasting and freezing. On the third day, the gates of Canossa finally opened and Henry knelt before Pope Gregory, who invited him back into the church right after. The end of Henry’s excommunication was declared and he was able to return to the empire.

Going to Canossa

The saying ‘Going to Canossa’ from then on refers to the act of penance used numerous times in history. However, for Henry not everything turned out so well afterwards. Even though he was restored in Church, he did not receive the right to the throne and he was forced into civil war with Duke Rudolph of Swabia resulting in a further excommunication against Henry. Henry won the civil war and forced Gregory to flee. Henry IV passed away on August 7, 1106 and was succeeded by his son Henry V.

Contemporary Assessment

From a medieval point of view, the waiting of several days in a penitential shirt in front of the castle (January 25-28, 1077) to persuade the Pope to lift the ecclesiastical ban represents only a formal act of penance, which was customary and strictly formalized. The very drastic and pictorial representation in the only detailed source by Lampert von Hersfeld, however, is evaluated by recent research as tendentious and propagandistic, since Lampert was a partisan of the Pope and the opposition of the nobility. The second important source for the passage to Canossa comes from Pope Gregory VII himself. He spread his version of the events in a letter to all archbishops, bishops and other spiritual functionaries of the empire. According to Lampert’s account, the whole act had been negotiated in advance and its course had been determined, a practice of political communication in the Middle Ages that was quite common in the deditio. However, Henry IV regained a large part of his freedom of action through the abolition of the ban, and had thus finally achieved his goal.

Michele K. Spike, Matilda of Canossa: the life of a woman who changed the course of history, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Der Gang nach Canossa und die Erschütterung der Welt von Christiane Ruhmann – Heimatpflege in Westfalen, 19. Jahrgang – 2/2006 [In German] [PDF]

- [2] Ralf-Peter Märtin: Zeitläufte. Der König kniet… [In German]

- [4] The Golden Bull and the Holy Roman Empire, SciHi Blog, December 25, 2017

- [5] Otto the Great – Founder of the Holy Roman Empire, SciHi Blog, November 23, 2012

- [6] Charlemagne and the Birth of Europe, SciHi Blog, December 25, 2012.

- [7] Road to Canossa at Wikidata

- [8] Michele K. Spike, Matilda of Canossa: the life of a woman who changed the course of history, 2020, The Churches Conservation Trust @ youtube

- [9] Henry IV at Wikidata

- [10] Dante Bianchi, Matilde di Canossa e la Matelda dantesca. (in Italian) In: Studi matildici. Atti e memorie del convegno di studi Matildici, Modena/Reggio Emilia, 19-21 ottobre 1963. Modena 1964.

- [11] Holland, Tom. “Canossa: a Medieval clash between Church and State”, History Magazine. November 21, 2014

- [12] Timeline of Holy Roman Emperors, via Wikidata