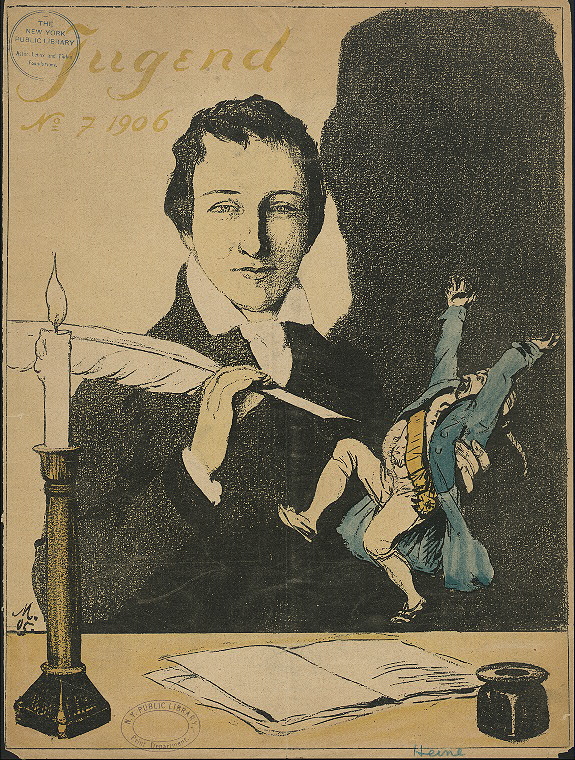

Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) on cover of ‘Die Jugend’, 1906

On December 12, 1797, Heinrich Heine, one of the most significant German poets of the 19th century was born. Besides, he was also a renowned journalist, essayist, and literary critic. But, he is best known for his wonderful lyric poetry, while his radical political views led to many of his works being banned by German authorities.

“Out of my own great woe

I make my little songs.”

— Heinrich Heine, Aus Meinen Grossen Schmerzen (Out of My Great Woe), st. 1

Family Background and Youth

Heinrich Heine was born in Düsseldorf, Rhineland, as the eldest of four children into a Jewish family. His father Samson Heine was a textile merchant, his mother Peira van Geldern was the daughter of a physician. He was called “Harry” as a child, but became “Heinrich” after his conversion to Christianity in 1825. By the time, his hometown Düsseldorf was only a small town with about 16,000 inhabitants. The French Revolution and the subsequent Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars which also involved Germany lead to a more or less complicated political history for Düsseldorf during Heine’s childhood. Heine’s parents were not particularly devout Jews. When he was a young child they sent him to a Jewish school where he learned a smattering of Hebrew. Thereafter he attended Catholic schools. He was a precocious boy, educated in a desultory way by Roman Catholic monks and French philosophers with the result that he became a skeptic before he had any faith to lose.

Why does a poet start writing poetry?

Why does a poet start writing poetry? Of course – or let’s say most probably – there must have been some kind of love affair, at least if it comes to love poems. And Heine from early age on was very much attracted to the other sex. While preparing himself to become a merchant and learning English, French, and Italian, he began to write poetry under the inspiration of a child love for “Veronica,” probably also the “Reseda” of his early poems. He conceived a passing affection, too, for an executioner’s daughter, Josepha, the subject of several poems, of his “Dream Pictures,” and of the most exquisite passage in his memoirs. She was, he says, his “love’s purgatory” before he fell into love’s hell in his unrequited affection for his cousin Amalie at Hamburg, whither he went in 1816. For her, under the names Ottilie, Maria, Clara, Evelina, Agnes, Juliana, he voiced his passion in many beautiful songs.

Studies and Duels

He tried to set up a business in Hamburg in 1818, but he liked neither the business nor the city. He failed in business, and at the expense of his uncle, Amalie’s father, who aided him generously through life, he went in 1819 to study law at Bonn, where he came under the influence of philosopher August Wilhelm Schlegel.[4] But, Heine was more interested in studying history and literature than law. Schlegel gave lectures about the Nibelungenlied and Romanticism and although Heine later on would make fun of Schlegel, he found in him a sympathetic critic for his early verses. The same happened to another of his Bonn teachers, Ernst Moritz Arndt, whose nationalist views Heine repeatedly criticized in later poems and prose texts. During his time in Bonn, Heine translated works by the romantic English poet Lord Byron into German.[5]

After a year at Bonn, Heine left to continue his law studies at the University of Göttingen, where he was expelled from a student fraternity for anti-Semitic reasons. When Heine challenged another student, Wiebel, to a duel (the first of ten known incidents throughout his life), the authorities stepped in and Heine was suspended from the university for six months. After Heine had contracted a venereal disease in a brothel, the fraternity, to which he had joined in Bonn in 1819, ruled him out a little later because of “offence against chastity”. Thus, his uncle now decided to send him to the University of Berlin. In May 1823 Heine left Berlin for good and joined his family at their new home in Lüneburg, where he began to write the poems of the cycle “Die Heimkehr“.

Harzreise and First Literary Success

He returned to Göttingen but again soon got bored by the law. In September 1824 he decided to take a break and set off on a trip through the Harz mountains. On his return he started writing a famous account of it, “Die Harzreise“. Finally, in 1825 Heine took a degree in law with absolutely minimal achievement and was awarded a doctorate in law in July 1825. In the same year he began his lifelong business relationship with Julius Campe in Hamburg, whose publishing house published Heine’s works from then on. In October 1827, Hoffmann and Campe published the Book of Songs (Buch der Lieder), a complete edition of Heine’s poetry. In it, the basic motif of Heine’s unhappy, unfulfilled love returns in an almost monotonous way after his own confession. The publication established Heine’s fame and is still popular today. The romantic, often folk-song tone of these and later poems, which Robert Schumann, among others, set to music in his work Dichterliebe, not only hit the nerve of his time.

“Where they have burned books, they will end in burning human beings.”

— Heinrich Heine, Almansor: A Tragedy (1823)

Conversion to Protestantism

In that same year, in order to open up the possibility of a civil service career, closed to Jews at that time, he converted to Protestantism with little enthusiasm and some resentment. Disillusioned with Germany and in political disgrace because of his liberal sympathies, he left for Paris in 1831, where he supported the social ideals of the French Revolution of 1830, becoming for a time a Saint-Simonist. Here began his second phase of life and work. The French capital inspired Heine to a veritable flood of essays, political articles, polemics, memoirs, poems and prose. Heine increasingly took on the role of an intellectual mediator between Germany and France and for the first time presented his position in a pan-European framework. He acquainted the French public with German Romanticism and German philosophy.

Exile in France

As the towering figure of the revolutionary literary movement Young Germany (Junges Deutschland), he continued from Paris to disseminate French revolutionary ideas in Germany. In 1835 the German Parliament banned the works of Young Germany and thus, Heine’s book were also banned. Heine enjoyed life in the French capital and made contact with the greats of European cultural life living there, such as Hector Berlioz, Ludwig Börne, Frédéric Chopin, George Sand, Alexandre Dumas and Alexander von Humboldt. Gradually it became a matter of course that German authors of distinction as visitors to Paris also visited Heine.

One event which really galvanised him was the 1840 Damascus Affair in which Jews in Damascus had been subject to blood libel and accused of murdering an old Catholic monk. This led to a wave of anti-Semitic persecution. The French government, aiming at imperialism in the Middle East and not wanting to offend the Catholic party, had failed to condemn the outrage. On the other hand, the Austrian consul in Damascus had assiduously exposed the blood libel as a fraud. For Heine, this was a reversal of values: reactionary Austria standing up for the Jews while revolutionary France temporised. Heine responded by dusting off and publishing his unfinished novel about the persecution of Jews in the Middle Ages, Der Rabbi von Bacherach (The Rabbi of Bacherach).

“Great genius takes shape by contact with another great genius, but less by assimilation than by friction.”

— Heinrich Heine

Heine and Karl Marx

In October 1843, Heine’s distant relative and German revolutionary, Karl Marx, and his wife Jenny von Westphalen arrived in Paris after the Prussian government had suppressed Marx’s radical newspaper. The Marx family settled in Rue Vaneau. Marx was an admirer of Heine and his early writings show Heine’s influence. In December Heine met the Marxes and got on well with them. He published several poems, including Die schlesischen Weber (The Silesian Weavers), in Marx’s new journal Vorwärts (“Forwards“). Ultimately Heine’s ideas of revolution through sensual emancipation and Marx’s scientific socialism were incompatible, but both writers shared the same negativity and lack of faith in the bourgeoisie.

The “Mattress-Grave”

The French government granted Heine a pension and he was able to continue to print his works in Germany. In 1841 he married Crescentia Eugenie (Mathilde) Mirat in Saint-Sulpice. In May 1848, Heine, who had not been well, suddenly fell paralyzed and had to be confined to bed. He would not leave what he called his “mattress-grave” (Matratzengruft) until his death eight years later on February 17, 1856 in Paris. Three days later he was buried in the Montmartre cemetery.

“Experience is a good school. But the fees are high.”

— Heinrich Heine

Henry Abramson, Heinrich Heine: Poet of Judenschmerz Jewish Biography as History, [10]

References and further Reading:

- [1] Heinrich Heine biography at art directory

- [2] Heinrich Heine biography at dromo.info

- [3] Heinrich Heine biography at suite101.com

- [4] August Wilhelm Schlegel and his Shakespeare Translations, SciHi Blog

- [5] Wicked Lord Byron’s Wonderful Poetry, SciHi Blog

- [6] Karl Marx and Das Kapital, SciHi Blog

- [7] Works of and about Heinrich Heine, via Wikisource

- [8] Works by or about Heinrich Heine at Internet Archive

- [9] Heinrich Heine at Wikidata

- [10] Henry Abramson, Heinrich Heine: Poet of Judenschmerz Jewish Biography as History, 2014, Henry Abramson @ youtube

- [11] Galley, Eberhard (1969), “Heine, Heinrich”, Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 8, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 286–291

- [12] Prochnik, George (2020). Heinrich Heine: Writing the Revolution. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

- [13] Stigand, William (1880). The Life, Work, and Opinions of Heinrich Heine (two volumes). New York: J. W. Bouton.

- [14] Timeline for Heinrich Heine, via Wikidata

Pingback: S-a întâmplat în 13 decembrie 1797 - Jurnal Spiritual

Pingback: S-a întâmplat în 13 decembrie 1797 – Jurnal FM