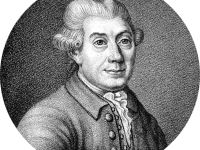

Heinrich Gustav Magnus (1802-1870)

On May 2, 1802, German physicist Heinrich Gustav Magnus was born. He is best known for the Magnus effect (the lift force produced by a rotating cylinder, which for example, gives the curve to a curve ball). In chemical research, he discovered the first of the platino-ammonium compounds.

Heinrich Gustav Magnus – Early Years

Heinrich Gustav Magnus’ father, the wealthy cloth and silk merchant Immanuel Meyer Magnus was baptized in 1807 with his sons in Berlin and acquired citizenship in 1809. In the same year he founded the banking house F. Mart in Berlin under his new name Johann Matthias Magnus. Magnus, which at times was one of the most important banks in Prussia. The upbringing and education of the sons was based on talent and inclination. While the two eldest sons took over the banking business and his brother Eduard Magnus embarked on a career as an artist, Gustav Magnus chose the natural sciences. Magnus attended the Friedrichswerdersche Gymnasium and then the Cauersche Anstalt. After completing his military service as a volunteer in the Guards Rifle Battalion, he studied chemistry, physics and technology at Berlin University from 1822. He received his doctorate in 1827 under Eilhard Mitscherlich with a thesis on the chemical element tellurium. Afterwards, Magnus traveled to Stockholm, working together with Jöns Jakob Berzelius [4] and later in Paris with Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac [5] and Louis Jacques Thénard. Heinrich Gustav Magnus was appointed first lecturer, later professor of physics and technology at the University of Berlin.

Magnus’ Laboratory

It is believed that Heinrich Gustav Magnus was a great teacher, able to stimulate and motivate his students which caused his rapid success. He was able to demonstrate the importance of applied science and held colloquies on physical questions at his own house. Magnus owned his laboratory privately (however, it was later integrated into the University of Berlin) and it became known as one of the best equipped in Europe. Beneficiaries of his lab include Hermann Helmholtz and Gustav Wiedemann.[6]

Chemical Research

As listed by the Royal Society of London, Magnus published 84 papers in research journals. In the 1820s and early 1830s, Magnus mainly devoted his time to chemical research questions, which resulted in the discovery of the first of the platino-ammonium class of compounds. Also, Magnus was able to identify the three sulfonic acids sulphovinic acid, ethanoic acid, and isethionic acid and their salts. Further research interests of Heinrich Gustav Magnus include the absorption of gases in blood as well as the expansion of gases by heat and the vapour pressures of water and various solutions in later years.

The Magnus Effect

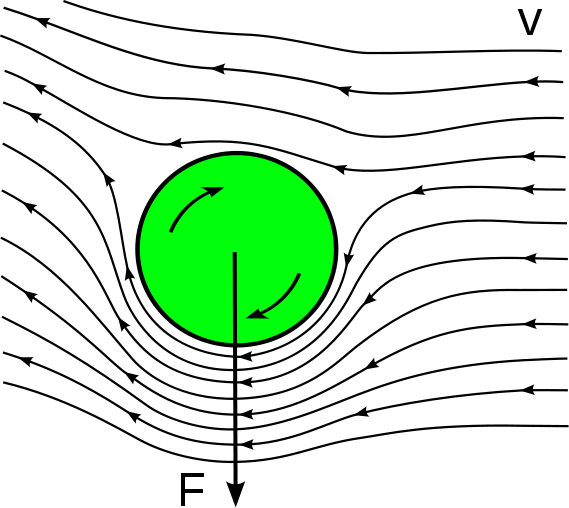

Named after the physicist is also the famous ‘Magnus effect‘ or sometimes called the Magnus force. He experimentally investigated the effect, it is responsible for the “curve” of a served tennis ball or a driven golf ball and affects the trajectory of a spinning artillery shell.

Magnus effect. In sum, the air flow around the side of the clockwise rotating cylinder, which rotates with the flow, is greater than on the other side causing a slight pressure difference. In the image that is on the underside of the cilinder, so that it experiences a downward force. The ball should have a horizontal speed -V toward RIGHT.

“A spinning object moving through a fluid departs from its straight path because of pressure differences that develop in the fluid as a result of velocity changes induced by the spinning body. The Magnus effect is a particular manifestation of Bernoulli’s theorem: fluid pressure decreases at points where the speed of the fluid increases. In the case of a ball spinning through the air, the turning ball drags some of the air around with it. Viewed from the position of the ball, the air is rushing by on all sides. The drag of the side of the ball turning into the air retards the airflow, whereas on the other side the drag speeds up the airflow. Greater pressure on the side where the airflow is slowed down forces the ball in the direction of the low-pressure region on the opposite side, where a relative increase in airflow occurs.“

…before Magnus

However, it is also believed that already Isaac Newton had described it 1672 and correctly inferred the cause after observing tennis players at Cambridge college. It is further assumed that also Benjamin Robins, a British mathematician, ballistics researcher, and military engineer, explained deviations in the trajectories of musket balls in terms of the Magnus effect in 1742. The knowledge of the connections between the asymmetry of the air flow surrounding a rotating body (cylinder or sphere) led Anton Flettner to invent a vertical axis rotor, the so-called Flettner rotor, which can be used for ship propulsion. Testing took place in the 1920s with moderate success. In 1985, after almost 60 years of standstill, Jacques Cousteau [7] took up the idea again and had his research ship Alcyone equipped with a drive system using the Magnus effect. The latest state of development is the cargo ship E-Ship 1 of the wind turbine manufacturer Enercon, which went into service in 2009.

The German RoLo cargo ship E-Ship 1 in the harbour of Emden with four Flettner rotors

Next to these studies, Heinrich Gustav Magnus was also active in the introduction of a uniform metric system of weights and measures into Germany. He built a maximum thermometer (geothermometer) to measure the heat inside the earth (e.g. in boreholes and mines). In 1861/1862 he held the office of rector of the university. After Humboldt’s death, Magnus initiated the establishment of the Humboldt Foundation, whose financial resources he secured. Heinrich Gustav Magnus passed away on April 4, 1870, at age 67.

Casey Harwood, Lecture 23 Magnus Effect and Viscous Flow Video and Slides Enhanced Quality, [13]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Magnus Effect at Britannica

- [2] Heinrich Gustav Magnus Biography

- [3] Heinrich Gustav Magnus – Life and Works

- [4] Jöns Jacob Berzelius – One of the Founders of Modern Chemistry, SciHi Blog

- [5] Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and his Work on Gases, SciHi Blog

- [6] Hermann von Helmholtz and his Theory of Vision, SciHi Blog

- [7] The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, SciHi Blog

- [8] Horst Kant: Ein Lehrer mehrerer Physikergenerationen – Zum 200. Geburtstag des Berliner Physikers Gustav Magnus

- [9] August Wilhelm von Hofmann (1884), “Magnus, Heinrich Gustav“, Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), 20, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 77–90

- [10] Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- [11] Heinrich Gustav Magnus at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- [12] Heinrich Gustav Magnus at Wikidata

- [13] Casey Harwood, Lecture 23 Magnus Effect and Viscous Flow Video and Slides Enhanced Quality, Casey Harwood @ youtube

- [14] George B. Kauffman, (1976), Gustav Magnus and his Green Salt, in Platinum Metals Review, vol 20(1).

- [15] Timeline of Experimental Physicists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Bibliographie/ Sitiographie | TPE: Les alvéoles d'une balle de golf

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #38 | Whewell's Ghost