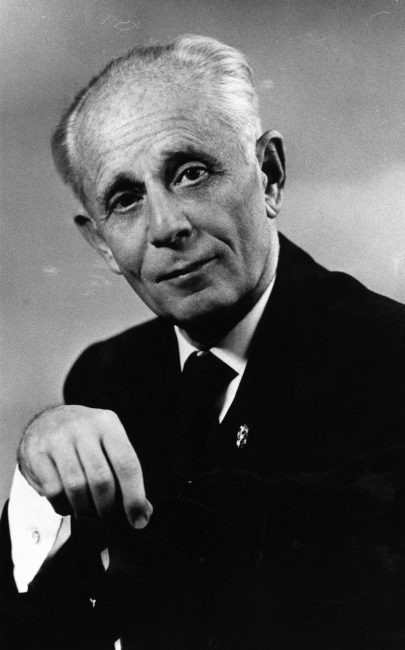

Hans Selye (1907 – 1982)

On January 26, 1907, pioneering Austrian-Canadian endocrinologist Hans Selye was born. He conducted much important scientific work on the hypothetical non-specific response of an organism to stressors. Although he did not recognize all of the many aspects of glucocorticoids, Selye was aware of their role in the stress response. He is considered the first to demonstrate the existence of biological stress.

Hans Selye – Early Years

Hans Selye was born in Vienna, Austria-Hungary, the only child of the Hungarian military surgeon Hugo Selye and Austrian Maria Felicitas, née Langbank. Because the Selye family was rather well-to-do, Hans Selye received a quality education and could, already at the age of four, speak four languages. Later, the family left Vienna and moved to Komárom, Hungary, where the young János finished his secondary education at the Benedictine Fathers’ College in Komárno. In 1924, he studied medical sciences at the German language university in Prague (Charles University in Prague) and then did internships in Paris and Rome, where he practiced his French and learned Italian. Selye became a Doctor of Medicine and Chemistry in Prague in 1929, and chose research rather than medical practice, much to the disappointment of his father who hoped to see him take over the family clinic.

Research Career

In 1931, he went to Johns Hopkins University on a Rockefeller Foundation Scholarship. Between 1934 and 1941, he was Assistant Professor of Biochemistry at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, where he started researching the issue of stress in 1936. In 1945, he accepted a position at the Faculty of Medicine of the Université de Montréal, where he founded the Institute of Experimental Medicine and Surgery (IMCE) of the Université de Montréal. He remained in this position until his retirement in 1977. During this time, he also served as General Surgical Advisor to the US Army.

Detecting Stress

Selye’s interest in stress began when he was in medical school; he had observed that patients with various chronic illnesses like tuberculosis and cancer appeared to display a common set of symptoms that he attributed to what is now commonly called stress. In his experiments, for instance, Selye injected mice with extracts of various organs. At first, the scientist believed to have discovered a new hormone. However, he later noticed that humans sometimes have the same symptoms and he then described the effects of “noxious agents” as he at first called it. He later coined the term “stress“.

Stress Adaption

Selye conceptualized the physiology of stress consisting of two components: the “general adaptation syndrome” as a set of responses, and the development of a pathological state from ongoing, unrelieved stress. According to Selye the general adaptation syndrome is triphasic:

- alarm reaction: the body reacts to a stressor to which it is not adapted. This phase includes a shock phase (state of surprise, symptoms of passive otherness) and a counter-shock phase (the body defends itself against the aggression) in response to the shock phase ;

- resistance phase: continuation of the counter-shock phase, the organism adapts to the stressing agent which is prolonged ;

- exhaustion phase: threshold where the body ceases to be able to adapt to the stimulus caused by the stressor. This phase leads to exhaustion of the body and can lead to serious disorders and illnesses, even death.

These phases were established largely on the basis of glandular states. Selye further made the discovery that there are different kinds of stress depending on the impulse, e.g. if it is negative or positive. Selye argued that stress differs from other physical responses in that it is identical whether the provoking impulse is positive or negative. He called negative stress “distress” and positive stress “eustress”. Negative stress would not allow a return to equilibrium, but would fuel the body’s state of distress caused by the stimuli. However, it is possible to change a negative stress into a positive or alarm stress: the body reacts to a stressor to which it is not adapted. Further, Selye described a system whereby the body copes with stress, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis system. Since the publication of his first scientific work in 1936, Selye has written more than 1700 works and 39 books on the subject of stress. To Selye’s most important works belong ‘The Stress of Life‘, published in 1956, ‘From Dream to Discovery: On Being a Scientist’ published in 1964 and ten years later ‘Stress without Distress‘. At the time of his death in 1982, his works were cited in more than 362 000 scientific works and in countless stories, in most languages and all countries. He is still by far the world’s most cited author on this subject.

Tabacco Controversy

In recent years it has emerged that Selye worked as a consultant for the tobacco industry from the 1950s until his death, receiving extensive funding for his research, and taking part in pro-smoking campaigns paid for by the tobacco industry.[4] He also helped R.J. Reynolds to recruit other scientists, and there is evidence that industry lawyers helped with the wording and content of some of Selye’s later academic papers.

Later Years

Selye held three doctorates (M.D., Ph.D., D.Sc.) and 43 honorary doctorates. He was a member of several dozen of the most prestigious medical and scientific associations, including a member of the Leopoldina since 1976. In 1975 he created the International Institute of Stress, and in 1979, Dr. Selye and Arthur Antille started the Hans Selye Foundation. Later Selye and eight Nobel laureates founded the Canadian Institute of Stress. Selye gained his international respect not only for his scientific achievements, but also through his dedication to the practical application of his work. Suffering from reticulosarcoma (a rapidly progressing cancer), he continued to work and develop his theory on stress, but finally died in 1982, at the age of 75. At the time of his death, his work had been cited in more than 362,000 scientific papers and in countless histories, in most languages and all countries. He is still by far the most cited author on the subject in the world.

Dr. Hans Selye, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Hans Selye at Britannica

- [2] Hans Selye Biography at Famous Scientists

- [3] Hans Selye at Wikidata

- [4] Petticrew, M. P.; Lee, K (2011). “The “father of stress” meets “big tobacco”: Hans Selye and the tobacco industry”. American Journal of Public Health. 101 (3): 411–418.

- [5] Hans Selye (1936) “A Syndrome Produced by Diverse Nocuous Agents” in Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences

- [6] Hans Selya, The Stress of Life. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1956,

- [7] Jackson, Mark (2014), Cantor, David; Ramsden, Edmund (eds.), “Evaluating the Role of Hans Selye in the Modern History of Stress”, Stress, Shock, and Adaptation in the Twentieth Century, Open Access Monographs and Book Chapters Funded by Wellcome Trust, University of Rochester Press

- [8] Hans Selye, “The General Adaptation Syndrome and the Diseases of Adaptation” (Part 1 / Part 2), Journal of Allergy [later and Clinical Immunology] 17/4 (July 1946): 231–247; and 17/6 (Nov. 1946): 358-98.

- [9] Dr. Hans Selye, cdnmedhall @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of Endicronologists, via Wikidata and DBpedia