View into the nave of Hagia Sophia from the gallery, photo: Andreas Wahra, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On May 7, 558, the main dome of Hagia Sophia, Church of the Holy Wisdom and seat of the Orthodox patriarch of Constantinople, collapsed completely during an earthquake. Hagia Sophia is one of the greatest surviving examples of Byzantine architecture. Emperor Justinian I himself had overseen the completion of the greatest cathedral ever built up to that time, and it was to remain the largest cathedral for 1,000 years up until the completion of the cathedral in Seville in Spain.

Build on the Foundations of a Pagan Temple

The first church on the site was known as the Megálē Ekklēsíā, the “Great Church”, build on the foundations of a pagan temple and inaugurated at 15 February 360 during the reign of emperor Constantius II next to the area of the imperial palace. It was claimed to be one of the world’s most outstanding monuments at the time. During the riots in the early 5th century following the second banishment of St. John Chrysostom, then patriarch of Constantinople, this first church was largely burned down and nothing remains of the first church today. A second church on the site was ordered by emperor Theodosius II and inaugurated in 415. However a fire started during the tumult of the Nika Revolt and burned it to the ground in 532. Only a few weeks later, emperor Justinian I decided to build a third and entirely different basilica, larger and more majestic than its predecessors. He chose physicist Isidore of Miletus and mathematician Anthemius of Tralles as architects.

Solomon, I have outdone thee!

Columns and other marbles were brought from all over the empire, throughout the Mediterranean. More than ten thousand people were employed. The emperor, together with the Patriarch Menas, inaugurated the new basilica on 27 December 537 – only 5 years and 10 months after construction start – with much pomp. Hagia Sophia was the seat of the Orthodox patriarch of Constantinople and a principal setting for Byzantine imperial ceremonies, such as coronations. Hagia Sophia is one of the greatest surviving examples of Byzantine architecture. Its interior is decorated with mosaics and marble pillars and coverings of great artistic value. The temple itself was so richly and artistically decorated that Justinian proclaimed, “Solomon, I have outdone thee!“

A Gigantic Structure

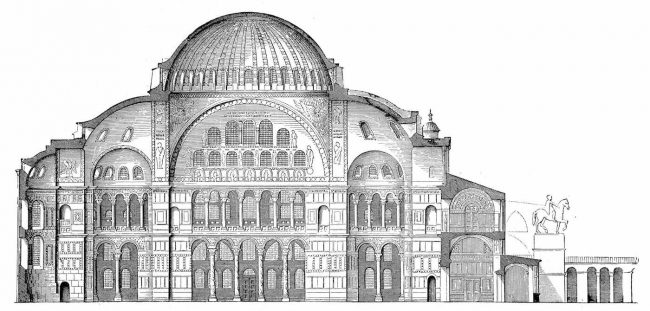

The vast interior has a complex structure. The nave is covered by a central dome which at its maximum is 55.6 m from floor level and rests on an arcade of 40 arched windows. Repairs to its structure have left the dome somewhat elliptical, with the diameter varying between 31.24 and 30.86 m. A hierarchy of dome-headed elements built up to create a vast oblong interior crowned by the central dome, with a clear span of 76.2 m. Interior surfaces are sheathed with polychrome marbles, green and white with purple porphyry, and gold mosaics. The dome of Hagia Sophia has spurred particular interest for many art historians, architects and engineers because of the innovative way the original architects envisioned it. The dome is carried on four spherical triangular pendentives, an element which was first fully realized in this building. Moreover, it was often interpreted by contemporary commentators as the dome of heaven itself. The structure has a total of 104 columns, 40 in the lower and 64 in the upper gallery.[3]

Cross section of the Hagia Sophia, Wilhelm Lübke / Max Semrau: Grundriß der Kunstgeschichte. 14. Auflage. Paul Neff Verlag, Esslingen, 1908

The Immense Weight and other Architectural Problems

The weight of the dome remained a problem for most of the building’s existence. Earthquakes in August 553 and on 14 December 557 caused cracks in the main dome and eastern half-dome. The main dome collapsed completely during a subsequent earthquake on 7 May 558, destroying the ambon, altar, and ciborium. The collapse was due mainly to the unfeasibly high bearing load and to the enormous shear load of the dome, which was too flat. These caused the deformation of the piers which sustained the dome. The emperor ordered an immediate restoration. He entrusted it to Isidorus the Younger, nephew of Isidore of Miletus, who used lighter materials and elevated the dome by about 6.25 meters – giving the building its current interior height of 55.6 meters. Moreover, Isidorus changed the dome type, erecting a ribbed dome with pendentives.

Earthquake and Repairs

In 726, the emperor Leo the Isaurian issued a series of edicts against the veneration of images, ordering the army to destroy all icons – ushering in the period of Byzantine iconoclasm. At that time, all religious pictures and statues were removed from the Hagia Sophia. After the great earthquake of 25 October 989, which collapsed the Western dome arch, Emperor Basil II asked for the Armenian architect Trdat, creator of the cathedrals of Ani and Argina, to direct the repairs. Upon the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade, the church was ransacked and desecrated by the Venetians and the Crusaders, as described by the Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates. During the Latin occupation of Constantinople (1204–1261) the church became a Roman Catholic cathedral. The Hagia Sophia was known to be in bad condition in 1261, when Eastern Rome took over the city again.[3] New cracks developed in the dome after the earthquake of October 1344, and several parts of the building collapsed on 19 May 1346.

Interior of the Ayasofya Mosque, a.k.a. the Hagia Sophia, from between 1900 and 1910, by the Ottoman photographic firm Sébah & Joaillier

When Constantinople Fell

Constantinople fell to the attacking Ottoman forces on the 29th of May in 1453. In accordance with the traditional custom at the time, Sultan Mehmet II allowed his troops and his entourage three full days of unbridled pillage and looting in the city shortly after it was captured. When Sultan Mehmet II and his accompanying entourage entered the church, he insisted that it should be converted into a mosque at once. One of the ulama present then climbed up the church’s pulpit and recited out the Muslin creed Shahada, thus marking the beginning of the gradual conversion of the church into a mosque. During the 16th and 17th century Ottoman period minarets on the exterior, a great chandelier, a mihrab, i.e. a niche indicating the direction of Mecca, a minbar, i.e. a pulpit, and disks bearing Islamic calligraphy, have been added to the mosque. In 1935, the first Turkish President and founder of the Republic of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, transformed the building into a museum.

The current Turkish government started to turn Hagia Sophia into a mosque again. On July 1, 2016, Muslim prayers were held again in the Hagia Sophia for the first time in 85 years.

Mehmet Ozalp, History and Symbolism of Hagia Sophia Public Lecture, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Hagia Sophia, Cathedral, Istambul, Turkey, at Britannica Online

- [2] Hagia Sophia, 532–37, at The Met Museum

- [3] Hagia Sophia Museum website

- [4] Hagia Sophia at Wikidata

- [5] New International Encyclopedia article about Hagia Sophia

- [6] Contemporary description of the Hagia Sophia by Procopius, Buildings (De Aedificiis), published in 561.

- [7] 360 degree panoramic view of the Hagia Sophia

- [8] Mehmet Ozalp, History and Symbolism of Hagia Sophia Public Lecture, ISRA Academy @ youtube

- [9] Emerson, William; van Nice, Robert L. (1950). “Hagia Sophia and the First Minaret Erected after the Conquest of Constantinople”. American Journal of Archaeology. 54 (1): 28–40.

- [10] Balfour, John Patrick Douglas (1972). Hagia Sophia. W.W. Norton & Company.

- [11] Gigapixel of Hagia Sophia Dome ( 214 Billion Pixel )

- [12] Timeline of Constantinople, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: 300-600: Constantine and Byzantium