Illustration of the Great Fire of London by an unknown painter

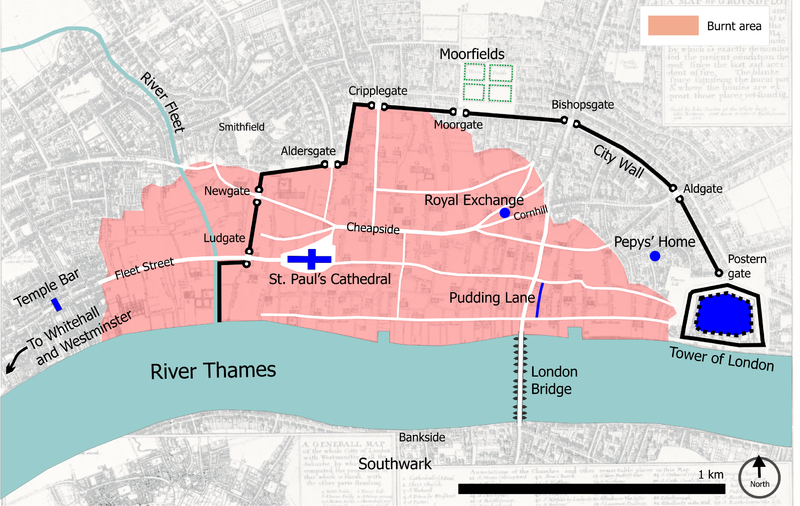

From Sunday, 2 September to Wednesday, 5 September 1666, a major conflagration swept through the central parts of the English city of London, destroying the medieval City of London inside the old Roman City Wall. The social and economic problems created by the disaster were overwhelming. Evacuation from London and resettlement elsewhere were strongly encouraged by Charles II, who feared a London rebellion among the dispossessed refugees. Despite numerous radical proposals, London was reconstructed on essentially the same street plan used before the fire.

London during the 17th Century

By the middle of the 17th century, London had become one of the largest cities in Europe and by far the largest in England. About half a million people lived crowded in wooden houses in a city that lived from trade with its busy harbor and numerous businesses. Fires were not rare back in these days since most buildings (except for those in the wealthy areas) were made of wood and as construction increased, the fire risks did as well. Pollution, the heat, open fireplaces, candles and sparks in the cities were just some of potential fire causes. The government tried to regulate the materials which were used for buildings to reduce the danger but was not listened to. Wealthy people preferred to live at a convenient distance from the traffic-clogged, polluted, unhealthy City, especially after it was hit by a devastating outbreak of bubonic plague in the Plague Year of 1665.

St. Paul’s Cathedral in Flames, by unknown painter

How the Great Fire Started

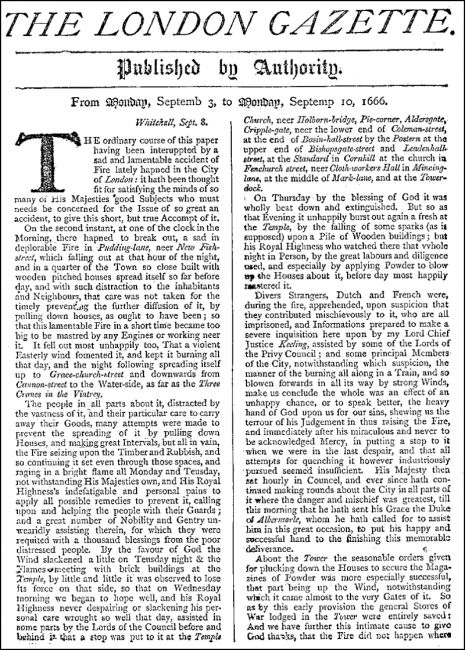

Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn were very important witnesses of the fire, writing down everything they experienced and the way they reacted to the events.[6,2] Before the fire, London experienced a long drought. In Pudding Lane, Thomas Farriner lived there along with his family, owing a small bakery business and on September 2, 1666 their house set fire. The family escaped but even with the help of the neighbors, the flames went on and on. When governmental officials arrived, they suggested to tear down the neighboring houses to decrease the risk of a wide spread, but it was too late. Soon, it reached the paper warehouses near the river and by Sunday morning several churches were destroyed along with 300 estimated civil houses. The people began leaving their houses, trying to catch boats on the river. The whole city developed the so called chimney effect, creating its own weather with increasing firestorms.

“Some of our maids sitting up late last night to get things ready against our feast today, Jane called up about three in the morning, to tell us of a great fire they saw in the City. So I rose, and slipped on my night-gown and went to her window, and thought it to be on the back side of Mark Lane at the farthest; but, being unused to such fires as followed, I thought it far enough off, and so went to bed again, and to sleep. . . . By and by Jane comes and tells me that she hears that above 300 houses have been burned down tonight by the fire we saw, and that it is now burning down all Fish Street, by London Bridge. So I made myself ready presently, and walked to the Tower; and there got up upon one of the high places, . . .and there I did see the houses at the end of the bridge all on fire, and an infinite great fire on this and the other side . . . of the bridge. . . .”

– Samuel Pepys‘ Diary, Sep 2, 1666

The Fire Continues

On the next day, the fire was still expanding up north and west. Towards the south, the river worked as a good shield but the houses on the London Bridge were destroyed. Towards the northern part, the financial district started burning, which resulted in panic in concerns of the melting gold coins. The Londoners became tired and exhausted, not knowing that this was only day 2 of 4. Also on that days, the public started to believe that the fire was not an accident and that more fires were set with purpose. The first targeted suspects were foreigners, and also the fear of a terrorist attack grew. The Lord Mayor left the city, even though he was responsible for coordinating the fire fighters. James, Duke of York then took charge and helped the people as much as he could, hiring firemen from the lower classes and setting up coordination posts. Still, the fire kept expanding and by the end of the day, the royal palace was completely in flames. It was rumored that even King Charles began working manually to help extinguishing the fire.

Map of central London in 1666, showing landmarks related to the Great Fire of London

Author: Bunchofgrapes

Evacuation

On Tuesday, demolition still increased. Even though the firefighters were able to create a firebreak, not even St. Paul’s Cathedral could be shielded. The people of London began taking all their good to the church, thinking they would be safe. But unfortunately, the young Christopher Wren [5] had the church covered in wooden scaffolding for restoration wherefore the roof began melting after half an hour when the fire reached it and the cathedral stood in flames. On Wednesday, the firebreaks finally took effect and the fire began to decrease. When it was finally put out, the city of London was left behind with numerous refugees and homeless, not knowing how to proceed. The prices for basic food, such as bread had at least doubled. Still, the fear for terrorists grew and the Londoners began to attack every foreigner they encountered. Fearing a rebellion in the demolished city, Charles II recommended the public to leave London.

The London Gazette for 3–10 September, facsimile front page with an account of the Great Fire.

The Destruction

The fire was reported to have destroyed almost 90 churches, over 13000 houses and numerous governmental buildings. The watchmaker Robert Hubert claimed to have started the fire as an agent to the Pope and was hanged for his confession. Unfortunately, it was later found out that he did not arrive in London two days after the fire started. Rebuilding began and several architects, including Christopher Wren sent in rebuilding plans for the city, but instead the old plan was realized with several improvements concerning hygiene and building materials.

“I did within these six days see smoke still remaining of the late fire in the City; and it is strange to think how to this very day I cannot sleep a-night without great terrors of fire; and this very night I could not sleep till almost 2 in the morning through thoughts of fire.”

– Samuel Pepys’ Diary, Feb 28, 1667

The Great Plague epidemic of 1665 is believed to have killed a sixth of London’s inhabitants, or 80,000 people, and it is sometimes suggested that the fire saved lives in the long run by burning down so much unsanitary housing with their rats and their fleas which transmitted the plague, as plague epidemics did not recur in London after the fire. However, historians disagree as to whether the fire played a part in preventing subsequent major outbreaks.

Laura Gowing, Arthur Burns, The Great Fire of London – what impact did it have on the city? [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Facing up to catastrophe: The Great Fire of London at Oxford University

- [2] Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn

- [3] James Leasor 1961, The Plague and the Fire

- [4] The Great Fire at the BBC

- [5] Christopher Wren and his Masterpiece – Saint Paul’s Cathedral, SciHi Blog

- [6] The Amazing Diary of Samuel Pepys, Esq., SciHi Blog

- [7] Rome is Burning, SciHi Blog

- [8] The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, SciHi Blog

- [9] John Snow – Tracing the Source of the London Cholera Outbreak, SciHi Blog

- [10] The Natural History Museum in London, SciHi Blog

- [11] The Great Fire at Wikidata

- [12] Laura Gowing, Arthur Burns, The Great Fire of London – what impact did it have on the city?, KingsCollegeLondon @ youtube

- [13] Tinniswood, Adrian (2003). By Permission of Heaven: The Story of the Great Fire of London. Jonathan Cape.

- [14] Images on the History of the City of London via DBpedia and Wikidata